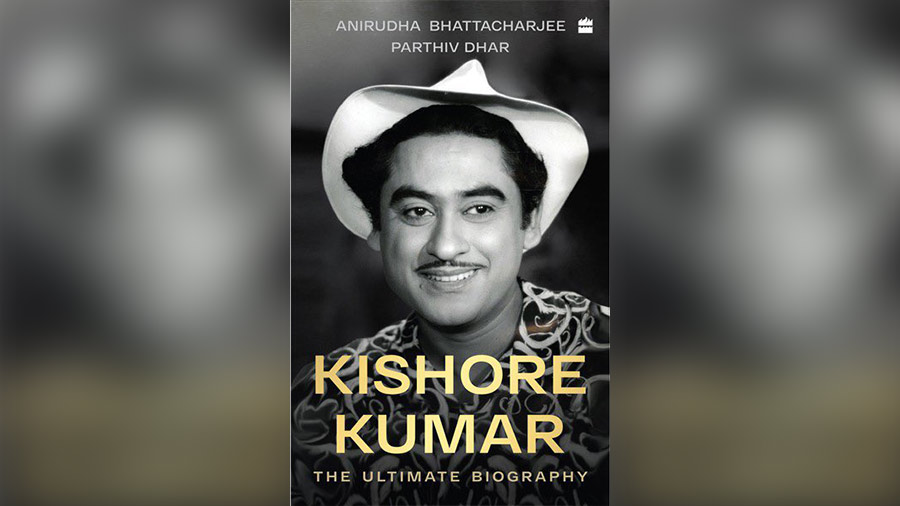

Singer, composer, lyricist, director, writer, actor. Kishore Kumar was all this and more. Apart from Satyajit Ray, I can think of no other person in cinema whose talents ranged across so many departments. As a playback singer, he had no parallels – not Mohammad Rafi, not Hemant Kumar, no one came close. As an actor, he was almost surreal in comedies like Half Ticket and Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi. It is only because we do not view comedy as an artform at par with tragedy and melodrama that his contribution as an actor has not been acknowledged. As a director and writer, he balanced the almost surreal Badhti Ka Naam Dadhi with the minimalist Door Wadiyon Mein Kahin. It is immensely sad that he did not have more films and songs to his credit as a composer and lyricist. Given the range of his contribution and the eccentricities that defined his personal life, a biography of Kishore Kumar that adequately covers his life and times is a tall ask. Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Parthiv Dhar’s exhaustive biography of the legend, audaciously titled Kishore Kumar: The Ultimate Biography, pulls it off – well, almost.

For one, it is a pleasure to come across a biography of a legend like Kishore Kumar that does not seem like an armchair hack job. At close to 600 pages, this one is a painstakingly researched tome. And it does not even talk about his repertoire as a singer in that great a detail. As co-author Anirudha Bhattacharjee tells me, “If I were to make a selection of even a hundred of his songs – an impossible task – and talk about them, this book would have gone beyond 2,000 pages.”

Kishore Kumar: The Ultimate Biography by Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Parthiv Dhar is painstakingly researched. Author

Despite that, what the book covers by way of the trajectory of Kishore’s life is commendable. If I say the authors ‘almost’ pull it off, it is because the language leaves something to be desired. It could have done with a more rigorous copy-edit. One would also have loved to see the authors playing it a little less safe, assessing Kishore Kumar vis-à-vis his contemporaries, or providing a more comprehensive reading of his directorial ventures. Or for that matter talking of what actually accounts for his popularity in the years after his death.

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri: Tell us something about the process of writing the book. Given that all the dramatis personae are long gone, how difficult was it to put information together.

Parthiv Dhar: Anirudha-da and I go back a long way. In fact around 2004-05, we started a campaign for the Bharat Ratna for Kishore Kumar, and did quite a fair bit of work. Probably it was at that time that writing a book on Kishore Kumar crossed our minds. I remember, we were clueless on the structure of the book owing to the multidimensional persona that Kishore was. My visit to Khandwa in 2010 and Anirudha-da’s book on R.D. Burman (with Balaji Vittal) winning the National Award provided the much-needed impetus. Graduating to Kishore was a natural progression.

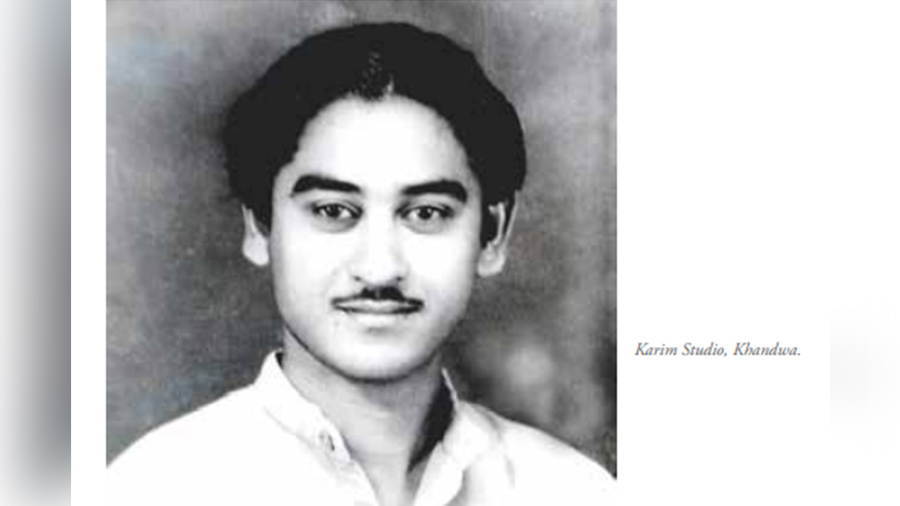

The visit to Khandwa made me realise that it would be a crime not to write a book on him, given the paucity of knowledge. Kishore himself did not help matters much by being extremely economical with the press. The Khandwa and Indore visits brought me close to his friends and their families, his caretaker at the Ganguly House, his college professors who went out of their way in sharing with us breathtaking anecdotes and documents. Fittingly, the book is dedicated to Khandwa. Apart from that we had a fantastic time at Bhagalpur, interacting with his relatives like Ratna-di, daughter of his cousin Arun Kumar, getting a treasure trove of unknown events related to his maternal side. Meeting his secretary Abdul was also a high point in the making of the book.

And the decision to structure the narrative by ragas and their times: dawn, afternoon, evening? You slot Aradhana in the evening….

Anirudha Bhattacharjee: The structure with ragas developed organically given the enormous amount of material we had. The first draft was over 1,000 pages long. Giving it the structure enabled us to get clarity. As for Aradhana appearing under an evening raga, Madhubala passed away in 1969. That was probably a setback. His mother too passed away after a year. Kishore’s tenure as a hero had almost come to an end. He was 40. If we go back in time, K.L. Saigal passed away at the age of 42. Critics were urging Lata to stop singing in the late 1960s. Hence, we equated the time with the evening of their lives. And extrapolated it to Kishore Kumar’s as well. Kishore had great strength of character and turned the tide, but that’s another story.

Kishore Kumar’s photograph at Karim Studio, Khandwa. Author

Would you say that Kishore was the one true maverick genius of Hindi cinema, maybe even Indian cinema?

Parthiv Dhar: Kishore Kumar was a phenomenon, the likes of whom you rarely encounter. He was perhaps the only person in showbiz whose reel and real lives were mirror images of each other. Precisely why there was no reason for him to ‘act’. You never knew whether he was acting on screen or being his own self. That held true even for his real life. His ratio of hits to total songs composed must be one of the highest in the world. He tried everything that the camera and the studios offered but unfortunately there were occupational hazards that clipped his wings. Had some of his unreleased songs and movies seen the light of day, he would have been unassailable. That he did all these only by pure observations and without any formal training made him a genius. As Rama Varma told us in a chat, he had the ability to identify shortcomings in a particular guitar string in the midst of a session without even looking at the guitar or the guitarist. Genius would be too small a word for him. However, we have not assumed much in the book and left the readers to judge for themselves.

What in your view is his greatest contribution to the art of playback singing in India? The one thing that sets him apart.

Parthiv Dhar: Definitely the fact that he made singing appear so easy that emulation became an everyday affair. The clones would, of course, realise that the songs were after all not everybody’s cup of tea. But everyone would attempt a Kishore song. The very fact that he was an actor made him think like one when he would playback. Also, he was perhaps the only one to develop his texture and baritone with infrastructural progress each decade after Independence. This led to him being probably the only one to realise that tragic songs need to make the audience cry, not the singer.

Anirudha Bhattacharjee: All our male singers except Bhupinder and to some extent Yesudas have been tenors. Maybe the timbre has varied, but they are tenors, nevertheless. In my opinion, K.L. Saigal, Kishore Kumar and Pankaj Mullick were tenors who had a unique quality in their voice: ‘dhaar’ and ‘bhaar’ (sharpness and weight). This they used to great advantage. For other singers, it was a case of either/or. Hence, Kishore could playback for Dev Anand using his ‘dhaar’ (Hum hain rahi pyaar ke), complement it with some ‘bhaar’ and ‘mizaaz’ when he sang for Rajesh Khanna (Kuch toh log kahenge), and use his ‘bhaar’ when he sang for Amitabh Bachchan (O saathi re). He also had a strong swarranth, which gave the songs resonance. Plus, his flux density was unique. Even with such a heavy voice, it would remain steady when negotiating long notes, something very difficult to achieve.

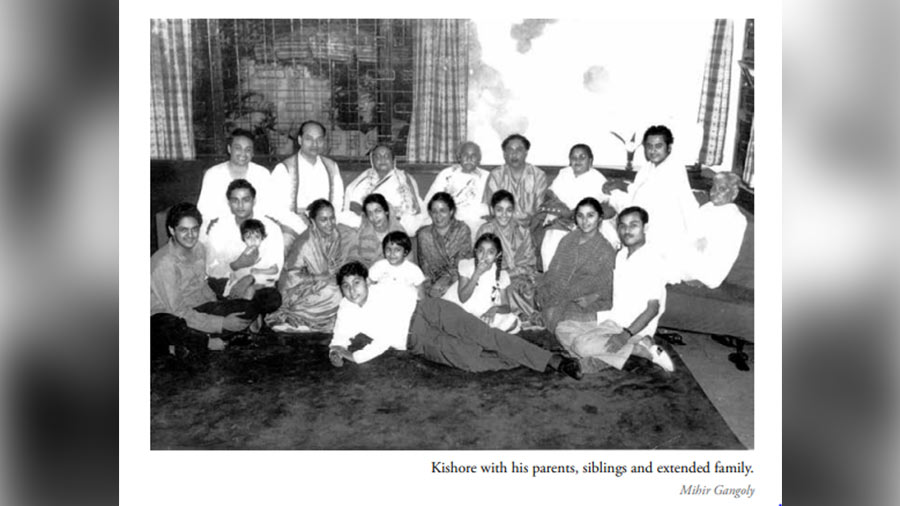

Kishore Kumar with his parents, siblings and extended family. Author

He sang Saigal’s ‘Dil jalta hai’ in reverse, set the Malthusian theory to tune, introduced scatting, yodelling, nonsense/gibberish words (bam chik chik) to music in India… where would you place these innovations in his output? And do you think his comic genius came in the way of him being taken seriously as a singer for the longest time?

Parthiv Dhar: He was born to innovate and his childhood is testimony to that. Lateral thinking and he went hand in hand. Domesticating jackals, singing in reverse, giving nicknames to almost every friend, composer… the list is endless.

However, it is probably not true that his comic persona had anything to do with his singing. He started his career with several serious songs while simultaneously making people laugh in his movies. He gained recognition as a serious actor courtesy his roles in Bandi and Naukri and was known as a sufficiently good actor. He sang for all the top music directors till as late as 1958. That he had a long gap after that could be attributed to his preoccupation with Madhubala’s health.

Let’s talk about him as an actor; would you agree that as a comic he had no parallels in India? Is it only because comedy is not regarded as a genuine art form in India that there has been little recognition of him as an actor?

Parthiv Dhar: A very difficult question and not proper to say that he had no parallels. It should not be forgotten that he was a hero in almost 99 per cent of his films, a fact renowned actors would be proud of. While reviewing Bandi, critics had placed him above his (then) more famous brother (Ashok Kumar). He did not enact comedy, it was in his DNA although by nature he was an equally serious person. His comedy was a mix of slapstick, mimicry, antics. Very few would enact the comic role as a hero for the entire length of time without appearing stale. Kishore Kumar had that quality.

Where would you rank him as a filmmaker? Door Wadiyon Mein Kahin, for example, is a rather daring experimentation, even if the execution is amateurish. Even Satyajit Ray commended its sound design. Your comments.

Anirudha Bhattacharjee: As a filmmaker, he was a lateral thinker. He tried unique subjects. But the issue is that he got entangled in too many activities at the same time and could never devote himself properly to making films. Had he concentrated only on filmmaking, he might have made some great films. Door Gagan Ki Chhaon Mein and Door Wadiyon Mein Kahin could have been classics.

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer.