Even history favours those born of privilege. They who are conceived in deprivation must scramble to piece together that generational mirror smashed to smithereens by callous circumstance. You could describe The Cutlass by Trinidadian Vinay Harrichan as yet another community history project but it is really an exercise in yearning. It is a frenetic hunt for information about a time and context, which a certain generation forsook; the same their progeny now wants to know, perhaps to see better the figure in the mirror.

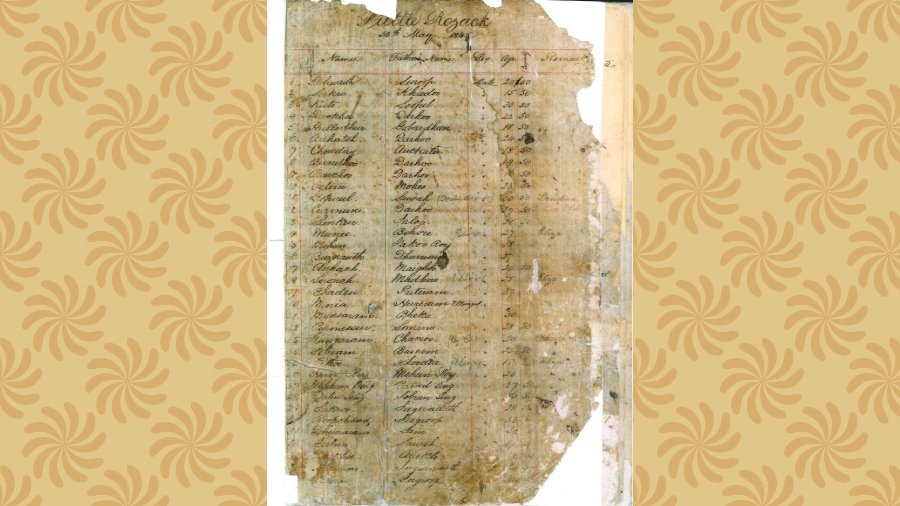

Beginning 1845, close on the heels of the formal abolition of slavery, till well into the 1920s, British colonisers shipped thousands of Indians from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and fewer numbers from Bengal and south India to their colonies in the Caribbean, Fiji and Mauritius, Africa, Central and South America. While some were promised better prospects in the new land, most were tricked or forced into going. Hundreds died from abuse or disease onboard the packed vessels that transported them. Others touched dry land but never really arrived where they wanted to.

It might not sweeten history, but sugarcane plantations were an important part of the Caribbean economy of the 18th and 19th centuries. Those who arrived in Trinidad in the mid-1800s replaced African slaves in these plantations. Harrichan’s maternal great-grandparents had been sugarcane cutters on the estates. Nobel laureate V.S. Naipaul’s grandfather had worked in one such plantation. The first cricketer of Indian origin to play for West Indies Sonny Ramadhin’s parents too worked in one.

Little wonder then that The Cutlass, launched in August 2020, should take its name from the agricultural tool used by Indian indentured labourers to cut sugarcane.

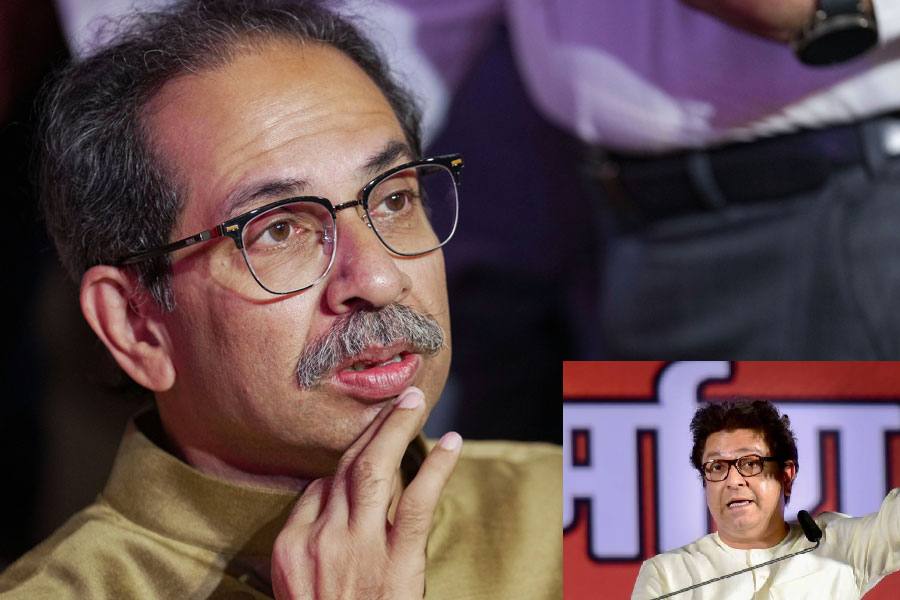

A 1945 photographs of two East Indian women employed by the Royal Air Forces, at Piarco Airport in Trinidad and Tobago, sourced from the Imperial War Museums (UK) Courtesy, The Cutlass

Harrichan, who is the founder and curator of the social media platforms, has been described in many places as someone “doing a deep dive into history that is not taught”. Does that mean the history of indentureship is not taught in the Caribbean? He says, “In the 1970s and 1980s, my parents grew up in parts of Trinidad where the majority of the population was Indian. In school they learned that the ship Fatel Razack had landed in Trinidad in 1845 with the first set of jahajis or indentured labourers. Beyond these little else was taught to them.”

Harrichan’s parents were the first generation in their families to finish school, which means their parents would have relied almost solely on family tales. Until the mid-1900s, most schools were Presbyterian or Catholic institutions and indentureship did not occupy a significant portion of the curriculum. That changed as more Hindu and Muslim schools came up and with the formal recognition of Indian Arrival Day.

“But still, most people are unaware of early Indian history in the Caribbean. Major movements and leaders, institutional prejudices, elements of indentureship like wages and abuse... much of that is not widely known,” says Harrichan.” There are currently campaigns to sue the education boards in the West Indies over discrimination in the curriculum,” he adds.

The Cutlass Instagram page will strike Indians in India as a collection of oddities. Random jottings about community practices, legacy words. Here’s one: “‘Tarkari’ is a word forum in Bengali, Hindi, Bhojpuri and Nepali... It is used for curried vegetables. In the West Indies, many do not know these roots and say ‘to-carry’ or ‘tal-curry’.” Lyrics and video clips of Bollywood songs — Nanda singing “Bhaiya mere rakhi ke bandhan ko nibhana” to Balraj Sahni in the 1959 film Chhoti Behen — whose strains have long floated out of the memory of most Indians here. There are interview clips of community elders singing bhajans, talking about “muluk” and “choka”. The relevance of all of this is decoded by Harrichan, a data engineer by profession, who has been researching Indo-Caribbean history the past seven years.

List of the 225 adult labourers who arrived in Trinidad aboard the Fatel Razack, sourced from The National Archives of Trinidad and the Indian High Commission Courtesy, The Cutlass

Perched on the main branch of the same culture, it might surprise some of you how generations later the good, the bad and the ugly lose individual attributes and all become equally important and part of an amorphous and prized thing called “ancestral culture”.

Says Harrichan, who has interviewed community elders about their childhood and the stories they heard growing up, “The older women show me their godnas or tribal tattoos that were necessary in order to get married. The men tell me about the panchayat system. I hear stories about the Brahmin, Chamar and Chatri castes. It pains me to hear about the abuses of indentureship, the way women were assaulted and how so many men committed suicide, how wages were withheld or land seized. For a while Hinduism and Islam were not legally recognised and that is why Indian children and marriages were considered illegitimate. People would work in the sugarcane fields and then come home to read the Ramayana or the Quran.”

You might remember the migrant labourers here in India who were all but forgotten when lockdown was announced, and their collective walk homewards. You might remember those who fell asleep on the rail track and got run over; their speckled orphaned rotis that became a metaphor of class amnesia. Would it have occurred to you that their children and their children and theirs’ would also want to know their complete story, end to end, beyond metaphor, beyond pandemic?

Cut to Harrichan. He says, “Without knowledge of history how can we understand, appreciate and preserve our unique identity? I want to learn as much as I can and share all of that with others because our stories are not just ones of trauma but also triumph.”