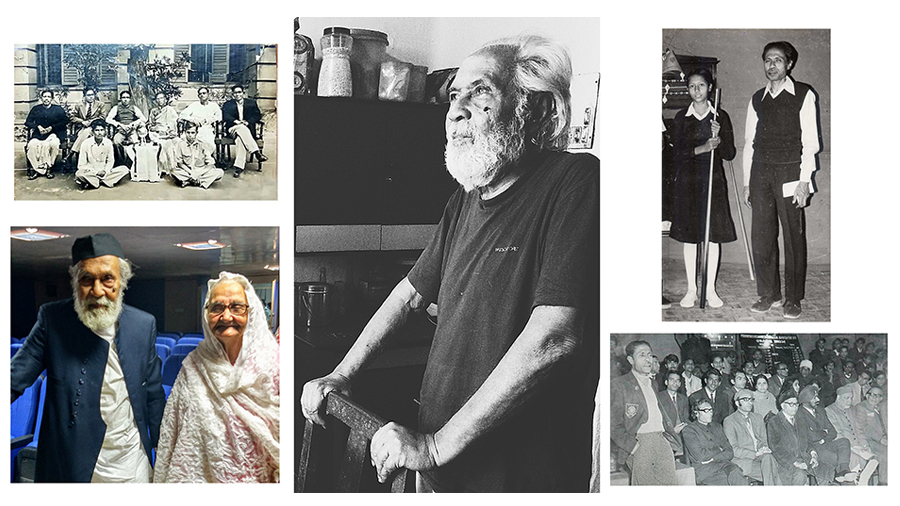

The news of the death of Prince Kaukab Quder Sajjad Ali Meerza, great-grandson of the last Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, at 87, flashed across social media platforms late on the evening of September 13. A fortnight later, speaking to The Telegraph over phone from Aligarh, close family friend Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi says, “Unlike his elder brother Anjum Quder, Kaukab sahab never used the honorific ‘prince’ before his name.”

Rezavi is a professor of history at the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). His father had been a friend of Quder. He continues, “I knew Kaukab sahab more as a lecturer of Urdu. He was a very simple man who would always be dressed in Lakhnavi style kurta-pajama and a sherwani that he would leave unbuttoned.”

Quder was born in Calcutta, though it was the suburb Metiabruz that was his deposed ancestor’s adoptive home since 1856. Wajid Ali Shah and Begum Hazrat Mahal’s son, Bir-jis, arrived in Metiabruz from Kathmandu and this is where he was assassinated. His wife, Mahtab Ara Begum, fled the place and gave birth to their son, Meher, in their Calcutta home. And this is where Meher raised a family with Mehdi Begum, and where Quder too was born.

Quder was sprung off the soil of Bengal, but what defined him was his legacy connection to Awadh whose core was and remains Lucknow. The house in which he lived the last 27 years of his life after he retired from AMU, the house where he was born and where he had wanted to die but couldn’t, is also known as the House of Awadh.

“That he was from Lucknow was apparent from the smallest of things,” says Rezavi. “He was a connoisseur of paan,” adds Kalbe Sibtain over the phone from old Lucknow. He continues, “Whenever he came to Lucknow, he would have paan from the shops near Ajmeri gate.” Sibtain is the younger son of Kalbe Sadiq, one of the patriarchs of Khandan-e-Ijtihad, a powerful old family of Shia scholars and jurists. Kalbe Sadiq was a dear friend of Quder and the two are also related by marriage. Quder’s wife Badrunnissa was born into Khandan-e-Ijtihad.

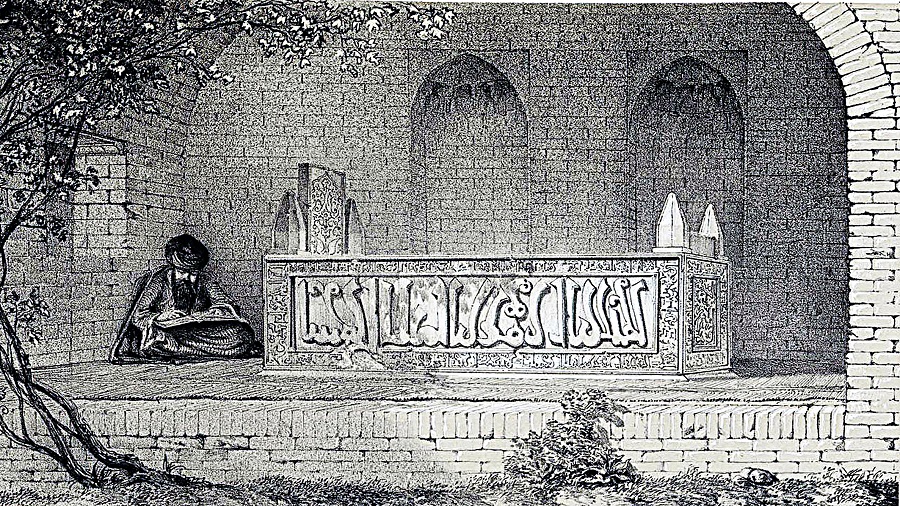

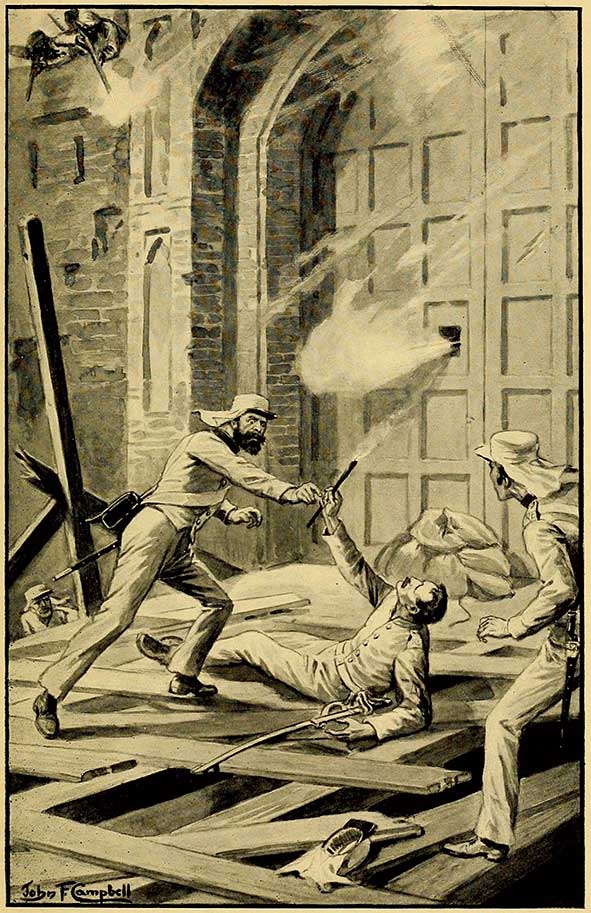

A scene from Satyajit Ray’s film Shatranj Ke Khilari, wherein Nawab Wajid Ali Shah meets General James Outram, the British Resident of Lucknow. Outram handed over to the Nawab the document of abdication from the British governor-general Sourced by the Telegraph

Others who knew Quder recall how he carried around his paan dibbi and batua, or money bag, all the time. And he practised the Lakhnavi zubaan. Says Sibtain, “Kaukab sahab lamented that the Urdu zubaan was losing its mithaas.”

Rezavi shares an anecdote from his student days. He says, “I would often travel on shuttle trains, a cheap medium of transport. One day I spotted Kaukab sahab in one of the compartments. He was standing in a corner, clutching at his file. When he spotted me he started a conversation about Urdu poetry. He was oblivious to the surroundings, to the crowd, to the fact that he was having to stand for all three hours of the journey from Delhi to Aligarh.”

Before he left for AMU to do his research on Wajid Ali Shah, before his LLB from the Calcutta law college, before he did his master’s in political science from Calcutta University, Quder was a student of economics at St. Xavier’s College, Calcutta. Golam Momen, his batchmate from college, recalls, “He was the secretary of the Urdu Literary Club. He was very well-read and was always trying to dig up things about his forefathers.”

Quder was reconnected to Lucknow when he married Badrunnissa. “It was providence,” says their youngest daughter Manzilat Fatima. “Most of his research work happened after he got married. He would go to the libraries in Lucknow, meet with locals and experts there,” she adds.

Quder has three Urdu books to his name — Intekhab-e Wajid Ali Shah (Selected writings of Wajid Ali Shah), Wajid Ali Shah ki Adabi aur Saqafati Khidmat (The Literary and Cultural contribution of Wajid Ali Shah) and Iqleem-e Sukhan ke Aakhri Tajdar (King of the Literary World). Manzilat says, ever since she can remember, her father has been very focussed on presenting the “truth” about Wajid Ali Shah. She says, “He would keep telling us that accepted beliefs such as the one about the Nawab having been exiled — he was actually arrested — that he was debauched and unfit to rule was history as told from the British point of view. He would talk to us about his findings — that the Nawab was an artist, a scholar; that Hazrat Mahal played more than a cameo in the resistance to the British, the fleeting mention in the history books notwithstanding.”

Dr Sudipta Mitra, who is the author of the book Pearl by the River, which is about the last decades of the Nawab, met Quder several times during the course of his research. Mitra says, “He was the only person who knew about Wajid Ali Shah.” He describes Quder’s study full of books. There were apparently books written by the Nawab in his collection. Adds Mitra, “He would read and translate from those. Satyajit Ray knew of his scholarship and that is why he reached out to him while making Shatranj Ke Khilari.”

Manzilat says, “We have not read his works on Wajid Ali Shah simply because even we do not know so much Urdu. But my sister is now planning to translate the book into English.”

Quder might have been born into a grand legacy, but according to Manzilat and every other person The Telegraph spoke to, he never flaunted it. She reads out from one of the letters he had written to Ray in 1976.

Quder writes, “If I happen to be a descendant of Wajid Ali Shah and a political pensioner for that reason, that is a fact over which I have no control. Otherwise, you will be sadly disappointed if you see in me a semblance of his versatile genius or even of his affluence. I am a poor man indeed, Mr Ray, and I was fortunate in securing a job of a university lecturer, not professor, mind you, largely because of an objective and dispassionate study of Wajid Ali Shah spread over 500 pages.” Quder was the last of the political pensioners of the Nawab.

So far what we have of Quder is this — introvert, self-effacing, Urdu scholar, historian, proud descendant. Manzilat now gives us a glimpse of the man beyond those particulars. Quder was fond of billiards. He was not only the founder-secretary of the Billiards and Snooker Federation of India, but also of the West Bengal Billiards Association and the Uttar Pradesh Billiards and Snooker Association.

Keen to pass on the love for the game to his daughter, he started to coach her. Recalls Manzilat, “From the time I was tall enough to reach the billiards table he started teaching me. He would take me on bicycle to the boys’ hostel at night. The common room used to be empty at that time and he could tutor me without any interruption.” He encouraged her to participate in the junior national snooker championships in 1980 and was delighted when she became the first woman participant of the national snooker championship.

Her bereavement is fresh, but Manzilat’s fond reminiscing tumbles out, breathing life into the portrait of a man little known.

She talks about Quder’s innate sense of decorum. “No sitting cross-legged in front of him. No serving a glass of water without a tray. No leaving the dinner table without his permission,” Manzilat rattles off. She says plaintively, “Days after he passed away, my cousin corrected me when I said — ‘Khana ban gaya hai’. She said, “Bawa hote to bolte, khana banaya nahin jata hai, khana pakaya jata hai... He would have said you cannot make food, you prepare it.”

Kaukab Quder had wanted to die in the House of Awadh, his home in Metiabruz, in the room where he was born. But when he contracted the coronavirus, he had to be hospitalised and it was in the hospital that he breathed his last. However, he was buried according to his wish, at the royal burial ground at Metiabruz, which is called Gulshanabad.

And while Manzilat is grateful for this wish fulfilment, it is another memory that comforts her now. In 2016, she had occasion to accompany her father to Lucknow for the screening of a documentary on Begum Hazrat Mahal. Says Manzilat, “We knew this was most likely the last time Bawa would get to be in Lucknow. He had wanted to see Chhatar Manzil, the Nawab’s palace. When we entered, someone senior from the Archaeological Survey of India came forward, greeted us and thereafter told the caretaker, ‘Yeh chaabi inki hai. Yahan jo bhi hai yeh inka hai. Yeh jahan bhi jana chahe inhe le jao... These are his keys. This place is his. Don’t stop him.’” Adds Manzilat, “They opened the main gate and he entered. Not only was he in Lucknow, he was also home.”