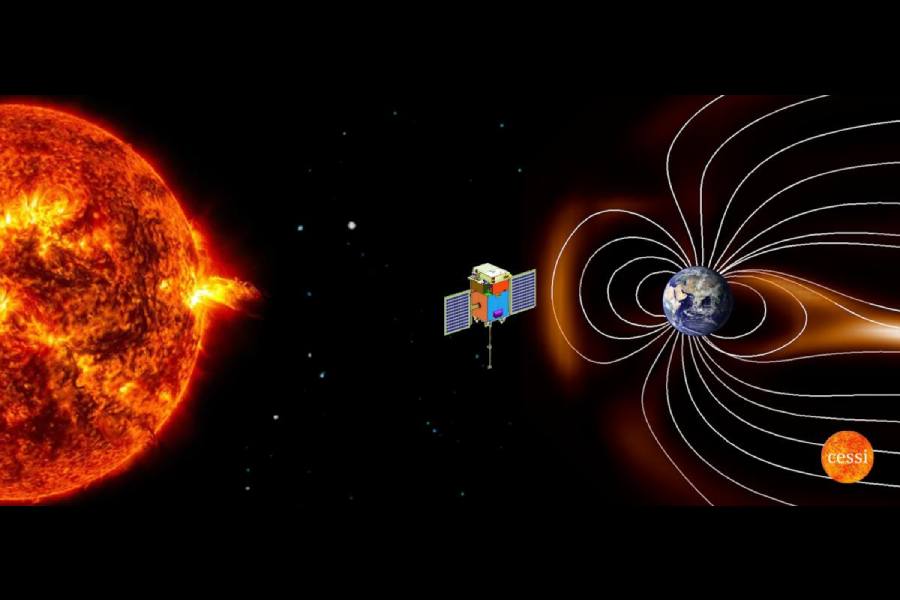

India’s first space-based observatory for uninterrupted studies of the Sun executed crucial orbital manoeuvres on Saturday and slipped into its intended vantage outpost around a point called L1, hitherto occupied by only European and US spacecraft.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) said the Aditya-L1 spacecraft, launched on September 2, had successfully reached its halo orbit, located roughly 1.5 million kilometres from the Earth, after onboard thruster rocket firings at about 4pm IST on Saturday.

Aditya-L1 has seven scientific instruments — four to observe the Sun and three to measure the impacts of solar activity in the vicinity of the spacecraft’s halo orbit. They are expected to provide fresh insights into solar mechanisms and help generate space weather alerts triggered by activity such as solar storms, solar flares, and mass ejections from the corona.

“This is a major milestone for the Indian space programme,” said Dipankar Banerjee, an astrophysicist and director of the Aryabhatta Research Institute for Observational Sciences, Nainital, who was one of the scientists who had proposed an Indian space-based solar observatory over 15 years ago. “Placing the spacecraft into the L1 halo orbit is a tricky task,” Banerjee told The Telegraph on Saturday.

Only the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) and the European Space Agency (ESA) have sent spacecraft to the L1 point — Nasa’s Wind spacecraft was launched in 1994, the Nasa-ESA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory in 1995, and Nasa’s Advanced Composition Explorer in 1997.

Aditya-L1’s planned lifespan for observations is at least five years.

The insertion of Aditya-L1 into the halo orbit demanded precise navigation and control, Isro said in a statement. The successful insertion signals Isro’s capabilities for such complex orbital manoeuvres and bolsters confidence for future interplanetary missions, it said.

“Getting the speeding spacecraft into the halo orbit required reducing its speed and changing direction by firing its onboard thrusters,” said Dibyendu Nandi, a solar physicist at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Calcutta.

“It is like exiting a high-speed expressway and moving into a side road to access the suburb around L1. And doing it well implies lower fuel consumption and therefore longer mission life,” said Nandi, who had chaired a scientific panel on how Aditya-L1 could be used for space weather studies.

The Sun-observing instruments on Aditya-L1 are intended to study solar storms and solar flares, and probe a longstanding mystery about the solar corona: why is the corona — the Sun’s atmosphere — a million degrees Celsius, much hotter than the solar surface which is 6,000°C.

The instruments studying the impacts of solar activity in the vicinity of the L1 point could be used to generate space weather alerts — possible adverse events such as massive bursts of subatomic particles triggered by solar magnetic storms that might have the potential to disrupt satellites’ operations.

Depending on the power and the direction of such solar ejections, Nandi said, an alert flagged by Aditya-L1 could provide up to 30 minutes’ advance warning about impacts near Earth. Such events have the potential to damage satellites in orbit around Earth. A few minutes’ advance notice might be sufficient time for space agencies to take evasive action such as switching off critical systems.