THE ROYAL ALBUM

A memory wafts through Umang Hutheesing’s mind when we ask him what luxury means to him — his grandmother in a starched white khadi sari, smelling of mogra. For Hutheesing, “a royal cultural revivalist” or an “old-fashioned designer” as he describes himself, that is luxury and also royalty. The royal regalia is luxury, too, because it is handmade and has the grandeur of nostalgia and not wealth. “Our family has a heritage of 1,200 years,” says Hutheesing who restored his ancestral haveli in Ahmedabad and loves sporting khadi kurtas because that’s how he has grown up.

Hutheesing started designing royal costumes six years back; his label, Umang Hutheesing, is for those who “understand and appreciate” his aesthetics, one that celebrates India. t2oS caught up with the Ahmedabad-based revivalist of royal costumes when he was in Calcutta for The India Story Wedding Diaries. For this chat, oh yes, he was in a khadi kurta!

The first thing I did was to make clothes for the royal families; royal families who wanted high quality of craftsmanship and very focused original, traditional garments.

Unlike what people imagine, our Indian royals are very humble and elegant people. They do not wear anything that is excess. In fact, they dress in the most humble way. The women are generally in light chiffon saris, and the men in trousers and shirts. It is only on occasions that they wear elaborate clothes. I make clothing for several royal families.

Soon I realised that royal families buy things for an occasion. If you have to survive, you have to make clothes for a larger audience.

My clothes are not daily wear

When I delved into it, it wasn’t easy. The first exhibition I had was in 2012. Not a single piece sold and I realised why. I had a fantastic setup in my haveli with all the outfits on beautiful mannequins and 800 people for dinner. It got lost in showbiz and it intimidated people. I was, in their view, grander than them. How could they come and say ‘I want to buy this’?

Also, it was very expensive. So, I started making them less embroidered. We can use the elements and say, do a border around the neck or the cuffs. So, basically elimination of excess to create elegance.

But my clothes are not daily wear. I make clothes for anybody who is willing to understand and appreciate my aesthetics. What I have consciously stayed away from is the entertainment industry. Fashion, style and consumerism are driven by Bollywood. I have worked in television and know that Bollywood is an illusionary horse that people ride their dreams on. I am not a dream seller. I make clothes for the princess. I make very limited pieces; no stores. I love creating. You create for somebody.

Though one is moving on with the times, it is still in keeping with the classical format. The bootis are still classic. Maybe the fabric on which it is embroidered has changed. What is classic is the quality of handcraftsmanship and originality of design. Anyone who understands culture and history and embraces that is a princess.

This is the sixth year of my label. In six years, what did I do? I have showcased 300 creations of mine in museums.... I did a show in Buckingham Palace. The Obama government asked me to do a show in the Roosevelt House. The Queen of Bahrain hosted my exhibition.

There’s a lot left to do. I am just a custodian of heritage and anyone who wears it becomes a patron.

History in costumes

We are a textile family and have a reasonably large collection of royal costumes to leave as a legacy for the future generation. The family has its roots in the old capital of Osia, 1,200 years ago, which was near Jaisalmer.

There are about 2,000 pieces and the collection has been put together over several generations. Many of them are our family-owned costumes and some are acquired. It is documented and preserved in a private collection in my house and haveli in Ahmedabad. A lot of these royal costumes have been exhibited in museums around the world.

We have a wonderful collection of folk embroidery and some of the styles are almost extinct now. Whether it was Nagaland or Kutch, each community had their own style of embroidery and clothing, which has largely disappeared now. There are beautiful Mughal period costumes and also from the Raj period.

In our culture, we reuse things. A sari would tear and it would be used to make something else. It’s not just us but traditionally also, people never threw away textiles. So, it is difficult to say what is from which period.

There are diverse things, from beautiful angrakhas and cotton clothes to lavish chogas from the Mughal period. There are some exceptional pieces, like a sari made of pure platinum zari for one of the royal families. These are exceptionally rare pieces.

Legacy of crafts

Our family set up a large number of textile mills in the British times. So, we have been in textiles for more than 150 years, besides other things. The first fashion show in India was held in Ahmedabad in the Calico Mill. My grandfather’s sister Sarojini Hutheesing opened the first boutique in India in 1922 in Bombay called Chitra. She revived Benarasi weaving at that time. My great-great grandfather and Louis Tiffany started the first design firm of Asia in 1881.

We won nine gold medals for being the finest design firm in the world, in the World Expo of 1900 in Paris when the Grand Palais was built to house the World Expo. We executed the interiors of the east wing of The White House and the Kensington Palace. We made furniture, jewellery, carpets.

In 2010, I had an exhibition in Paris and then French president Nicolas Sarkozy and his wife Carla Bruni were its patrons. Designers like Ralph Lauren and Hermes attended it. What we showed was material heritage.

The feedback was that India was one of the few countries which still has a living heritage of textiles and since we have such a huge resource, why don’t we also do something for the living heritage?

How we preserve

Textiles are organic and they deteriorate and you have to restore them. We have to restore our collection of old costumes. We have highly skilled people doing it, people who used to work in various royal poshakkhanas or our temples, doing embroidery.

Till the 1970s, till we had the abolition of the privy purse and all the royal families were dismantled, they had these poshakkhanas where there were lots of karigars working. So, the craftsmanship was quite alive. Then people who had magic in their hands became labourers. It was all about finding these people and training them and re-establishing their connections with textiles. I have people from Bengal, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Kashmir and Madhya Pradesh. At any given time, there would be 50-odd karigars. You won’t find more highly-skilled karigars than them.

We also have our own staff to preserve these pieces. Once a year we have to air all the costumes. During winter, we put them out in the sun and then put them back with mul mul inside. We use cloves and neem leaves, not chemical balls. Like Ayurvedic medicines, there are traditional methods of preserving textiles.

Why I started designing

Preserving material heritage, that is my historic collection, and using it as a resource to create modern magic of living heritage is a combined joy.

My resource base or my knowledge base was my collection of arts and antiquities. I didn’t go to a school to learn stitching and sewing. I cannot even stitch a button, but I can design. It’s in my blood. A lot of these crafts were completely lost. What most designers make is really not a sherwani. A sherwani has a particular cut. There is a difference between a long coat and a sherwani. All lehngas are not the same. Keeping them in their original style of cuts has its own beauty. All ghagras are not the same. A Rampur ghagra, a Jodhpur ghagra, a Jaipur ghagra… they have different cuts and kalis. You have to educate people about all this.

Fortunately, we had a lot of books in our poshakkhanas, so I could train people.

The royal wardrobe

In the industrial age when machines are creating most products, it is important to preserve the living traditions of hand-craftsmanship and the textile traditions of India are an important living heritage. The cuts and costumes worn by the aristocracy and our ancestors are fast becoming relics. It is important to keep these alive. And that is why in 2012, I started my label.

Umang Hutheesing boasts a heritage from 1,200 years ago Sourced by The Telegraph

Princess Mriganka Kumari of J&K, granddaughter of Karan Singh in a Hatheesing design Sourced by The Telegraph

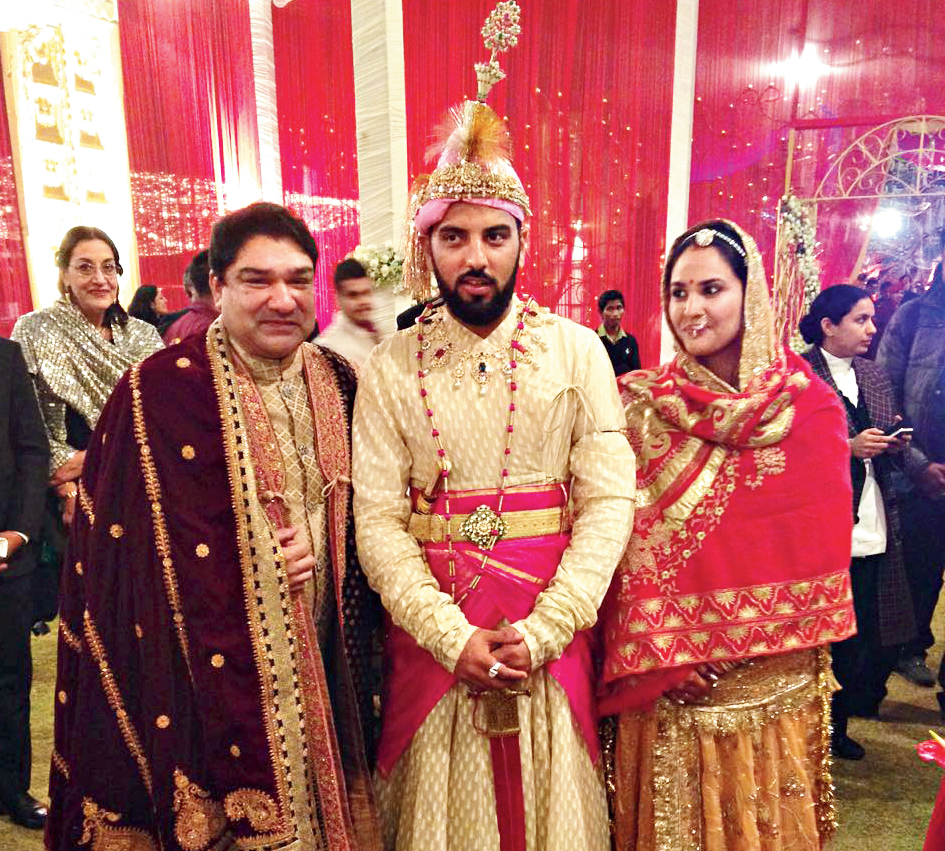

Umang with MK Lakshyaraj Singh Mewar of Udaipur and his bride Nivritti Kumari of Odisha. Sourced by The Telegraph

The Les Derniers Maharaja, an exhibition of Royal Indian Costumes from the Deepak & Daksha Heritage Collection, curated by Umang for YSL Foundation, Paris, in 2010, which was on display for five months Sourced by The Telegraph