When Narinder S. Kapany was in high school in the 1940s in Dehradun, his science teacher told him that light travels only in straight lines. By then he had already spent years playing around with a box camera, and he knew that light could at least be turned in different directions, through lenses and prisms. Something about the teacher’s attitude, he later said, made him want to go further, to prove him wrong by figuring out how to actually bend light.

By the time he entered graduate school at Imperial College London in 1952, he realised he wasn’t alone. For decades researchers across Europe had been studying ways to transmit light through flexible glass fibres.

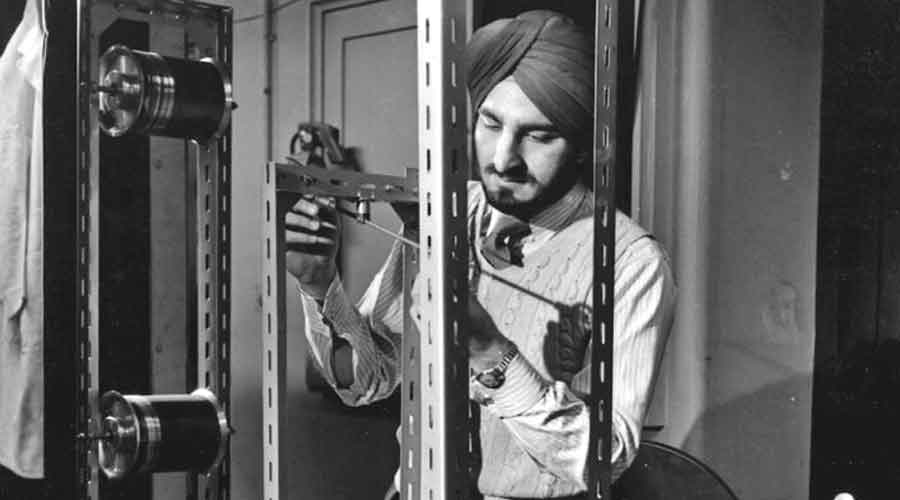

He persuaded one of those scientists, Harold Hopkins, to hire him as a research assistant, and the two clicked. Professor Hopkins, a formidable theoretician, provided the ideas; Kapany, more technically minded, figured out the practical side. In 1954 the pair announced a breakthrough in the journal Nature, demonstrating how to bundle thousands of impossibly thin glass fibres together and then connect them end to end.

Their paper, along with a separate article by another author in the same issue, marked the birth of fibre optics, the now-ubiquitous communications technology that carries phone calls, television shows and billions of cat memes around the world every day.

In later years, journalists took to calling Kapany the “father of fibre optics,” and several even claimed that he had been robbed of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics, which instead went to Charles Kao for his own groundbreaking work in fibre optics.

That claim re-emerged after Kapany died on December 3 in Redwood City, California, at 94.

Whether Kapany’s scientific contributions stand alongside Kao’s is debatable, but his work as an intellectual evangelist for the burgeoning field of fibre optics is undeniable.

“He was a pioneer,” the science journalist Jeff Hecht said in an interview, an “enthusiastic promoter” of a technology that long seemed more like science fiction than fact.

According to Hecht’s 1999 history of fibre optics, City of Light, between 1955, when Kapany received his doctorate, and 1965, he was the lead author or co-author of 56 scientific papers, an astounding 30 per cent of all research published in the field during that decade. He wrote the first book on fibre optics and, in a 1960 cover article he wrote for Scientific American, even coined the term itself.

Narinder Singh Kapany was born on October 31, 1926, in Moga, a town in Punjab, and raised in Dehradun. His father, Sundar Singh Kapany, worked in the coal industry; his mother, Kundan Kaur Kapany, was a homemaker.

After graduating from Agra University, he worked for a government munitions factory in Dehradun before moving to England.

Kapany had originally moved to Britain for an internship at an optics firm in Scotland, to learn skills he could use in starting his own company back in India. But the opportunity to work with Professor Hopkins, a towering figure in the world of optics, was too tempting to resist.

However, their relationship, though fruitful, proved unstable: Both of them were men with outsize personalities, and they fell out soon after publishing their seminal paper in Nature.

In 1954, soon after the Nature article appeared, Kapany married Satinder Kaur, who was studying dance in London. The next year the two sailed to New York after he was offered a job at the University of Rochester and a consulting contract with Bausch & Lomb, the eye care company.

Two years later, after the birth of their son, Raj, the Kapanys moved to Illinois, where Kapany took a job teaching at the Illinois Institute of Technology and where their daughter, Kiran, was born.

But Kapany was growing restless in academia, and in 1960 he moved his family to California to start a new company, Optics Technology, to commercialise his research. He based it in Palo Alto, then just emerging as a tech hub, and received funding from Draper, Gaither & Anderson, one of the first venture-capital firms on the West Coast.

Kapany took the company public in 1967. He left that same year and, in 1973, founded a new company, Kaptron, which made fibre optics equipment. He founded yet another company, K2 Optronics, in 1999. But Kapany never fully left academia: He taught at the University of California, Santa Cruz, from 1977 to 1983, and he later endowed chairs at several University of California schools in optics and in Sikh studies.

Kapany was a practising Sikh and fiercely proud of his heritage. He amassed one of the world’s largest collections of Sikh art and sponsored rooms to feature it in museums.

“My father became convinced that the world at large should know who the Sikhs are and the Sikh people themselves should not forget who they are as they emigrate to other lands far from their original roots,” his daughter said.

But he was also aware of how exotic he seemed to some as an Indian in early post-war America. Whenever he demonstrated fibre optics to visitors, he called it his “Indian optical rope trick”.

And he adopted an American accent, retaining just enough of his Indian and English tenor to make him stand out.

“He used that turban like a lethal weapon,” his son said. “When you see a guy who looked like that and who spoke like JFK, you’re not going to forget him.”

New York Times News Service