The Congress’s failure to open its account in Delhi for the second successive election hasn’t shocked the top leadership, which knew that the party wasn’t even in the frame and privately conceded that the reasons were both structural and circumstantial.

Dismissing the discourse around Shelia Dikshit and AICC Delhi in-charge P.C. Chacko as irrelevant, insiders pointed out that the Congress didn’t have the organisational muscle to win back its traditional vote bank that has shifted to the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP).

These leaders also spoke of the situational logic of voters not wanting to back the wrong horse in their attempt to defeat the BJP. They insisted that the Congress could have performed only a shade better in a normal election because of structural problems.

Senior leaders believe that the two issues that prevented the Congress from being battle-ready were the leadership crisis and the organisational mess.

While Rahul Gandhi’s exit almost left the party rudderless, Delhi suffered a double whammy as then state president Ajay Maken, who had been tasked with the responsibility of also rebuilding the organisation, resigned. Delay in decision-making, which many believe is a perennial problem of the Congress, ensured that the new president, Subhash Chopra, got less than four months to complete a difficult job.

The resignations of both Chacko and Chopra were accepted on Thursday. After Tuesday’s Delhi drubbing, Chacko had appeared to put the blame for the Congress’s decline in the national capital on the late Dikshit, saying the party started losing ground here in 2013. Dikshit was the Delhi chief minister then.

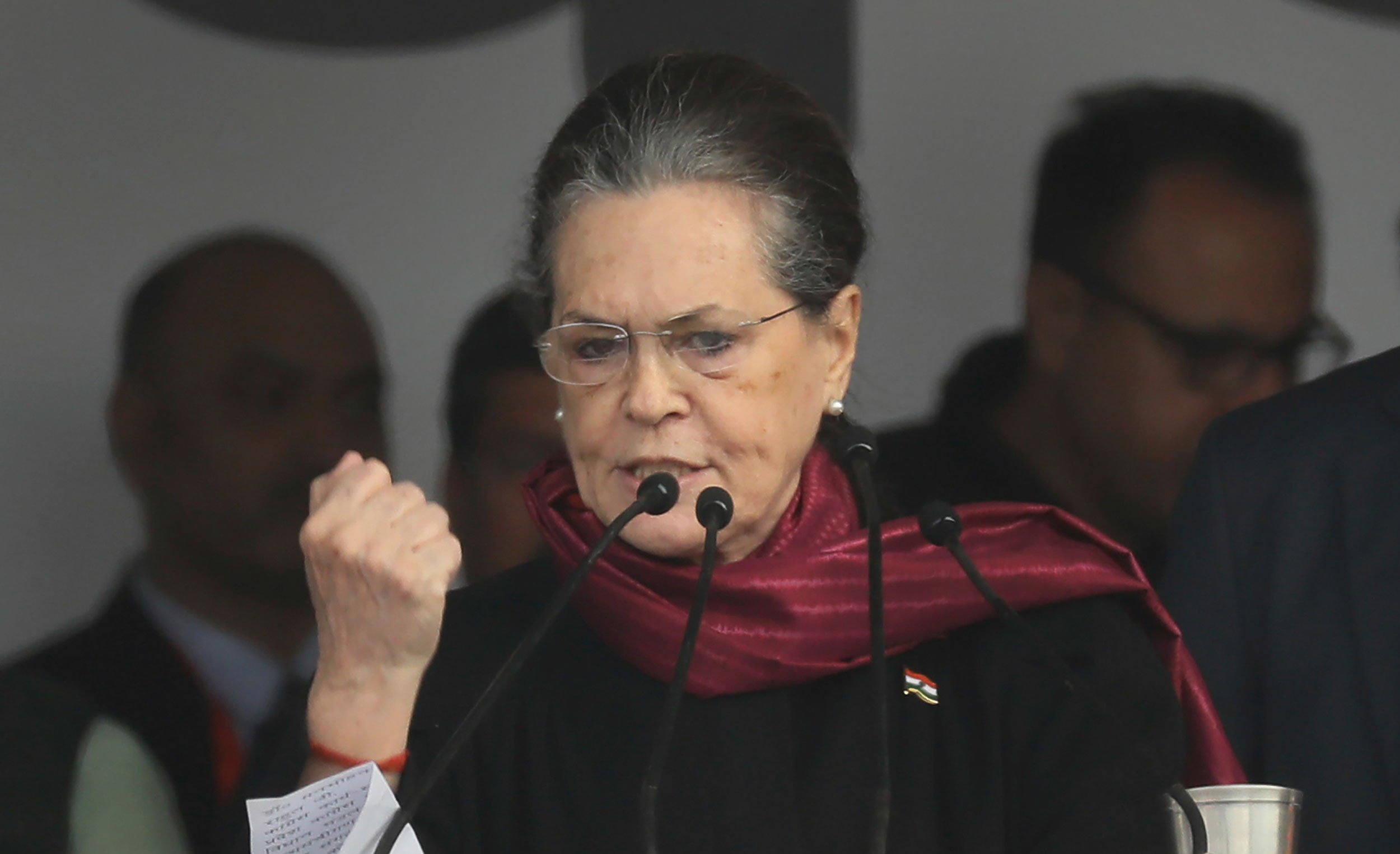

Congress chief Sonia Gandhi has appointed the young Shaktisinh Gohil as the Delhi in-charge.

The majority of leaders argue that five years were squandered in managing factions and establishing personal clout instead of strengthening the organisation and enabling grassroots leaders to grow.

“The Pradesh Congress Committee was not formed for the entire five years even as several presidents came and went. There was no link between the workers and the president. Recommendations were the sole criteria for appointments; merit was ignored. Senior leaders tried to crush talent to ensure the rise of their daughters and sons. Rahul Gandhi failed to change the system during his tenure (as party chief) despite his public proclamations to the contrary,” a Delhi Congress leader said.

Congress strategists, however, admitted that the result could have been better had the overriding purpose of the voters not been to defeat the BJP in an exceptionally polarised atmosphere.

A former Union minister said: “We got squeezed out as the BJP mounted a highly toxic campaign and the secular voters didn’t want to run the risk of defeating that purpose by voting for the Congress. The situational logic of rallying behind the AAP was so compelling that the Congress was forgotten. Otherwise, five-six of our candidates would have won.”

The Congress’s candidates largely agree with this argument but many of them have another grudge.

One of them said: “Political analysis of the result is a bogus exercise. EVMs were fixed. I can prove that to anybody, any agency interested in finding the truth. In booths where we were confident of getting 500, 300 or 100 votes, we got two, 18 and 22 votes. In one booth, where I have over 200 close relatives and friends, I got 18 votes.”

Another candidate echoed the sentiment: “How come almost all Congress candidates were stuck in the 4,000-5,000 bracket? Show me one election in the history of elections where 80-90 per cent Congress candidates got similar votes. We have serious doubts about EVMs.”

The final outcome, however, was that the Congress vote share came down to a miserable 4.2 per cent, a reason for the leadership to be deeply alarmed about. The Congress has a notorious history of failure in rising from the abyss.

In Uttar Pradesh, it has almost been three decades when the party fell from the pedestal and is still struggling to get out of the 6-8 per cent vote share block. In Bihar, the Congress polled almost 40 per cent votes in the 1985 Assembly elections, followed by 24.78 per cent 1990, 16.3 per cent in 1995, 11.10 per cent in 2000, 6.09 per cent in 2005, 8.73 per cent in 2010 and 6.7 per cent in 2015.

Many states have similar stories to tell. In Odisha, the Congress vote share of 39.08 per cent in 1995 kept falling to 33.78 per cent in 2000, 34.82 per cent in 2004, 29.10 per cent in 2009, 25.70 per cent in 2014 and 16.10 per cent in 2019.

In Andhra Pradesh, where the party polled 38.56 per cent votes in 2004, the Congress plunged to 11.71 per cent in 2014 and 1.17 per cent in 2019.

A powerful resurgence remained a pipedream in several other states despite 10 years of being in power at the Centre from 2004 and 2014.