There lived a man, a Bengali man born in Varanasi, who, in 1955, got himself a milk van and some friends and travelled from Paris to Calcutta. Over the next six to eight months they met people and slept in tents while he recorded the sights and sounds of every town they stopped at before crossing borders, one after the other. The photographs, in black and white; and the sounds in the form of recorded music from Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy, Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, Iran, Afghanistan, and then India and Pakistan.

I learnt about Deben Bhattacharya (1921-2001) after being driven in a car for 15 minutes from my home to his on Southern Avenue. He was this “gypsy” from the holy town who spent his life documenting myriad fragments of human emotions borne out of lives spent in deserts, hills and by rivers. These recordings were catalogued and some released as LPs, one of which is titled Men and Music on the Desert Road. Shortly after he returned to Paris, he penned an account of his travels. More than six decades later, the manuscript has been published by Sublime Frequencies as a book, Paris to Calcutta, which, as his friend and one-time curator at Victoria and Albert Museum in London W.G. Archer notes in his introduction, serves two key purposes. Not only did the recordings introduce the West to unfamiliar music, it also shows the intermingling of Arab, Persian and Indian influences. It allows us a glimpse of how national temperaments and religions thwart or stimulate creative expression and how Indian music has been central to this process.

“Deben lived for music,” his wife and soulmate, Jharna Bose Bhattacharya, tells me over tea and Turkish halwa at their apartment replete with artefacts, posters and paintings, at least one of which is a Jamini Roy original. “He was always running away from conventions. Recording music, writing books and translating poetry became his purpose,” she says, quoting Marilyn Monroe: Imperfection is beauty, madness is genius and it’s better to be absolutely ridiculous than absolutely boring.

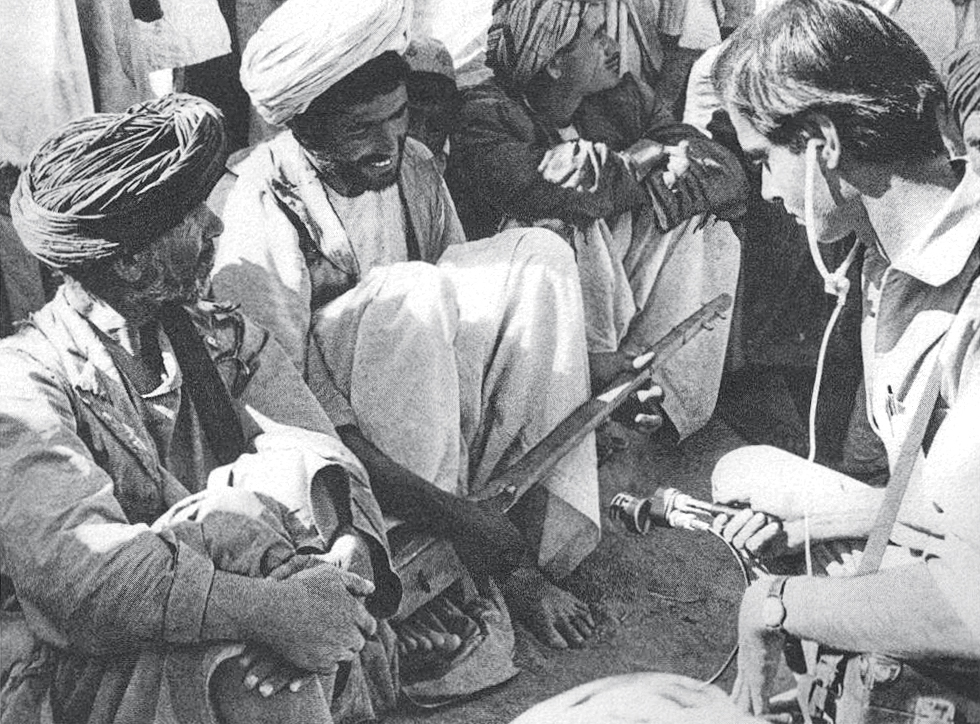

Long before USB cards and iPods, Bhattacharya would have to lug around a heavy Gaumont-Kaale spool tape recorder that needed car batteries to run. “I love my subjects. I make the films and do all this work primarily for myself, and then, secondly, to share with those who can enjoy with me. Thirdly, I make them to survive, doing work I like to do,” he said in an interview in 1982.

During his 1955 odyssey, after Belgrade, Bhattacharya and his two companions, one of whom would do the driving, reached Alexandroupolis in Salonica, where they called on the Lindsays, a Quaker family that ran a school for girls. There, he recorded the girls singing and dancing the lemona and yerakina. This forms the first track of the first of four CDs included in the book. In Turkey, days after a riot, the spoils of which reminded him of violence-scarred 1946 Calcutta, he meets a man singing love songs from Anatolia with a cümbüs (a guitar-like instrument). He encounters an octogenarian tribal singer at Gaziantep playing the cura saz (a small member of the lute family). The funeral chant, mevludu nevebi, he records at Kilis on the Syrian Turkish border, reminds him of the songs of Bedouins and “their desire to make themselves heard in the vast empty spaces of the desert”. He would meet the Bedouins in Amman, where the 35-year-old chief, Sheikh “Lawrence” Shaalan, is named after the brave Englishman, an associate of his father during the Arab revolt in World War I. The Bedouins sang traditional songs (disc 2, track 4) of the desert and camels, accompanying themselves on a string and bow instrument made of wood and horse tails. As the van heads towards the mountains of Afghanistan, he gets to hear more music and more instruments, like the santoor, tar, setar, zarb, violin, clarinet and accordion.

Bhattacharya died in 2001 in Paris, by when he had bookended a veritable archive of 400 hours of audio recordings of music, more than 1,500 photographs, some in colour, 22 documentary films and several books; notable among them The Mirror of the Sky on Baul songs, La Semaine Sainte en Adalusie on Andalusia, and Visages d Ísrael on the music of Israel.

The cover of a collection of his field recordings Source: From the book 'Paris to Calcutta'

Bhattacharya recording workers at Mundigak, Afghanistan Source: From the book 'Paris to Calcutta'

Bhattacharya’s admirers agree his recordings are invaluable. “Aajke je amra prithibi jurey gaan geye berachhi, eta to Dada recording korchhilo bolei (No one would have known about us if Dada [Bhattacharya] had not recorded and written about us),” Jharna recalls Purna Das Baul telling her last year, referring to the 1954 encounter the musicologist had with Purna Das’s father, Nabani Das, at their home in Siuri. Sometime later, that recording was heard in New York, prompting beat poet Allen Ginsberg to seek out Nabani Das. Soon after, the wandering minstrels would get their ticket to the world.

About the LP, among the many who sing its praises is Frank Zappa. “Actually, I think my playing is probably more derived from Eastern music, Indian music… for years I had something called Music on the Desert Road, which was an album with all kinds of different ethnic music. I used to listen to that all the time,” the American rock icon known for his non-conformist experimentations told Guitarist in 1993.

Artistes such as Deben Bhattacharya are a rarity. They live off their passion, take a road and make it their own. I take mine, 15 minutes in a car; thankfully, I am back home. A George Harrison song plays in my head:

I keep travelling around the bend

There are no edges, there is no sides

Oh yea, you just don’t win’

It’s so far out — the way out is in

Bow to God and call him Sir

But if you don’t know where you

are going

Any road will take you there.