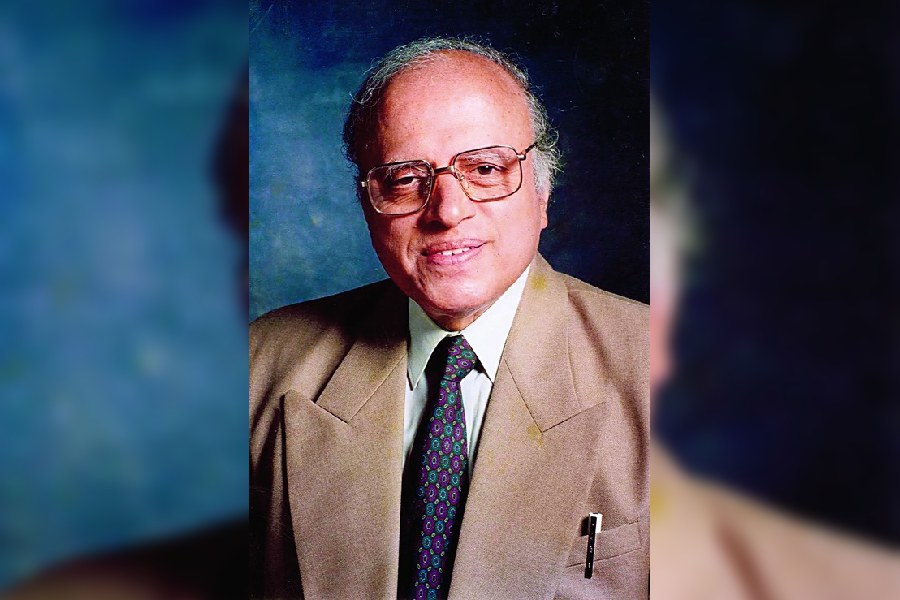

M.S. Swaminathan, the architect of the Green Revolution who steered India out of the era of famines, advocated agriculture focused on resource-poor farmers, and crusaded for conservation, even inspiring a “Noah’s ark” for the world’s plants, died on Thursday. He was 98.

“With profound sadness, we convey that our founder professor M.S. Swaminathan passed away this morning at 11.15am at his residence in Chennai,” the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), an institution he had founded in 1988, said.

Crop scientists have described Mankombu Sambasivan Swaminathan as among the most influential Asian scientists of the 20th century, whose ideas have continued to guide research efforts to address lingering and emerging challenges — from under-nutrition to environmental degradation and global warming.

Senior scientist P.C. Kesavan, who studied under Swaminathan, sees a link between the Bengal famine in 1942-43 and Swaminathan's work two decades later. After Independence, Kesavan wrote in a paper on Swaminathan in 2014, the first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru's declaration that "everything else can wait, but not agriculture" served as a "clarion call" to Swaminathan.

On Thursday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi posted on X: “At a very critical period in our nation’s history, his groundbreaking work in agriculture transformed the lives of millions and ensured food security for our nation.”

Swaminathan, who specialised in finding ways to optimise crop productivity in the early 1960s, had told the Indian government to invite US crop scientist Norman Borlaug and apply some of his ideas to develop high-yielding wheat varieties in India.

Famines and food shortages across India during the 1960s had compelled the country to depend on foreign food aid brought by ships, something Swaminathan agonised about, once describing those circumstances as a “ship-to-mouth existence”.

Crop scientists in India who applied Borlaug’s ideas to rice and wheat watched grain production soar. Wheat yields increased from 800kg per hectare in the 1960s to over 2,800kg per hectare by the early 2000s. Rice yields showed similar gains.

But Swaminathan was among the first to recognise and caution against the potential risks of relying exclusively on the Green Revolution.

“His contributions were unparalleled,” Kailash Chander Bansal, former director of the National Bureau for Plant Genome Resources, New Delhi, said.

“Although he spearheaded the Green Revolution, he also underlined concerns about the excessive use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides that the Green Revolution demanded.”

Swaminathan conceived an alternative — something he called “an ‘evergreen revolution’”.

The evergreen revolution, according to Bansal and others, focused on sustainable farming and plant varieties, including indigenous, native varieties that would be more attractive to resource-poor farmers in India and other developing countries than varieties that demand excessive inputs.

“In an era of climate change, the rising cost of chemical fertilisers, and energy requirements for farm operations, the evergreen revolution is the best available option for hundreds of millions of resource-poor small and marginal farmers,” crop scientists Kesavan and R.D. Iyer wrote in 2014, outlining Swaminathan’s contributions in a paper in the journal Current Science.

Swaminathan advocated the application of genetic engineering for crop improvement. At the MSSRF itself, scientists have introduced salt-tolerance genes from a mangrove plant species into a cultivated rice variety, hoping to engineer rice tolerant to salt-laden soils.

But Swaminathan also emphasised that the environmental and health safety aspects of genetically engineered crops needed to be rigorously evaluated and that any crop not known to be absolutely safe should not be introduced into the environment, Kesavan and Iyer wrote.

His suggestions for what he hoped would be a “zero hunger” world included expanding the basket of cultivated crops — promoting alternative cereals such as millets and nutrient-rich crops such as drumstick, citruses and breadfruit, among others.

Swaminathan, speaking at an international genetic conference in New Delhi in 1983, had called for an international effort to create a bank of seeds representing the world’s plants, underlining the need to preserve biodiversity for future generations.

In 2008, the Norwegian government opened the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a repository of seeds of more than a million plant varieties from across the world, preserved at low temperatures. The facility is intended to serve as a safeguard against the permanent loss of seeds elsewhere from natural disasters or other factors.

“We view Swaminathan’s call in 1983 as among the contributions leading to the creation of the seed vault,” Kesavan, a plant geneticist and radiation biology specialist, told The Telegraph on Thursday. “The vault serves like Noah’s ark, a safety net for food security under climate change.”

Rajeev Varshney, a plant genome scientist at Murdoch University, Australia, who says Swaminathan was a mentor and guide to him for over 25 years, sequenced Swaminathan’s genome and presented it to him on his 90th birthday on August 7, 2015. “We requested him, he was happy to give us a blood sample... it was to understand the genome of a person known for his energy, brilliance and hard work.”