The indigenous man, curled up in a foetal position, was asleep, unaware of the tight, menacing circle forming around him. Those who made up the circle that was closing in on him near the jetty at Havelock Island had come from near and afar to visit the Andamans. There was a band of Israelis who peered at the supine figure; some American tourists were busy photographing what, they thought, was a near-naked apparition with a crop of matted hair, a stub for a nose, and dark skin. The Indians in the crowd were the most excited, and brutal. A group of Bengalis kept pointing at the aboriginal person and whispered excitedly, “Jarawa, Jarawa.” Another industrious lot gathered a stick, began to poke him in the ribs, and started recording the man’s discomfort. But this circus of perverse pleasure came to a halt with the arrival of two policemen. The men in uniform, as is the wont of uniformed men the world over, kicked the indigenous man awake and began to lead him away.

The drama that unfolded on the Havelock jetty seemed to condense the history of the civilisation project in the Andamans in a few sordid moments: settlers arriving, peering at, encircling and, finally, kicking the indigenous people out of their own turf. As with all colonisers, of imperial or of desi lineage, the violence inflicted has as many shades as those of the sea that surrounds the isles.

In Havelock, the incursion was explicit.

But there is another kind of violence that, its perpetrators believe, is righteous. To savour a taste of this brew, one must leave Havelock, take one of the boats to cross an emerald stretch of water, and head towards Port Blair, which houses, among other “attractions” for tourists, the Anthropological Museum. This institution is a telling register of the civilisation project in the Andamans. The museum masks, with the help of photographs lit up in dim sarkari light and chilling statistics framed on giant boards, the unambiguous proof of depredation by projecting the evidence as an endeavour to develop, what bureaucratic lingo insists is, “friendly, peaceful contact”. A board hung on one of the walls documents the rapid decline of the population of the Great Andamanese, the Onge, the Jarawa and the Sentinelese — the savage sacrificed at the altar of civilisation. Inside the desolate rooms — the flow of tourists is usually a trickle — are mounted photographs of earlier visits by officials and researchers, always smiling — to hide the nerves? — bearing gifts for their targets. It must have been this sense of entitlement, the assuredness of the knowledge of what is ideal for a people with a distinct way of life, that prompted the tribal welfare body to introduce the Onge to shelter and food that are completely unsuitable for them. The “moral” roots of this infringement even makes the neo-colonisers imagine the natives as willing collaborators in the project. The photographs of tribal schoolchildren dressed up in starched, stiff uniforms in the Anthropological Museum inevitably strikes a chord with the handful of visitors.

But the most lethal weapon unleashed on the Andamans, its original inhabitants and its ecosystem, is tourism. It is this malignancy that forces administrators to slice open shelters for the Jarawas with a road that brings with it not just unwelcome guests, but also disease and pollution.

The sea, even though it casts a spell the colour of turquoise, lies as ravaged as the land. To discover this defilement, take another, overcrowded boat and journey to North Bay Island. Once there, dive underwater. For hydrophobes, there is also the semi-submarine, an underwater contraption that plays loud music and serves cold drinks and potato wedges to its teeming hordes, as it glides past stretches of dead coral, their white, shrivelled textures reminding the indifferent explorer of the price of predatory exploration.

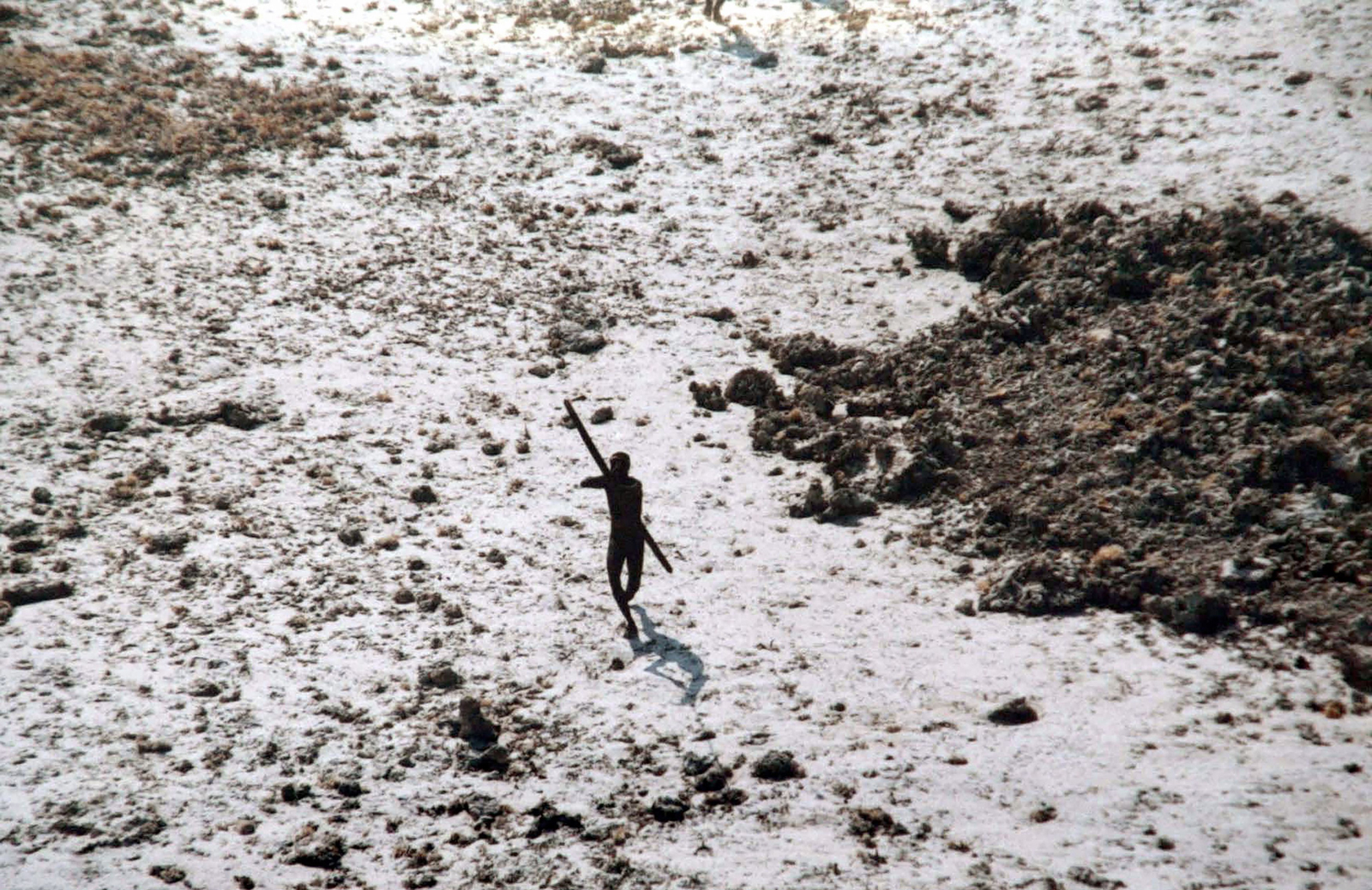

Finally, violence — the retaliatory violence of the wronged — is always disproportionate. A preacher from a distant land journeys towards the Sentinelese in contravention of the laws of India, convinced that he carries with him a precious light. A besieged people, their anxieties heightened by years of encroachment, resist his overtures and, unfortunately, kill him. There is uproar and indignation, against the doomed visitor. But the Great Civilising Project may have already done the trick, rendering the claim of the indigenous people on savagery as immutable.

The Sentinelese, the last men standing in the Andamans, could expect more boats bearing a dangerous light.