Scene I — A bylane in Salt Lake

There I was, stranded on the eastern fringes of Calcutta. It was my seventh attempt to meet thespian Manoj Mitra in the last seven months. Something or the other always happened at the twelfth hour — his shifting work schedule or his wife’s poor health. Six previous attempts and I had never managed to make it to his house and now, when I was so close to my destination, I learnt that the 84-year-old was someplace else.

After several attempts, Mitra took my call but only to say, “I am at the municipal office.” Not again, I groaned inwardly. And that was when I noticed it, the unkempt garden adjoining the freshly painted two-storey house.

Mitra’s magnum opus was Sajano Bagan; a well-laid-out garden is how the title would translate into in English. Mitra wrote it in 1977. Two years later, Tapan Sinha turned it into the now iconic Bengali film Banchharamer Bagan. Mitra, then 40-something, himself played the protagonist, Banchharam, the 90-plus gardener.

I headed for the municipal office.

I had met Mitra six months ago at the studio of Hindusthan Records in central Calcutta. He was recording a podcast of Kak Charitra, a satire he had written decades ago. The one-act play is about a playwright and a neighbourhood crow. In the podcast, Mitra played both the roles. Every punchline left us — sound recordists, archivist-singer Devajit Bandhyopadhyay, who was the anchor of the podcast, and myself — seismic with laughter.

Kak Charitra is a critique of society; it is about hypocrites of every shade. In particular, it takes potshots at a philanthropist, a sadhu and even playwrights of the 1970s who preferred adaptations of Brecht, Pirandello, Ibsen and Sophocles to the point of ignoring Bengal’s stories, its wealth of folklore legends and literature.

By the time the podcast ended, Mitra looked exhausted. The managing director of Hindusthan Records urged him to revive his 1985 comedy Dampati in the podcast format. The older man looked excited, smiled and nodded.

Scene II — Municipal office

After a few minutes of peeping into this room and that, I discovered the man and legend; he was waiting for an officer. He pointed to an empty high chair and said, “I’ve come to meet him.” The clerks on that floor were full of chatter. They were debating whether Mitra’s best performance was in Lathi, Shatru, Ghare-Baire or Banchharam; the first two being mainstream Bengali potboilers and the third, the Ray film based on Tagore’s novel.

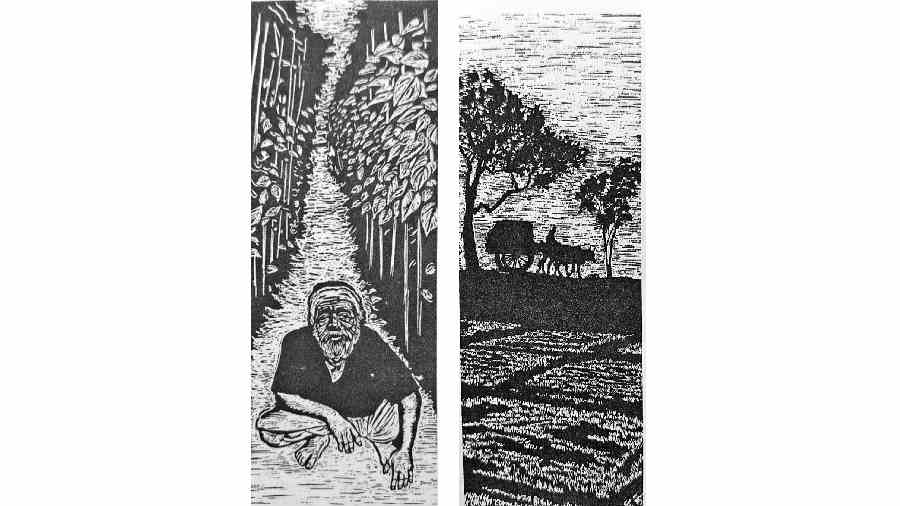

By this time it was clear that Mitra would not let the interview begin unless he had accomplished his municipal mission. I took out a copy of his memoir Galpana, turned to the page with the lino-cut illustration of Banchharam and placed it on the table. Mitra’s expression changed. His eyes took on a sparkle and when he opened his mouth to speak, I realised he had been transported to his birthplace — Dhulihar village in Khulna, which is now in Bangladesh.

He started to talk about a gardener he remembered from the time he was a fouryear-old. “Banchharam Kapali must have been 90. He had a tiny frame, couldn’t walk, just about dragged himself against the earth. He owned a betel grove. I would see him whenever I accompanied my grandmother to his garden to buy the sweetest betel leaves of our village.

Between the flashback and the promised interview that was yet to begin, the occupant of the empty chair, the assistant engineer, arrived. He and Mitra hugged each other. The younger man apologised profusely for keeping “Manojda” waiting. Then he hastily started browsing some files and informed Mitra that his papers were in order.

At some point, another topic sprang up. The official mentioned something about Mitra’s “community movement” against the developer who has built a mall near his house.

Mitra recalled the time they created such din. “One morning, the payloaders were tearing down the old market. The ground shook and a bottle of ink tipped over the script of a play. I have made it a point not to visit that mall ever.”

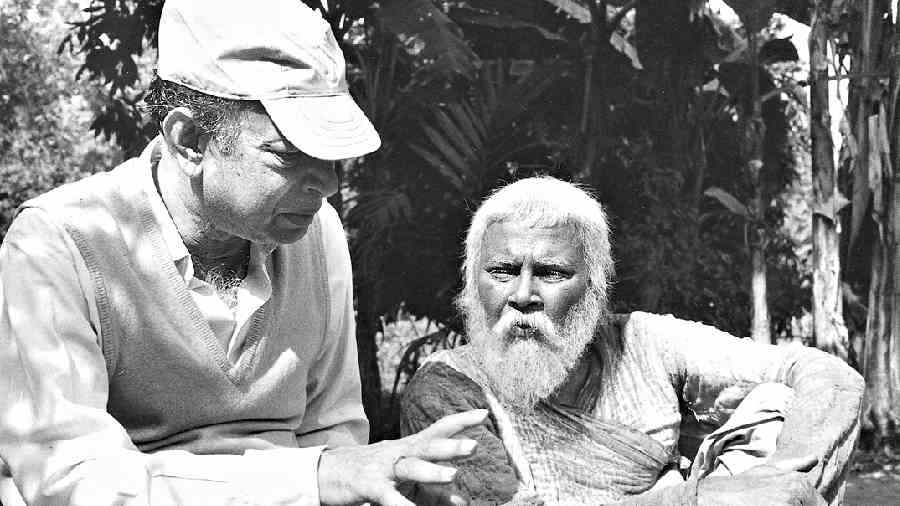

AT PLAY: Tapan Sinha directs the young actor in Banchharamer Bagan

Scene III — Coffee shop

For the first time in the last two hours, Mitra and I were alone. We chose a seat next to the window. When he crinkled his eyes at the first sip of Darjeeling tea, it occurred to me that my mental image of Mitra had been very different. In my imagination, he looked like a very elderly, very rustic Banchharam. Mitra, the person, wore a deerstalker cap, had a slight limp and eyes like laser beams scanning the surroundings for minute details. He pointed to a largish cookie and said, “That tastes good, just like our desher pithe.”

Mitra is one of those people who have worked across mediums — stage, films, television, radio and now, new media. He acts, writes and directs for all types of theatre platforms — professionals, amateurs, hobbyists, clubs and students. His plays have been translated into multiple Indian languages and have been directed by stalwarts of Indian theatre such as Habib Tanvir, Rajin- der Nath, Ratan Thiyam, Bibhash Chakraborty, Kumar Roy and Soumitra Chatterjee. He told me how “Ratan” had sought his permission before adapting Sajano Bagan to the Manipuri stage. Mitra said, “He said he would have to make the protagonist, the gardener, a woman, because in Manipur, the cultivators and farm labourers are mostly women.”

Mitra has been equally at ease about acting in Bengali arthouse films directed by Satyajit Ray, Tapan Sinha, Buddhadev Dasgupta and Goutam Ghose as in “mainstream” films made by Shakti Samanta, Prabhat Ray and Anjan Chowdhury. He said he doesn’t believe in walls between different mediums. And when I spoke with some incredulity at this ability to adapt effortlessly to different formats, he said, “The directors and producers of various fields also adapt, they also tolerate me.”

At the sunlit cafe, Mitra flipped the pages of his memoir with great tenderness, and while doing so said, “The 1960s and 80s were tumultuous decades, they constantly inspired one to create. The political upheaval made us anti-establishment; unhindered we wrote, produced and acted in so many plays.” This was the time when Mitra wrote classics such as Chak Bhanga Madhu, Narak Guljar and Aswatthama, decimating the ruling Congress party with his pen. “But they never banned or stopped us,” he adds.

Does he regret that all anti-establishment sting has disappeared now? Mitra replied, “It seems we are in status quo, but there’s an undercurrent of rebellion that may erupt any time.” He adds that a talented bunch of actors in his theatre group Sundaram is getting ready to stage Sajano Bagan afresh. “I plan to recast and rewrite it, and launch the new version in January.”

Mitra writes incessantly. He writes plays for Puja numbers. In the last few years, he has been using episodes from the Mahabharata and Ramayana to raise his voice against injustices against the common man.

Much has changed over the years, but what has not is Mitra’s focus and dedication to the marginalised, to telling the stories of their trials and tribulations, all of it presented in his characteristic wry style. Sajano Bagan, too, was about a peasant who stood up to a tyrannical feudal lord and his greedy son.

Mitra said fondly, “Tapanda watched the play and summoned me to his home in New Alipore.” He tells me how the film was shot in a real garden in the southern fringes of the city, how Uttam Kumar was initially chosen to play the zamindar and not Dipankar De.

After about an hour’s chat Mitra said, “Let’s call it a day.” His ailing wife’s attendant needed to break for lunch. I watched him as he opened the gate, got in, walked down cap in hand.

Scene IV — Bookstore on College Street

A Saturday evening. The second part of Mitra’s memoir Manojagotik or Of the World of Manoj is about to be released. Mitra is seated with the rest of the audience. He is dressed in a blue pullover and the characteristic cap. He seems radiant.

We chat about how ordinary human beings, in the course of their life’s journey, inspire him to write plays — a snake charmer, a neighbour, a village playwright, his grandfather.

He talks about the last few years of his grandfather who suffered from a prolonged illness and desperately waited for death.

Mitra says, “He was so reluctant to relocate to Calcutta from our village home. When my father broke the news of a planned flight from what was then East Pakistan to a locality in Beliaghata, in eastern Calcutta, my grandfather burst into tears. He was scared to live in an alien city,” says Mitra. His grandfather’s agony pushed him to write his first play Mrityur Chokhe Jol in 1959.

It is a busy space and our conversation is random, completely uncharted. Mitra recalls the time he met Satyajit Ray. “When he met me after the first show of Bachchharam, he said, ‘Oh! I thought you must be an old man. It never occurred that you are so young.’”

What are the changes one is to expect of the production of Sajano Bagan in the new year? Will Mitra play the lead this time too? “Not me,” he replies. “It’s time to nurture new talents.”

I buy a copy of the new memoir and also take out the earlier one, Galpana, from my bag, and sit down beside him. That day I had forgotten to get the book signed. He happily scribbles something and returns both the memoirs. Two short lines in Bengali script. They read: “Prasuner boi, Amar soi.”