Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Elippathayam (The Rat Trap), which released in 1981, spins a drama out of the motif of feudalism. Set in 1940s Kerala, Elippathayam draws the picture of the vestige of feudalism co-existing with a matrilineal structure. Gopalakrishnan spins these ideas with a delicate mixture of metaphors and visual motifs, analysing the tragic journey of a family that is caught in the whirlpool of past traditions and structures.

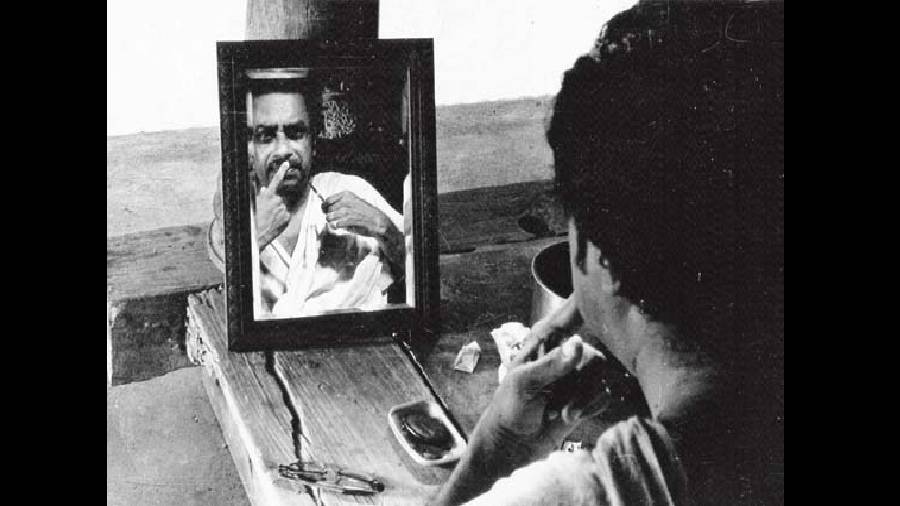

The film focuses on Unnikunju, a middle-aged man with an extreme form of feudal mentality. He is an ego-centric, insensitive, weak-willed and inert individual who likes to live in his own world, in his bid to escape from facing the challenges of the outside world. He withdraws like a rat — a recurring metaphor, that eventually forms the title of the film — into a closed chamber. He suffers from a sense of narcissism and is often found preening at himself, cutting and cleaning his nails, massaging oil on his body and trimming his moustache. He is a symbol of a patriarchal figure in feudal society who is completely dependent on his sisters. Prickly and self-centred, he stays away from Menakshi, a married woman in the same village who tries to seduce him through sensuous gestures. In ways more than one, the world around Unni tranforms, but he refuses to change and sticks to his own reasons.

Unnikunju has three sisters. Janamma, his elder sister, who is married and lives with her children. Sometimes, she visits him to claim her share in the property. His two unmarried younger sisters are Rajamma and Sridevi. Rajamma, who is devoted to Unni, takes care of him like an unpaid slave. She irons his shirts, brings his slippers and umbrella while going out to attend marriage ceremonies, boils water for him, cooks for him and almost forgets her sense of self or individuality. She suppresses her passions, desires and dreams. When she wants to go out of this trap by marrying a man and find a new world of her own, Unni rejects the marriage proposal. She is very loyal to her brother and never utters a single word against him. The youngest sister of the house is Sridevi, a college student who spends her time living in her own romantic and dream world.

The narrative is deceptively simple if one tries to locate it through the way in which the screenplay works. Primarily, it is just a story stylised by Gopalakrishnan through visual metaphors, colour-coded into the depictions of characters where the onus is on the viewer to unpack the story as the film progresses.

What instantly catches the eye is the manner in which Gopalakrishnan stages the film like a cycle of acts. The beginning drives home the primary metaphor, that of a rat trap, chosen to depict feudalism in a vastly changing society. The opening shots of the film highlight certain visual elements, which are suggestive of a feudal establishment — the ancient iron key, a wall clock and an oil lamp. The juxtaposition of the various shots evokes in the viewer a montage-like feeling without providing coherence.

The piercing sound of an airplane flying off-screen has also been used as a creative device in two scenes of the film, first to signify the deterioration of Rajamma and then to show the progress of time. The sound appears for the first time when both Rajamma and Sridevi make an effort to catch a glimpse of the airplane. “Where is it?” Rajamma asks, continuing to look at the sky. Sridevi says to her, “Too late. The plane cannot wait for you.” Rajamma has a sudden spell of dizziness and slumps to the ground. In the second scene, when the sound of the airplane makes its off-screen presence, Rajamma is doing the dishes. Sridevi does not accompany her because by then, she had mysteriously eloped with someone. Rajamma rises to her feet with effort. She looks skywards and as the sound of the airplane keeps growing louder, her abdominal pain keeps increasing, proportionately. Unable to bear the excruciating distress, she reclines on the ground.

Elippathayam is poetic and profound— its vibrant brushes of metaphorical action seeking truth in retrospect. As the story moves forward, Unni finds himself caught like a rat, and in the end of the film, he is thrown into the village pond. Strikingly ordinary in its setting but visually rich and thematically universal, Elippathayam is one of Gopalakrishnan’s finest creations. It is in this restrained yet politically attuned film-making that Gopalakrishnan’s ideas find cinematic harmony.

Gopalakrishnan’s films stand as a stark reminder of how singularly important it is to constantly refurbish one’s apparatus, and explore ideas through art, and not the other way round.