Kintu, revolutionary Bhagat Singh was an atheist. After a thorough examination of his self, he rejected god, and therefore religion, so that nothing came between him and freedom. He also saw the collusion of the state and religion.

This is a useful thing to remember in the times of Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav, when his portrait, hatted, moustachioed and wearing a collared shirt, has been easily appropriated into the Hindu nationalist iconography. In Bollywood films, he is seen making jingoistic speeches.

A few months ago Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid a long, full tribute to him, dripping adulation. It may also be remembered that Singh’s popular portrait shows him in disguise, when he was escaping the British. He could look very different otherwise.

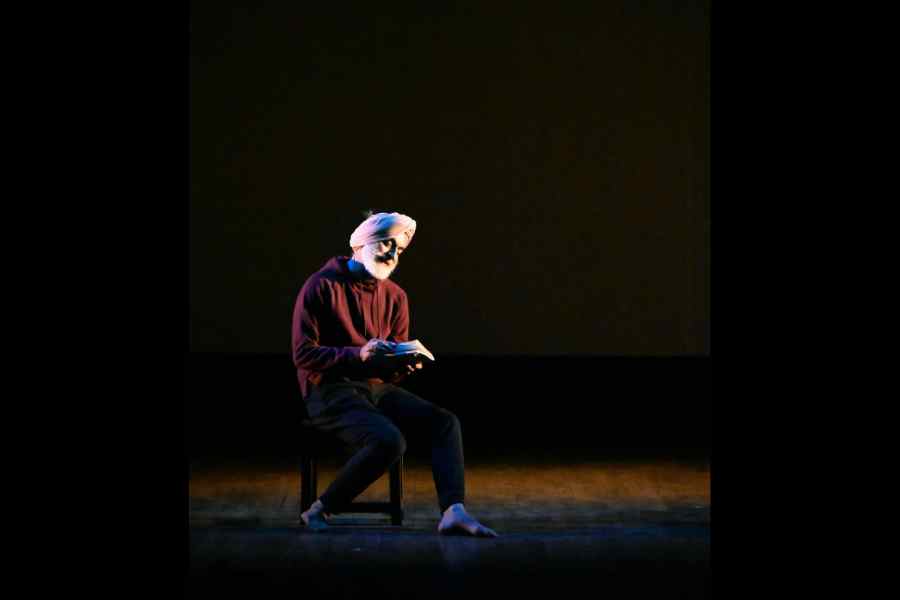

Navtej Singh Johar’s performance Tanashah, based on Singh’s essay “Why I am an atheist” and other pieces written by the freedom fighter in prison, and presented in the city on Saturday, reminds one of these facts, which hit with a stunning force.

The performance, in Punjabi, charts the course of Singh’s intellectual growth, from religious belief to freedom from it, freedom at many levels, not only from colonial rule, but also from caste, class and blind faith. But this critical inquiry was also spiritual. “Adhyatma-nastikata”, a spiritual atheism, was what Singh had chosen.

Kintu, Johar said, is a word that Singh’s prison notes are shot through with. Dancer, choreographer and activist, Johar was performing the piece on the 20th anniversary of Kolkata Sanved, an NGO that works on dance movement therapy.

Kintu. But. The full implication of the word is revealed as Johar raises himself slowly from the floor and slowly ties the turban around his head, assuming full stature. We see Singh in his prison cell, staring death in its face. He does so with amazing clarity, for it is his chosen path. He was 23 when he died.

“Kintu” resounds through Johar’s narration too. He delivers it like a blow, coming back to it like a refrain, and the auditorium is shaken a little. Johar’s 2016 petition had led to the reading down of Article 377 in 2018 and decriminalisation of same-sex relations between consenting adults.

“I was not born an atheist,” Johar says as Singh, who, like Johar, was a Sikh. As Singh writes in the essay on atheism, he was brought up under the influence of his grandfather, “an orthodox Arya Samajist”.

At school, “apart from morning and evening prayers, I used to recite ‘gayatri mantra’ for hours and hours.” He also preserved his “unshorn and unclipped long hair but I could never believe in the mythology and doctrines of Sikhism or any other religion”.

Kintu. His questioning deepened when he became a member of Hindustan Republican Association (HRA), which later became Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA).

He could no longer be “a romantic idealist”. He read Bakunin, the anarchist leader, some Marx, and much of Lenin, Trotsky and others “who had successfully carried out a revolution in their country”, he says. They were all atheists. “Bakunin’s ‘God and State’, though only fragmentary”, he found very interesting. He also read ‘Common Sense’, which he attributes to Nirlamba Swami, but was perhaps written by Soham Swami.

Unlike several of his colleagues, who believed in communist ideology yet hesitated to give up on god, he became convinced “as to the baselessness of the theory of existence of an almighty supreme being who created, guided and controlled the universe”.

The final test was when he was told that he would be given the death sentence. Yet he could not bring himself to pray. One prayed to God for some reward. That is why “He” was invented.

Kintu.

“I, or to be more precise, my soul, as interpreted in the metaphysical terminology shall all be finished there. Nothing further…. With no selfish motive or desire to be awarded here or hereafter, quite disinterestedly, have I devoted my life to the cause of independence, because I could not do otherwise,” he writes.

Singh was hanged on March 23, 1931, at Lahore Central Jail. He had killed police officer John Saunders in Lahore, mistaking him for the British senior police superintendent, James Scott, whom many considered responsible for the death of Lala Lajpat Rai. Singh was also accused of bombing the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi, but given the death sentence for killing Saunders.

He wrote the essay on atheism between October 5 and 6, 1930, to also answer his colleagues who had charged him with vanity for having rejected God and religious faith. “Tanashah” means autocrat, despot, a charge his revolutionary colleagues had brought against him, as they felt he imposed his ideas on them habitually.

It was not just revolutionary ideas and arguments that coursed through his vein, Johar reminds us. Singh weaves into his presentation the story of Heer-Ranjha. Singh was particularly fond of Waris Shah’s Heer and of Ghalib. He was said to sing Heer in prison and kept a book of Ghalib’s poems.

“Call me by your name,” said Johar. True love dissolves binaries; with the love that Heer and Ranjha have for each other, Singh desired freedom. And looked at death straight in the eye.

One of his photographs shows him under arrest, sitting in a cot, his hair knotted on top of his head, his young, lean face looking intently at his visitor.

A lot has to be deleted to fit Singh into the macho Hindu nationalist scheme of things. If we see Singh as its poster boy, we have to remember not only his sacrifice but why he did what he did.