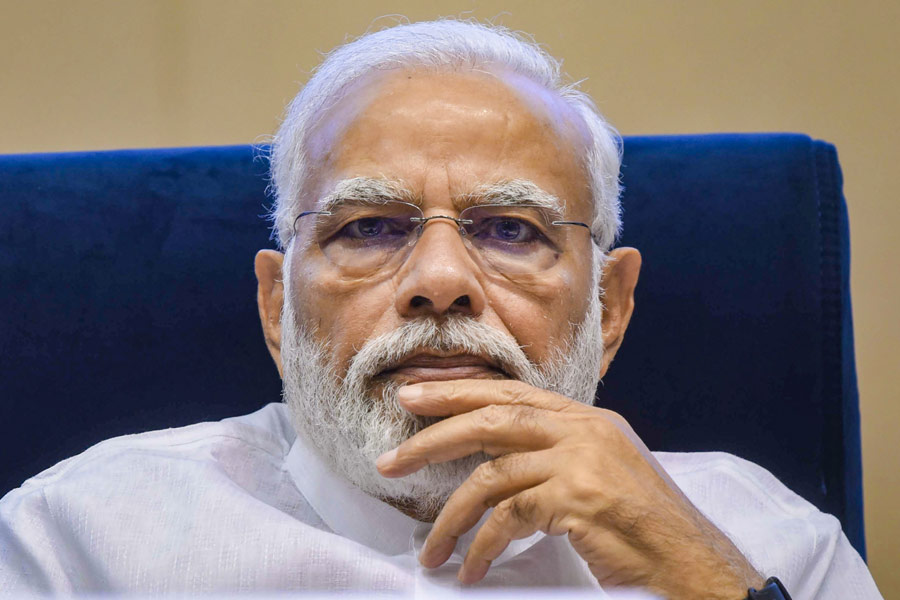

One hundred days ago, Narendra Modi was the badshah of all he surveyed and more. Eclipsing his party’s most optimistic predictions, the BJP had picked up more seats than in 2014 and Modi had vanquished all foes.

Rahul Gandhi resigned his office and the elders in the Opposition, in the hunt for the proverbial ghosts in the machine, concluded the EVMs were rigged. Could anything now possibly go wrong?

The answer after 100 days into Modi 2.0 is plenty. For starters, the Indian economy’s gone pear-shaped at remarkable speed with growth sinking to a six-year low. Wrestling the economy back into shape may turn out to be the most formidable challenge Modi’s faced since first taking office in 2014.

The flood of bad economic news began with the dramatic slamming of brakes in the automobiles, trucks and two-wheeler sector. Then came even more ominous signs that the economy was in sad shape when people slowed down on buying low-cost items like toothpaste, soap and even biscuits. Suddenly, news headlines were full of talk about job losses that were impacting all the way to the village level as laid-off workers returned home facing a grim future.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. From Day One, the message was Modi 2.0 was a government in a hurry and would get things done. Information & broadcasting Minister Prakash Javadekar summed up the strategy as: “speed, skill and scale”. Bills were slammed through Parliament on everything from triple talaq to setting up a National Sports Education Board. The Opposition was reduced to grumbling they were sitting extra time and that none of the bills was being referred to parliamentary standing committees. Modi even put a figure on his ambitions. India, he told a chief ministers’ gathering,,would be a $5-trillion economy by 2024 when the next elections are due.

Soon, though, it became clear that Modi’s rosy hopes for the future were premature. Confirmation the economy was in deep trouble came when the first quarter (April-June) GDP figures showed growth had tumbled to 5 per cent. What’s more, a recovery looks unlikely in the next few quarters. Says a senior economic analyst: “Everyone’s stuck in the mindset there’ll be a ‘return to the mean’ and that 7 per cent growth is our entitlement and will return. It won’t for some time.” (Incidentally, according to the Economic Survey, India will need 8 per cent annual growth to become a $5-trillion economy).

As the bad tidings accumulated, suddenly, Modi’s golden touch seemed to become more elusive. In August, GST collections fell to Rs 98 lakh crore, which was less than the July figures. More importantly, the government needs monthly collections of well over Rs 1 lakh crore to balance its books. And after all the election hype of India being the world’s fastest-growing economy, with consumption, investment and exports all sluggish, the country’s lost that title to China where growth was 6.2 per cent in the most recent quarter.

The first sign the government was mishandling the situation came when finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the revised budget which hit all the wrong notes with the business community. They were horrified by the 7 per cent tax surcharge on salaries of over Rs 5 crore. Even worse, the supposedly business-friendly government was threatening to turn non-fulfilment of corporate social responsibility into a criminal offence. The tragic suicide of V.G. Siddhartha, the Café Coffee Day founder who was in financial difficulties but also had disputes with the Indian Revenue Service, stoked the anger of India Inc which started talking about “tax terrorism”.

With unemployment at a 45-year high and consumer demand low – passenger-car sales plummeted 30 per cent in August and construction and real estate are struggling badly -- there’s an urgent need to get the economy back on its feet. But with the government targeting a fiscal deficit of 3.3 per cent of GDP, room to implement counter-cyclical measures is limited.

Sitharaman announced a post-budget recovery package. But the main feature was removal of a tax on earnings for foreign portfolio investors which had been one of the more unpopular features of her recent budget. She also backed off from another big idea in the budget -- to treat not achieving CSR targets as a crime.

Sitharaman’s second relief package failed to raise “animal spirits” either with markets disappointed to find it was only about bank mergers, which one commentator dismissed as an idea whose time had long gone. Publicly, top bank managers praised the move to merge 27 public-sector banks into 10, but privately they were scathing. It seems a chief criterion used for pairing off the banks was common software. So one bank using Infosys’ Finacle software was slammed together with another bank also using Finacle.

In the meantime, the Opposition’s in deep disarray with some commentators gloomily concluding Congress’s potential demise as a significant political force could leave India as a one-party state. Rahul Gandhi’s quit as party president to be replaced by his mother Sonia. The government has put former finance minister P. Chidamabaram in Delhi’s Tihar jail, while he answers questions about alleged financial corruption. It’s murmured Chidambaram’s imprisonment could be a tit-for-tat for when Shah was jailed on murder charges by the Congress government over a fake-encounter (Shah was acquitted). And Modi’s lost his consensus-builder and the man seen as the BJP’s liberal face, Arun Jaitley, to cancer. About the only feel-good news has been Olympic silver medallist P.V. Sindhu becoming India’s first badminton world champion.

What’s next? The last election appears to have convinced Modi that welfare schemes collect more votes than promises of Make in India or achchhe din for businessmen. The Saubhagya electrification scheme, greater availability of gas cylinders and even the building of rural toilets are what reaped the most support, according to senior government members and Opposition leaders. There’ve been questions about the numbers involved in all these schemes but there’s no doubt they show that Modi’s strong on execution. He sets a target and actively pushes for it to happen.

It’s tough to forecast which way the government will proceed on the economy. Modi’s always preferred a command economy situation where he tells people where to invest. He’s never run a belt-tightening government. The Reserve Bank of India this year is dipping into its rainy-day contingency fund and transferring a record Rs 1.76 lakh crore to the government to cover its revenue gap and help it crank up growth. But Modi can’t count on such largesse forever.

The BJP manifesto promised to spend Rs 100 lakh crore on infrastructure by 2024 and that farmers’ incomes would double by 2022. As Modi firmly believes rolling out mega-schemes brought him back to the top job, he isn’t going to welcome a regime in which saving money might have to get more priority than spending. But he may have no other option. Incidentally, this situation has arisen once before.

Following the 1971 war, Mrs Indira Gandhi’s top advisors – even the more Left-leaning – advised her the time for thrift had come. She ignored them with devastating consequences. Does history always repeat itself?

As well, on the government’s plate is the Kashmir bolt from the blue. The government began pouring troops into the Kashmir Valley. Simultaneously, it denied it had any intention of abolishing Article 370 or Article 35A but then went and did exactly that. Only time will tell whether it’s overestimated its ability to control the situation. But after one month, mobile and Internet connections are still down though the government insists 80 per cent of landlines are functioning. The government’s determined to keep Kashmir’s established parties out of the political mix, but its plan for promoting panchayati raj leaders is questionable. This week, Amit Shah met panchayati raj leaders and declared one of them would be the future chief minister. The panchayat leaders may have welcomed the new career opportunities, but for now, many are scared to return their homes.

And if Kashmir on the boil isn’t enough, the government’s also in a fix in Assam where almost nobody’s happy after the National Register of Citizens survey showed 1.9 million people to be possible non-citizens. These non-citizens now have four months to file appeals but the BJP’s calling for a recount after more Hindus showed up on the list than Muslims.

One campaign promise, though, that might indeed be met is a resolution of the Ram Temple imbroglio. A five-judge Supreme Court bench is hearing the case. Of course, a ruling could cause more unrest.

Modi always asked for 10 years from voters to finish the task of transforming India and taking it into a new Golden Era. Now he’s got it. What’s more, this time, with 300 seats, the BJP can safely show a finger to its allies. Equally important, this time Modi and his home minister, Shah, are no longer novices in the capital. They know where the levers of power are located in Delhi and how to tug on them for best effect.

So far, even with the economy tanking and agrarian distress, Modi and his “Modinomics” are still riding high in voter popularity. Even Opposition leaders such as MIT-trained Congress veteran Jairam Ramesh have offered him qualified support, urging Indians to “recognise Prime Minister Modi’s good work and what he did between 2014 and 2019 due to which he was voted back to power by over 30 per cent of the electorate.”

But while at 50 days the government was looking sure-footed even if its critics didn’t like many of its moves, at 100 days it’s starting to look like an administration relying on ad-hoc measures to see it through. India still has another 1,720 days to go under Modi until the 2024 elections. There’s no denying these are difficult times but the Prime Minister has enormous voter charisma and cannot be underestimated. Barring a massive upheaval in the political landscape, it looks like “Modi will remain India” for the foreseeable future, one Opposition figure commented.