Ghazal maestro Pankaj Udhas goes down memory lane and discusses music trends ahead of his Calcutta concert Jazbaa at Science City Auditorium, in association with The Telegraph, on Saturday.

You will be performing live in Calcutta again this Saturday. Do you remember your first concert in the city?

Calcutta is an integral part of my musical journey. My first album Aahat came out in 1980 and the second Muqarrar in 1981. Both became very popular among the youth. I first performed in Calcutta in 1981. It was a solo concert organised by some students at the auditorium of a school called Bidya Bharati. I remember I got phenomenal response and I was called back to Calcutta within a gap of a month or two. Since then, I’ve been coming to Calcutta regularly. By 1986, I had performed at Nazrul Mancha, Kala Mandir and Birla Sabhagar. The icing on the cake was performing in January 1986 at Netaji Indoor Stadium. It was a ghazal concert, not a Bollywood one. I had no supporting act and it was completely sold out with 12,000 people. It’s unbelievable, the love people here have for my kind of music.

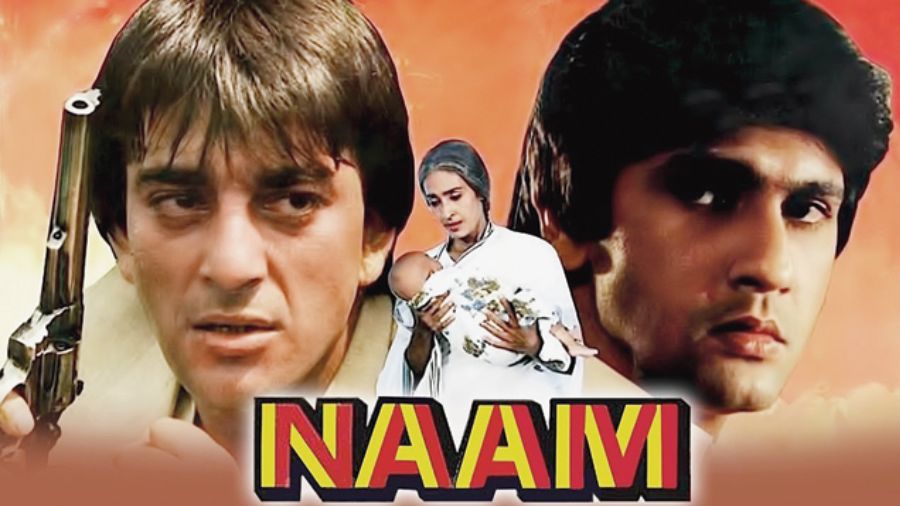

So Calcutta did not need Chitthi ayee hai to embrace you. Naam (in which the song featured) released later that year, in August.

Yes. Subsequently I performed in open-air venues like Salt Lake stadium along with other artistes like Lata (Mangeshkar) ji, Manna (Dey) da and Hemant Kumar on the occasion of Bengali New Year. It was organised by a famous minister (Subhas Chakraborty). I was fortunate that I got a chance to sing there for half an hour. The stage was made right at the centre of the stadium and there were good 60-80,000 people in the stadium. I remember when I started singing and did my first alaap, the applause was like a cricket applause! I felt like I had hit a six!

You have completed 42 years in music and are doing a series of concerts to mark the milestone.

Yes, I wanted to talk to the audience and take them through the journey. So I felt that even if it is happening two years later, I must do it. At the Science City programme also, I will be going down memory lane and sharing anecdotes with the audience.

You have announced a show at the Sydney Opera House also.

I am very fortunate to have performed at every prestigious venue in the world, starting from the (Royal) Albert Hall in London to Carnegie Hall and Madison Square Garden in New York and the Shrine auditorium in Los Angeles. Sydney Opera House is the only venue that was left out. A family friend suggested that we do a concert there to celebrate my 40 years’ journey. It was supposed to have happened two years ago but because of Covid we had to postpone it. We are doing it now on September 4. It was planned so well that we are sold out four months prior to the concert. I think I have completed my wishlist in terms of the top venues in the world.

Does your songlist or communication with the audience change when you perform abroad?

In my entire career, I have never believed in emotional blackmail. I’m sorry to say this but there are a lot of artistes who do so. For example, I know what kind of emotion a song like Chitthi ayee hai evokes abroad. But I don’t tell people that I am so sad that you are living abroad and I feel so much for you. I start singing without saying a word.

How did your journey start? You were sandwiched between two musical brothers and even had an Urdu teacher, right?

We are three brothers coming from Gujarat. When I was growing up in the late Sixties and Seventies, the only music known to people was either classical music or film music. My eldest brother Manoharji wanted to be a playback singer. Thank God that he succeeded. I was still in college studying. By then, we had shifted from Rajkot to Mumbai. Manoharji was always very close to Kalyanji of the Kalyanji Anandji duo, who came from Kutch, a Gujarati-speaking region. Kalyanji was a connoisseur of good poetry. He told Manoharji that, ‘You are doing very well but to make your Hindi sound even better you need to get the correct diction so nobody can point a finger at you’. Kalyanji put him in touch with an Urdu teacher, a fine gentleman called Syed Mirza. He used to come home to teach him. I used to sit a little away from the two of them. One day after the session got over, I gathered courage and asked him: ‘Can I also learn Urdu from you?’ His teacup almost fell from his hands. It was the hippie era. I had long hair and I used to wear bell bottom pants. He looked at me and said ‘Beta, you are from the new generation? How will you learn Urdu?’ I said I might look like a kid from the new generation but I still want to learn Urdu. So he said he would give it a shot for two-three sessions and see. Manoharji was quite shocked but he knew my love for ghazals.

How did you become fixated on ghazals?

In those days, the only source of music was the radio and in my house, the radio used to play 24x7. All India Radio used to regularly play Begum Akhtar. Her voice was unbelievable and I got attracted to her style of singing. That’s how I got involved in singing ghazals. When we shifted from Rajkot to Mumbai, I was introduced to the music of Mehdi Hassan. I developed a passion for singing this form of music as a 20-year-old. I remember an inter-college competition in which I was participating from St Xavier’s College. All the participants were singing film songs. I was the only one to sing a ghazal. When the results were announced, I got the first prize. The great Jaikishen of Shankar-Jaikishen was one of the judges and he told me that they gave me the first prize as I was original.

These days on music reality shows and in concerts, singers try to sing all kinds of songs. But for ghazals do you think it’s essential to not sing anything else to maintain the purity of the singing style?

I’ve always said that there is a certain boundary as far as ghazal singing is concerned. You cannot cross that line. Jagjit Singh, for example, used the guitar and saxophone but he did not go beyond a point in his singing and his style.

So he experimented with the orchestration but not with the singing. But would you allow a ghazal singer to sing, say rap or folk songs or other kinds of Hindi film songs as well?

I’ve done Bollywood but then if you listen to all those songs, most are what we call in Urdu ghazalnuma, meaning ‘like ghazal’.

Talking of orchestration, an instrument which goes with ghazals like a jugalbandi is the harmonium. But the next generation uses a keyboard!

I see a lot of it because on Instagram, a lot of people tag me. Many young girls and boys are singing ghazals with a guitar now. I cannot sing without a harmonium. I guess that’s the price you have to pay for modernisation.

Talking of your songs in films, there’s a practice in Bollywood of recording a song with multiple singers and using only one in the film. In your case, there was one song in Baazigar, Chhupana bhi nahin aata. Were you told it would not be part of the film?

I’ve never shared this story with anybody. The song was first recorded in my voice. The film was produced by the music label Venus. They wanted shoot the song with me but when they called I was on tour in America. They had got the dates of Shah Rukh Khan and others, and said they could not wait. So they got Vinod Rathod to sing the song.

Mohra and Yeh Dillagi, both released in 1994, and your songs in those films were probably the last we heard you in movies. Why has Bollywood almost stopped using ghazals?

Because of the change in the style of making films, the use of music has also changed. Films hardly have songs these days and even if there are two or three songs, they are mostly in the background. Music has lost its importance in cinema. Another change is that the film may be in Hindi but all the songs are in Punjabi. I have nothing against Punjabi but that is the scenario today. The only music which is really making rounds of the music circuit is dance music.

So no situations of introspection with lyrics of depth...

It’s all gone. Which is why people don’t even remember who the lyricist is, who the singer is or the music director is.

You came up with an album titled Nayaab Lamhe in 2018. Was that your last album?

Yes, in December. After that, I’ve done a couple of singles. There are no takers for physical CDs. You expect people to download the whole album from iTunes? That also doesn’t happen any more. So we’ve come to a point that if you want to do some music, do a single and that’s it. In Mumbai, we had this music shop called Rhythm House. When I was in college, I remember going there, picking up a few long play records and going inside the booths they had. There was a headphone and you’d listen to a couple of tracks and select which records to buy. Then in the evening, you’d play those records at home not once but maybe three times. That’s how music was heard by people. Obviously your involvement with a particular song or a particular genre of music was far more than what it is today because today it’s all in the mobile.

You were planning a YouTube channel dedicated to ghazals. How is that coming through?

I am almost ready. Hopefully I will be making an announcement within a month. The channel is dedicated to three genres — ghazals, sufi and qawali. It will have all artistes participating in this and we will find new talent as well. I am very keen that we do fresh recordings. We may include recordings of the doyens as well.

Other than Begum Akhtar, which artiste has had the biggest influence on you?

My real guru is Lata Mangeshkar. When I was six years old, I started listening to her on the radio. When I was eight or nine years old, I started singing her songs. I remember singing Ae mere watan ke logon at a function and people went crazy. Her songs have taught me the art of expression — how you utter each and every word — her style of singing taught me how you bring in the right emotions at the right time.

There is a song of hers (Lata Mangeshkar’s) in the film Razia Sultan — in Urdu, it’s called nazm — Ae dil e nadan… this nazm is like a chapter from the text book. Every singer should listen to it and learn about pitching and expression

I’m very fortunate that over a period of time we developed a bond. Every year, I would visit her during Ganpati festival and she would sit with us and chat about all kinds of things. There is a song of hers in the film Razia Sultan — in Urdu, it’s called nazm — Ae dil e nadan… this nazm is like a chapter from the text book. Every singer should listen to this and learn how your pitching is and expression is.

One hears you have planned an autobiography.

Yes, I am halfway through so hopefully I will launch it by December. My phone has a voice recorder, so I keep on doing voice notes. There’s someone who’s doing the transcript for me.

Three favourite ghazals in films

Aap ki nazron ne samjha (Singer: Lata Mangeshkar, film: Anpadh, music: Madan Mohan, lyrics: Raza Ali Khan)

Ruke ruke se kadam rukh ke (Singer: Lata Mangeshkar, film Mausam, music Madan Mohan, lyrics: Gulzaar)

Man re tu kaahe na (Singer: Mohd Rafi, film: Chitralekha, music: Roshan, lyrics: Sahir Ludhianvi)