Last Sunday, the human debris of battle in Kashmir threw up a trophy and an oddity. A battery of militants holed up in Zainpora in south Kashmir’s Shopian was blown. Saddam Padder, once comrade-in-arms to Burhan Wani and himself among the most wanted, finally lay dead. Beside him, among four others, was one Rafi Bhat, assistant professorof Sociology at the Kashmir University (KU). Padder had served insurgency a fair few years; Bhat had been in the runaway lane no more than 30 hours. Upon finishing work the previous Friday, he had called his mother in Chhunduna, a village some 25 kilometres north of the KU campus, to ask if she required anything from town; he was done for the day and heading home. Then, his mobile logged off the networks. Bhat was gone. Someone later told his parents they had last seen him getting into a white car and being driven off. He returned in a hearse.

Nothing here that surprises or shocks anymore; this has begun to be the story of more and more homes in Kashmir. Boys leave, and it’s as if they have taken a home wall along; there’s nothing to do but for the rest to gape the void. Nobody knows, nobody ever has a clue that a sudden departure impends the family. These are homes tunnelled under --- wires have been laid and lines opened, subterranean networks built, subsonic conversations established. Somewhere in a darkened bedroom, a sleeper cell not asleep. A laptop humming, an incandescent smartphone --- connection, inspiration, indoctrination, induction, command. One day, it’s suddenly time to push that button, Submit! Go! Gone. From countless homes. Nobody knows who next, but the sense and the inevitability of it is pervasive: boys will go, this boy or that.

This is a target-rich environment, oozing a toxic alchemy of anger, indignation, frustration, alienation, aspiration. It’s sore all over, it gives to the touch; wound begets wound until it begins to hurt no more. Earlier they’d flee to safety at the first whiff of a security column headed towards them. Now, more and more, the vogue is to head into it, besiege it, disrupt it, disable it, without care for consequences. What the Kashmiri mob does, collectively, openly, vociferously, and what Kashmiri boys do, individually, surreptitiously, quietly, are spurred by the same sense --- no fear of consequences, and very often, the acceptance of death, the willingness to perish. “It’s changing radically,” a minister in the Mehbooba Mufti government says, himself palpably shaken by the pace of change, “It is as if they are not afraid to embrace death, all of them.” The street is thick with ready recruits; the market is competitive. You could be wrong to think it’s only the Jaish-e-Mohammed or the Lashkar-i-Toiba or the Hizbul Mujahedin out in the bazaar, hiring. Or that the motivation is all Pakistan driven. Kashmir is becoming the theatre, albeit small yet and peripheral, of aspirations and objectives that leap far beyond the subcontinent. Consider this excerpt from a report filed for the West Point Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) earlier this year:

“The presence of Islamic State in J&K (ISJK) progressed gradually during 2017, starting with reports of Islamic State flags being waved during rallies and protests around the valley. While this claim is still pending official verification, Islamic State’s Amaq news agency claimed responsibility for an attack in Srinagar on November 17, 2017, which killed an Indian policeman. The militant killed in the attack, Mugees Ahmed Mir, is suspected to have been inspired by the Islamic State’s online propaganda and was found wearing an Islamic State T-shirt at the time of the attack. For the most part, though, signs of ISJK’s existence have largely been observed in the online realm alone. Since late 2017, the pro-Islamic State J&K-focused media group Al-Qaraar has engaged in a social media campaign, directing messages tailored to inspire a Kashmiri audience. In December 2017, a pro-Islamic State video in Urdu was shared via its Telegram channel, using the hashtag 'Wilayat Kashmir', in which a masked man representing 'Mijahididin in Kashmir' pledges allegiance to the Islamic State and specifically invites the al-Qa`ida-affiliated group Ansar Ghazwat-ul-Hind to join the caliphate.

“Although videos and pictures are a part of ISJK’s online effort, more substantive materials have also been produced. The more detailed writings distributed by Al-Qaraar entitled 'Realities of Jihad in Kashmir and Role of Pakistani Agencies' and 'Apostasy of Syed Ali Shah Gheelani and others' provide deeper insights into the nature of the jihad that the Islamic State seeks to promote amongst Kashmiri followers…. ISJK’s message may be more appealing to its target audience given its reputation as a newer, younger, and perhaps a more aggressive entity as well as its skillfulness at using online platforms….”

Among the militants at large in Kashmir today is Zakir Musa, who signed up with the Al Qaeda last year, debunked the Kashmiri cry for “aazaadi” as minor and declared the Hurriyat heretics to the cause he had embraced. Musa remains famously at large (he mostly likely operates out of locations in Tral in south Kashmir) and he isn’t without those that swear by him and his manifesto, which, like the JKIS project, is broader than the purposes of Pakistan or Kashmir-based armed outfits. Eisa Fazili was one such.

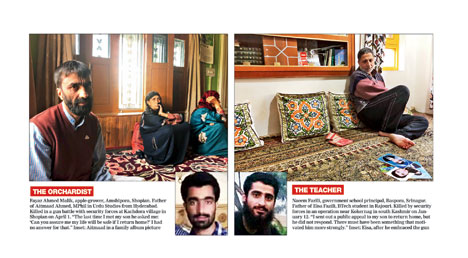

Baspora, on the northern fringes of Srinagar. A suburban settlement at a remove from the clutter of midtown neighbourhoods. Down an alley off which several run off, like tributaries, an unwrought gate and beyond it an airy acreage festooned with April blossom; nothing coaxes flowers like seasons, nothing kills them like seasons. The Fazili brothers live together-apart --- separate homes that open upon a central space that awaits landscaping. A child tossing a shuttle off her racket. An elderly woman stooped on steps in a far corner, lost in herself, unfazed by arrivals that dog barks have announced. In an oblong room on the floor level in one of those homes, is the Fazili we have come looking for: Naeem. Stubbled, reticent, still a little stunned. “We had no idea where Eisa was headed, he gave us no clue. He was a quiet boy, he’d argue sometimes, but he was a proper boy, well-behaved, studious; he’d listen, he kept in touch. Then suddenly he vanished one day and we never got him back. We’ve been through a lot, I don’t want to repeat all of it because it is painful over and over again, but we’ve been through terrible things, my wife, our whole family. When I finally learnt, alerted to an online post by a friend, that my son had taken up the gun, there was shock. I could not understand why. But I can now look back to clues we did not pick up. He was terribly upset once to see a student being gunned down by security forces. That evening he came and asked me, rather angrily, what the purpose at all was of studying if students were to be killed like that, randomly, in the middle of the street. On another occasion he had put up pictures of bodies charred in a security operation, horrid pictures. I admonished him and he took them down, but perhaps all this was working on him. He was upset, although he seldom spoke about these things. I still have problems believing what he decided to do, that he is no more among us. I tried to locate him, but without success. I published an appeal to him in the newspapers. I tried to reason with him, publicly, but he never got back once he left. Perhaps he was motivated by stronger things. You see, the thing is, the way it is and has been in Kashmir, we have been robbed of reasoning with our children, telling them what to do what not to do. They see injustice and violence all the time, they have grown up in bloodshed and suppression. Nowadays, they have all the means to keep up with what is happening and why. Nothing can be hidden from them. They draw their own conclusions, they are in touch with others, they take all of this in. They react. We are speechless, we do not know what to tell them, we do not know how to stop them, we do not even know they have decided to go away.”

Amshipora. A scoop of fragrant earth in Shopian, 60 kilometres zig-zag south of Srinagar, down a road often advised against because it is a rogue road --- mines, ambushes, hostage-taking, gunfire, explosions, hit-and-run raids, sudden death. That’s quotidian; happens. But enough else happens. Extraordinarily. A frothy torrent of spring. A coppice ringing with birdcall. A roadblock caused by wool on hoof --- the most lustrous mountain-goats you’d see. Looming, wallpaper unreal, the Pir Panjal, freshly talcumed in snow. This patch is voluptuous with the promise of plenty in its orchards, overrun with heartbreak in its hearths. Shopian is the paradisal capital of blood-stains, and Amshipora is a recent clot. Over the last few years, Shopian is where The apple-yards are abuzz, the homes sullen, silent. Fayaz Malik, father of Aitmaad, has heard of our having knocked at his door and been shown in by the women of the house; the men are all out at work. He arrives, presently, a reedy man with a straight gaze and strong workman’s palms. His handshake is firm, affirming. He would say little beyond the pleasantries. His wife and sister join him; they’ve brought in glasses of cool fruit pulp but they squat at an implacable distance, as if to say all they want is to listen. “I wish I could tell you why my son went away, but perhaps I already know. Everybody knows, you know. Look at the state of the place. There isn’t a branch in Kashmir left untouched by this ruinous gust. It has taken my son away. And many more will follow. The way we have become, I think we are not affected by loss anymore. One day we lose a child, the next we are working in our orchards. We are not afraid to die, it appears. Itis the way of things. It is the way we have turned. No regrets, but who wants to lose a son. He was a studious boy, he was keen on studying on and securing a PhD in Urdu. But I don’t know what else he was reading, he was always reading. He was probably reading religious texts. He gave us no idea what was going on in his mind, who he was in touch with. He was like a brother to me. I did try to bring him back. But you know I did not succeed. The last time I met him it was in the middle of an orchard. It was twilight, almost dark. There were eight or ten men with him, armed men. But only my son and a friend approached me. We embraced. I tried to reason with him, come back I pleaded. He asked me: Abba, can you assure me that if I come home I will not be killed some day? I had no answer to that, none that hewould believe anyway, none that I would myself believe. We want our rights, our freedom, it is our haq, yeh haq ki ladai hai aur isme koi compromise nahin. How many will they kill? Do you know how many are prepared to die? The day my son was killed, and it was a horrible day because 20 people died that day in this neighbourhood, many boys vanished from their homes. We all know where they have gone and for what. Perhaps they will all end up like my son, they know it, but they still went. More will go. Do you know what our Prophet said when he was asked what is the meaning of qayamat, doomday? He said when a father has to haul his son’s coffin onto his shoulders, that is qayamat. What else may I tell you?”