The wooden doors in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali that an irate Indir Thakrun pulls open to leave, angry that she has been accused of encouraging little Durga to steal fruits from neighbours, are ancient, battered, craggy, drained of colour, ready to crumble, yet holding up fiercely, like Indir Thakrun herself. They become her portrait.

These doors were made by Bansi Chandragupta, who is considered by many to have been the greatest art director of Indian cinema. From Pather Panchali to Shatranj Ke Khiladi, he created sets for Ray’s films that were stunning in their details and are remembered as worlds of their own. The courtyard in the Kashi (Varanasi) household that Sarbajaya sweeps and washes in Aparajito is a set. So is Wajid Ali Shah’s court in Shatranj Ke Khiladi, and so are the interiors in Charulata that crystallise in their intricate, exquisite detail — the making of the wallpaper by Chandragupta is another story — even as Charu drifts through her own home, beautiful, lonely and a stranger.

The wooden doors in Pather Panchali designed by Bansi Chandragupta. Sourced by The Telegraph

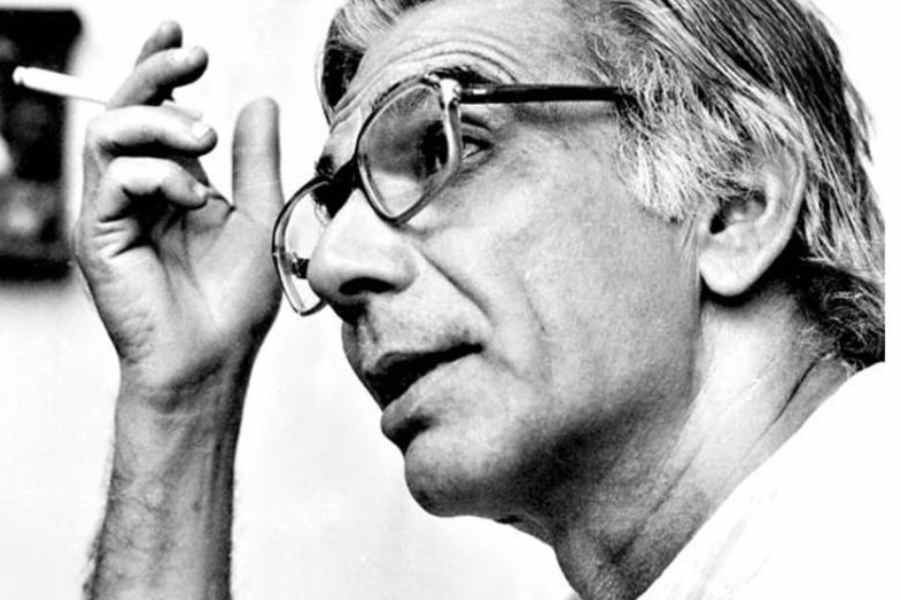

This is Chandragupta’s centennial year. The screening of a documentary on him, Bansi, With & Without Ray, at Uttarpara Cine Club on Sunday was an attempt to remember his remarkable life, which is almost forgotten. The film, made by Arindam Saha Sardar, is an account of Chandragupta’s life and work and tells the story with sensitivity and depth without delving too much into biography.

It also reminds us that Chandragupta had not worked for Ray alone.

Chandragupta met Ray in the 40s, after coming to Calcutta from Srinagar, having followed artist Subho Thakur and wanting to be an artist himself. He had been born in Sialkot, now in Pakistan.

He worked as an art director with Ray for Panther Panchali (1955), which changed Indian cinema, pushing it away from the theatrical and the melodramatic towards modern realism. Chandragupta, who formed a celebrated trio with Ray and cinematographer Subrata Mitra, is one of the architects of this change.

A still from Satyajit Ray’s Jalsaghar. Sourced by The Telegraph

In the documentary, filmmaker Moloy Bhattacharya talks about the Pather Panchali doors. The house was a real one, in Boral village on the outskirts of Calcutta, where Pather Panchali was shot, but the doors were added. Two new doors were broken down, drained of colour and worked on meticulously by Chandragupta.

“They became Indir Thakrun’s reflection,” adds Moloy Bhattacharya.

The process was called weathering, which is ignored now. Weathering adds to the film the markings of time, which turns an inanimate object into a lived reality.

Chandragupta was a master of this art. He breathed life into things and created worlds, lovingly, meticulously and painstakingly. A friendly, humble, joyful person, loved by his friends, he spoke his mind and did not stop working till he was satisfied.

Still from Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi. Sourced by The Telegraph

Even Ray, known for his stern adherence to schedule, would wait for Chandragupta to finish a set.

This quest for perfection could lead to brilliant innovation. For Sarbajaya and Harihar’s house in Varanasi in Aparajito, which was meant to be located in a narrow alley, Mitra wanted dim light on the set and wanted it covered from above. Chandragupta did that; light from below came back reflected from the top as if faint light was filtering in. “This was the beginning of bounce lighting,” said Somesh Bhattacharya of Uttarpara Cine Club at the screening, though no one thought of publicising it as that.

The entire train in Ray’s Nayak is a set created by Chandragupta. The zamindar’s house in Jalsaghar was the Nimtita palace, but the dance hall was a set in Aurora Studio, Calcutta.

Chandragupta had not been able to study art at Visva-Bharati, but art’s loss was cinema’s gain, though he continued to draw. It was on the sets of Jean Renoir’s film The River (1951), which was shot in Calcutta, that Chandragupta worked with renowned production designer Eugène Lourié and was introduced to set-making.

From Pather Panchali through the 60s, Chandragupta worked with Ray.

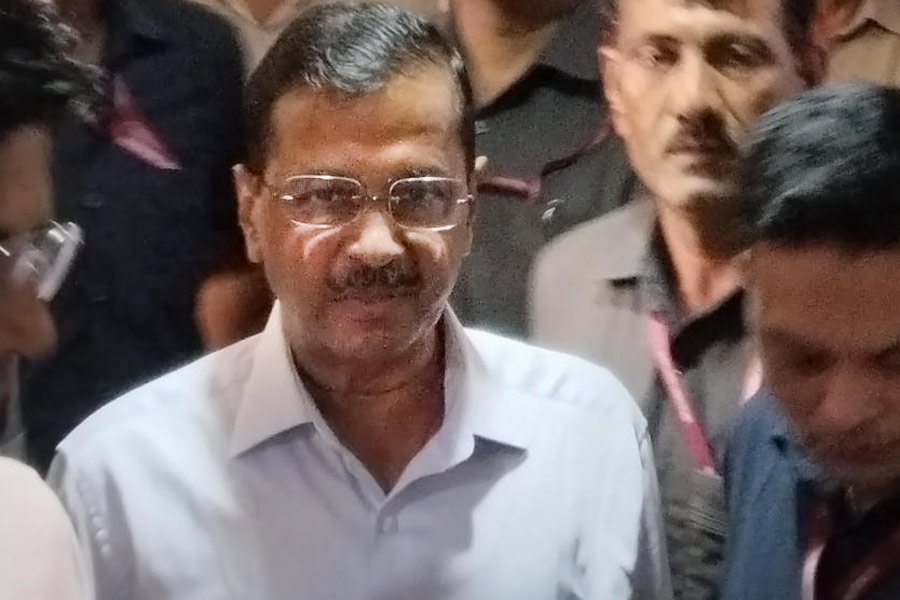

In Bengal, and outside, Chandragupta had worked with several eminent directors, including Mrinal Sen, Tarun Majumdar, Aparna Sen, Shyam Benegal, James Ivory and Kumar Sahani. In the documentary, Mrinal Sen remembered how, for his film Calcutta 71, Chandragupta created the interior of a home collapsing in the rain. Majumdar recalled how for his film Palatak, Chandragupta would pay for work on the set from his own remuneration. He was not looking for money; he was looking for creative satisfaction. “He told me if you don’t make Balika Badhu, I will never work with you again,” Majumdar says in the documentary.

The documentary, says its maker Saha Sardar, interviewed people who knew Chandragupta closely. With directors Mrinal Sen, Majumdar, Aparna Sen and Moloy Bhattacharya the documentary, made in 2012, also interviews film editor Dulal Dutta, cinematographers Soumendu Roy and Purnendu Basu, and art directors Suresh Chandra Chandra and Kartik Basu. “We chose to talk to those who knew Chandragupta’s work closely, the primary sources,” says Saha Sardar.

In the early 70s, Chandragupta left for Bombay, now Mumbai, to work for the Hindi film industry. Despite his brilliance, work did not come easily to him. His quest for perfection often stretched schedules and budgets and all producers were not equally keen to employ him. He refused to toe the line in other ways — he lost his job in a film when he refused to stop smoking in front of Kanan Devi.

He got work in mainstream films, including in Jungle Mein Mangal (1972), for which he built a set so spectacular that it became a tourist attraction. But this was not what he was looking for.

When Ray decided to film Shatranj Ke Khiladi (1977), he needed Chandragupt back. The film showed Chandragupta’s deft hand at recreating grandeur. This would be followed by a fruitful phase. The year 1981 would see the release of three remarkable films, all of which had Chandragupta doing the sets — Shyam Benegal’s Kalyug, Muzaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan and Aparna Sen’s 36, Chowringhee Lane.

Chandragupta would not see the release of all the films. In June 1981, when he was visiting the US with Ray and cinema critic Chidananda Dasgupta, he died of a heart attack. He was 57.

In his early youth in Calcutta, Chandragupta had also been part of Calcutta Group, a radical artists’ collective, with Subho Thakur, and had been part of founding Calcutta Film Society. He would be part of the adda at Paradise Cafe attended by Mrinal Sen, filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, composer Salil Chowdhury, lights designer Tapas Sen and many others who believed in the Left ideology. As “unemployed youths”, Chandragupta and Tapas Sen had shared a room.

The documentary on him is shot in black and white. “In a world that is full of colour, a new dimension emerges if colour is drained,” says Saha Sardar. Some things need to be shown starkly.