An impending price rise that is likely to raise India’s budget for a key vaccine by less than Rs 100 crore has prompted the government to seek an international donor’s help at a time it has built a showpiece statue for an estimated Rs 3,000 crore.

Public health experts said the situation reflected India’s poor budget allocation for health programmes.

The health ministry is scrambling to avert a possible stock-out of the injectable inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) amid a global supply shortage and a decision by Sanofi, vaccine maker and the sole IPV supplier to the Indian government, to revise prices.

A stock-out would mean the government would be forced to temporarily stop immunising infants with IPV, a vaccine critical to maintaining India’s polio-free status and introduced in the public immunisation programme in 2015.

The IPV does not carry the risks of vaccine-associated polio paralysis or vaccine-derived polioviruses that come with the oral poliovirus vaccine. It’s a key tool in the global polio eradication effort.

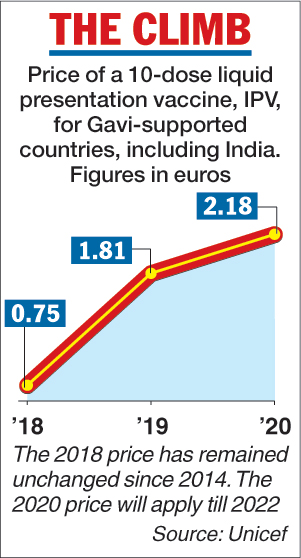

Sanofi has the IPV’s price under a uniform worldwide price revision. The price for India, among other countries, is to increase from the current 0.75 euro (Rs 61) to 1.81 euros (Rs 147) per dose in 2019, and to 2.18 euros (Rs 177) per dose from 2020 through 2022, according to a Unicef document.

The health ministry has approached Gavi — an international organisation that supports immunisation in poor countries — to intervene and help maintain IPV supplies to India.

The vaccine has been available in India through private paediatricians for over a decade, but at higher costs.

The health ministry had introduced the IPV in 2015, relying on Gavi which disbursed $16.3 million (Rs 118.8 crore) for IPV immunisation in India during 2015 and 2016 with the expectation that India would then use its own funds.

“The price increase is global and Gavi is aware that this has put a significant, unforeseen strain on India’s immunisation budget,” a Gavi spokesperson told The Telegraph from Geneva. “Gavi and its partners are exploring options with the Indian government.”

The spokesperson said the price increase had also affected other Gavi-supported countries. “We expect that more supply will become available at lower prices with the arrival of new manufacturers, starting late 2020.”

But vaccine domain specialists say India’s decision to seek Gavi intervention underscores the country’s inadequate budget allocations for its immunisation programme, which depends on Gavi money for, among other initiatives, pneumococcal vaccines and rotavirus vaccines.

Gavi has already disbursed to India $107 million (Rs 769 crore) for pneumococcal immunisation between 2017 and 2019 and approved $55 million (Rs 395 crore) for rotavirus vaccines between 2018 and 2020.

Union health minister Jagat Prakash Nadda and health officials have often asserted that money will “never” be an issue for the immunisation programme.

Two senior health officials declined to speak to this newspaper about the implications of the IPV price rise or reveal how long the already procured IPV stocks are expected to last.

A top paediatrician, virologist and authority on polio, T. Jacob John, emeritus professor at the Christian Medical College, Vellore, said an IPV stock-out would be indefensible.

“Whatever the cost, we have to pay and buy. Gavi may or may not help, but India is no longer a poor country,” John said.

“The health ministry will have to justify a higher budget and protect our investment for polio eradication and secure it through continued universal IPV immunisation.”

John said the IPV market was now a “sellers’ market”, dominated by a giant supplier because of “flawed decisions” taken decades ago. “India had planned to establish a manufacturing plant for IPV in the 1990s, but the project was killed,” he said.

Vaccine experts familiar with the IPV problem said, requesting anonymity, that the global donor community would likely be surprised at India’s request for intervention to address the IPV price rise.

Public health specialists have long argued that India needs to significantly raise government investments in health.

“Investing in children’s health is investing in the country’s economic future. But we shouldn’t view immunisation in isolation. There is an urgent need for an overall health budget increase,” said Thiagarajan Sunderaraman, professor of health studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

“India has the capacity to increase its health budget. This year’s budget for the Ayushman Bharat health insurance scheme is less than what we spent on a statue.”

Telegraph infographic

The budget for the Ayushman Bharat scheme, which provides Rs 5 lakh hospitalisation cover to poor households, is Rs 2,000 crore --- two-thirds of the estimated bill for the 182-metre Vallabhbhai Patel statue in Gujarat, the world’s highest statue.

A UK media report said Britons were “outraged” that the Indian government had spent so much money on a statue while Britain was sending 1.17 billion pounds in overseas aid to the country.

British MP Peter Bone was quoted by The Daily Express as saying: “To take (pounds) 1.1 billion in aid from us and then at the same time spend (pounds) 330 million on a statue is total nonsense and it is the sort of thing that drives people mad.”

The IPV price rise comes against the backdrop of a global supply shortage of standalone IPV. A May 2018 Unicef document had said that sufficient supply to meet the needed two IPV doses was not likely to emerge before 2023.

India, among other countries, gives two fractional doses of the IPV to children at six and 14 weeks after birth, following World Health Organisation recommendations based on research showing that two fractional doses given as intradermal injections produce a stronger immune response than a single full dose.

Vaccine specialists estimate that under the fractional dose schedule, the government needs at least 10 million doses every year to cover all children who receive the IPV through the public programme. A price rise from Rs 61 to Rs 147 per dose means the yearly requirement would cost an extra Rs 86 crore.

Vaccine industry executives say the earlier lower price of the IPV was likely “discounted” and possibly intended to accelerate the IPV’s rollout in low and middle-income countries.