In March 1965, Louis Armstrong came to East Germany for a series of concerts. It was a tightly packed tour: The jazz superstar performed 17 shows in nine days in five different cities of the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR).

Around 45,000 East Germans saw him play live with his All Stars band.

The political background behind Armstrong's concert series turned it into an event that was both "outstanding and ambivalent," says Paola Malavassi, co-curator of a new exhibition that takes the historic event as a starting point. "I've Seen the Wall — Louis Armstrong on Tour in the GDR 1965," is on show at Das Minsk, an art museum in the former East German city of Potsdam, right outside Berlin.

Paola Malavassi and Jason Moran, curators of the exhibition 'I've Seen the Wall,' on show at Das Minsk museum Deutsche Welle

The GDR's ambivalent views on jazz music

The Berlin Wall had been built less than four years earlier by the GDR; the satellite state of the Soviet Union aimed to stop the "brain drain" of educated and skilled workers from the East to the West. Amid Cold War propaganda, the GDR's ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) increasingly hardened its stance towards popular music throughout the 1950s and 1960s. By the end of 1965, during its plenary session, the party officially unveiled its hard line against all cultural manifestations that were deemed to promote the West's "nihilistic" and "pornographic" values.

Jazz was viewed suspiciously too. GDR leader Walter Ulbricht is said to have described it as "the ape music of imperialism."

But the GDR authorities' attitude towards the music genre also fluctuated from the 1950s to the 1970s, with some officials recognizing its power as the "people's music" because of its African-American roots.

"Satchmo," as Armstrong was nicknamed, had been invited by the Deutsche Künstler Agentur, the GDR state agency in charge of determining which foreign musicians could perform in East Germany, as well as which East German artists were allowed to play abroad.

A symbol of 'friendship between peoples'

Politically-toned speeches were held upon Armstrong's arrival in Berlin. The head of the GDR artists' agency, Ernst Zielke, praised the African-American musician's visit as a symbol of peace and socialism; it was a celebration of the working class and friendship between peoples.

Louis Armstrong arriving at the East Berlin airport in 1965 Deutsche Welle

On the other hand, the US was also keen to send jazz musicians to Soviet countries, as "good-will ambassadors."

The GDR had allowed the Armstrong concerts to take place in halls with a capacity of 2,000 to 3,000 seats, but it had also assigned the Stasi, East Germany's secret police, to surveil the concertgoers, fearing riots.

The tour is remembered as having given a boost to the East German jazz scene, with the music genre serving as a symbol of freedom, as noted by jazz musician Jason Moran, co-curator of "I've Seen the Wall," in a podcast released as part of the exhibition.

'I've seen the Wall'

The title of the exhibition refers to a statement made by Armstrong at a press conference in East Berlin during the tour.

A West German journalist asked him to comment on the Berlin Wall dividing the city. In his answer, Armstrong avoided the political debate: "I've seen the Wall … and I'm not worried about the Wall … I'm worried about the audience I'm going to play to tomorrow night!"

However, he then added, "I can't say what I want to say, but if you'll accept it, forget about all that other bulls***t."

Deutsche Welle

The interpreter nervously chuckled, and did not translate Armstrong's reference to self-censorship into German, simply mentioning the singer's use of a "strong expression" along with his call to concentrate on the music.

Zielke, the director of the GDR's artists agency, promptly closed the topic at the press conference by stating: "Anyhow, it's interesting that the only political question of this kind is not from us, but from a Western outlet. We are delighted to note this."

Solidarity with the US civil rights movement

Just as interestingly, even though they didn't refer to the GDR's state of affairs, all previous questions by East German journalists were equally political.

They were rather interested in finding out Armstrong's stance towards the civil rights movement. Just as the influential trumpet player was touring East Germany, the Selma to Montgomery marches were taking place in the US. The non-violent protests, held to demonstrate against racial repression against African Americans, had Martin Luther King Jr. as their figurehead.

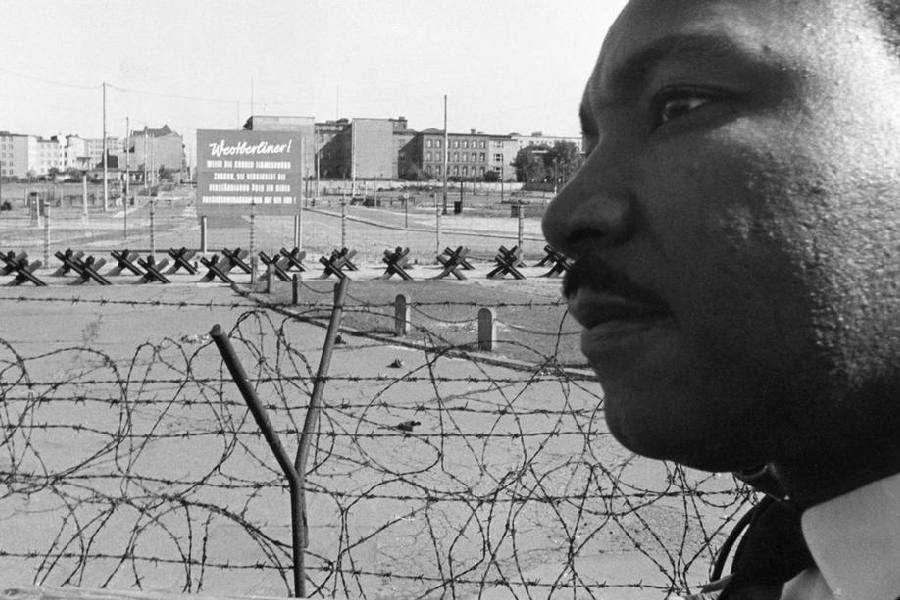

A few months previously, in September 1964, King had given speeches in West and East Berlin. In both parts of the divided city, he advocated reconciliation; the pastor and social activist also compared the divisions between African Americans and white people in the US and those between Germans living in communist and democratic systems.

King's emphasis on their common struggles was particularly moving for East Berliners — but made US officials nervous. The GDR and the Soviet Union often highlighted how racial violence in the US was a sign of the failure of the American society; East Germans were strong supporters of the civil rights movement.

'Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music,' wrote Martin Luther King in another speech, written for West Berlin's first jazz festival in 1964. Here he stands next to the Berlin Wall Deutsche Welle

'I do my little part'

Asked about the marches, Armstrong explained that his contribution to the movement was rather to play everywhere in his home country and to build connections with his white fans, even in the racially segregated South. "I just do my little part, which some of them [the activists] don't do. But I do," he said at the East Berlin press conference.

By then, Satchmo was somewhat embittered of being accused by fellow Black Americans of not doing enough for the civil rights movement. Though the jazz icon mainly avoided politics, he did famously criticize the government's lack of action in the Little Rock Nine case in 1957, when nine Black students enrolled at a formerly all-white school in Arkansas faced horrendous treatment by those who were protesting against desegregation.

Many African-American activists had maligned the jazz superstar for not being vocal enough, but as curator Jason Moran notes, they came back over time and said, "Well, actually, Louis was most profound in his activism." They had by then realized that there are different ways people could manage to "get in the room to spark change."

And for Moran, that's what Armstrong did. As one of the first Black superstars in the US and internationally, he found "his way inside rooms in a way that the person on the street doesn't. And they do need each other as a community of activists to spark a kind of change, possible change."