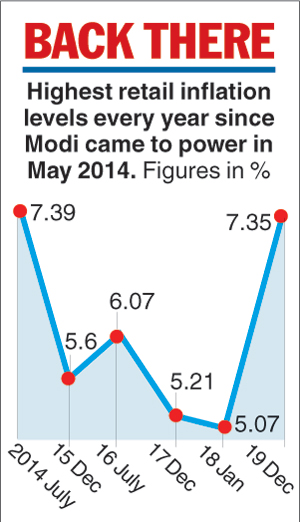

Retail inflation shot up to 7.35 per cent in December 2019 — the highest level in five years and five months.

This is the highest rate of inflation since July 2014 when it touched 7.39 per cent. Narendra Modi had first taken charge as Prime Minister in May 2014.

The big worry is that at this level, retail inflation is running way beyond the tolerance limit set for the Reserve Bank of India’s monetary policy committee (MPC).

In May 2016, the Reserve Bank of India was given a statutory mandate to cap inflation in the range of 2 to 6 per cent with the objective of keeping it as close as possible to a median rate of 4 per cent.

Retail inflation had come in at 5.54 per cent in November, setting off alarm bells on Mint Street as it had then risen to a 40-month high.

The highest level of inflation in the current series was in February 2013 when it spiralled upwards to 10.89 per cent.

The RBI — which held its hand on rate cuts at its December meeting after five successive interest rate reductions in 2019 — is almost certain to adduce its inflation-capping mandate to skip a rate cut once again when it meets next between February 4 and 6, just days after the Centre presents its budget.

That would be bad news for the Modi government which has been looking for a strong monetary policy response — read rate cuts — to complement its fiscal stimulus measures that it is expected to announce in the budget.

The surge in inflation — which has been triggered largely by a spike in vegetable prices by 60.5 per cent — has already kindled talk of stagflation in the economy.

Stagflation is a term used by economists to define an economy that has inflation, a slow or stagnant economic growth rate and a relatively high unemployment rate.

Inflation in pulses and products was recorded at 15.44 per cent while in the case of meat and fish, it was 9.57 per cent.

The Indian economy is projected to grow at 5 per cent this year — its slowest pace since the 3.1 per cent growth in 2008-09. Unemployment leapt to a four-decade high of 6.1 per cent according to the National Sample Survey Office’s study for 2017-18 that was released last May.

At a media conference exactly a month ago, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman was asked for her comment after some experts started talking about an incipient stagflation-like situation at a time when factory output had shrunk in the past three months and inflation had soared to a 40-month high.

The finance minister had tersely replied: “No comments. Stagflation is a narrative that is going on. I am hearing it.”

Not everybody believes that this is anywhere near a stagflation-like situation.

“It may be an over-exaggeration to call India in stagflation (after all, growth is still above 4 per cent),” says Nikhil Gupta, chief economist, Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

“But the debate over rate hikes may get serious,” he says after flagging a short note that carries an ominous header: “Forget about rate cuts, can rates be hiked now?”

M. Govinda Rao, chief economic adviser, Brickwork Ratings, and former member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council and member of the 14th Finance Commission, says: “With the CPI inflation breaching the RBI’s target of 6 per cent for the first time in the last 41 months, there is little scope for the MPC to continue with monetary policy easing at least in the short term.”

Some economists believe that inflation will taper down to 6 per cent in the next few months after the new crop arrives and food inflation starts to cool.

“Vegetable prices and inflation should come down in January when the new onion crop comes in and prices move down. However, the low base effect will impact inflation for one more month,” said Madan Sabnavis, chief economist, Care Ratings.

Core inflation — which strips out the effects of food and energy — rose to 3.7 per cent in December, driven by a railway freight rate rise.