What China and India Once Were: The Pasts That May Shape the Global Future, Edited by Sheldon Pollock and Benjamin Elman, Penguin Viking, Rs 799

Science

The authors of this chapter – Benjamin Elman and Christopher Minkowski – have tried to see, with extreme circumspection and politeness, if the claims of India and China in respect of ‘Science’ hold any water.

Their conclusion is watery and they dodge what is known as the big Needham Question -- to use his own words -- “the essential problem is why modern science had not developed in Chinese civilization (or Indian) but only in Europe.”

They provide an answer obliquely by devoting almost the entire chapter to how both sets of rulers preferred astronomy and calendars to other things. The details of this preference are fascinating but the overall conclusion is quite disappointing. At least where science is concerned, neither India nor China amounted to much.

The industrial revolution in England from the mid-18th century onwards left India and China far behind. Before that they were the largest producers of goods and services in the world. Now in the 21st century they are once again regaining their lost positions.

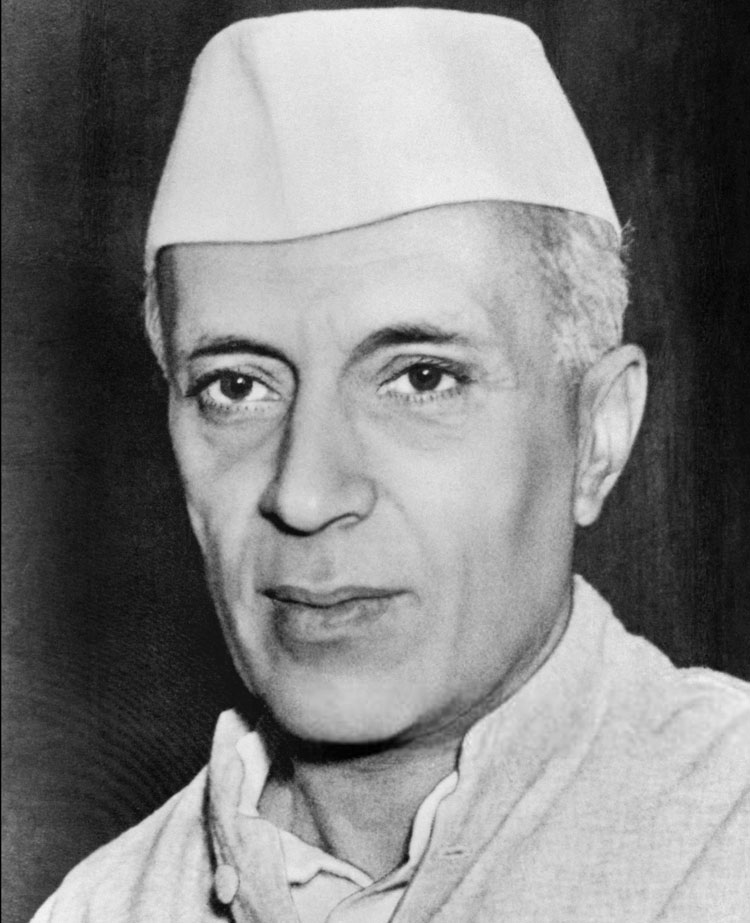

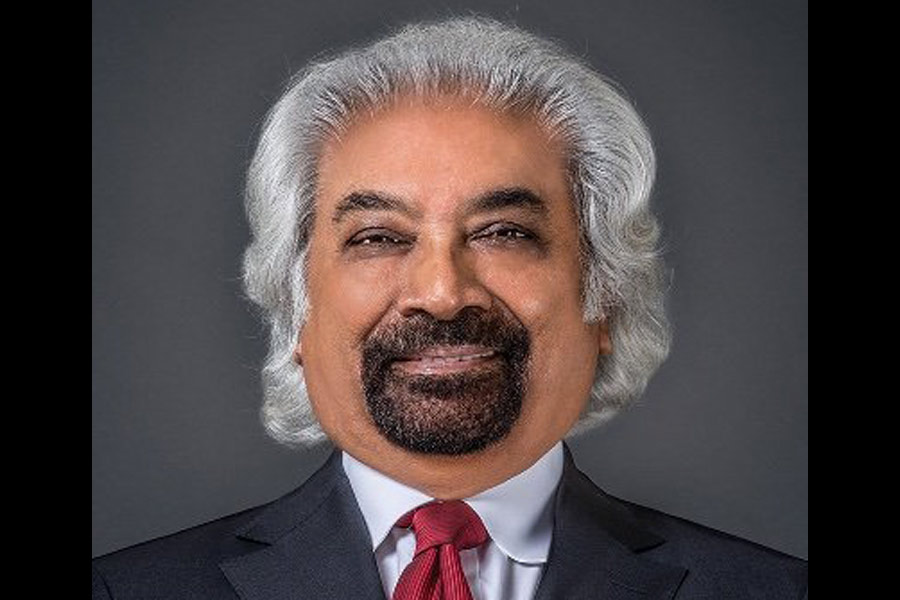

In this volume What China and India Once Were: The Pasts That May Shape the Global Future, Sheldon Pollock, a respected scholar of Indian culture and Benjamin Elman, a noted expert on China, have gathered together 18 scholars to tell us what India and China were really like before the West overwhelmed them in the 19th century and made them forget their pasts by imposing its own preferences on them.

Pollock and Elman have tried a unique experiment in the eight main essays that comprise this volume. Each essay is written jointly by an Indian and a Chinese scholar.

What emerges, although not very easily accessible to the lay reader, is a veritable feast of information and analysis. It is, in that sense -- after due academic care has been taken to define everything with as much clarity as possible -- an exemplar of comparative analysis.

Peas of a pod?

The two ruling dispensations in the period under consideration were the Mughals in India and the Qings in China. Both were outsiders. The Mughals came from Central Asia and the Qings were Manchus from Manchuria, a minority ethnic group in that part of the world.

It is extraordinary the extent to which between 1600 and 1900 both followed similar trajectories. Territorial conquest was, of course, a crucial element of their policies but so was the devising of new arrangements for governance whose objective was to extract wealth by taxing the farmers.

A large portion of the taxes were used for maintaining an army but, despite having a huge coastline, neither paid much attention to the navy. In the end this proved their undoing when the English arrived.

Both were dependent on military subalterns who eventually claimed limited sovereignty. The fragmentation this led to made it easy for foreigners to conquer the two countries. Both never developed their civil governments to the extent that their large populations required. This left them perennially short of revenue.

They, therefore, permitted foreign merchants who soon extracted concessions in return for the capital they brought. Over time, this altered the basic structure of their economies with their coastal areas getting integrated with European economies.

Eventually, this dichotomy between coast and hinterland caused their decline and downfall. As the authors of this essay – Pamela Crossley and Richard M Eaton -- on politics and government put it “neither empire developed a national style of rulership or a narrative of successful opposition to foreign intrusion that would have made them appear authentic to their subjects”.

In short, both lost legitimacy.

History

The two other topics of interest, to me at least, were history and science in India and China between 1600 and 1900. Neither presents a very edifying picture.

Where history is concerned, both approached it as an exercise in biography writing, the subject, of course, being the ruler. Thus, almost the entire exercise became a competition into hagiographies – almost because there were the odd persons who took a different approach and were either ignored (India) or put to death (China).

What does stand out is the obsession of rulers in both countries to control the narrative. But Indian rulers were far less paranoid than their Chinese counterparts even though they were far less powerful. This persists in both countries.

It must also be added that that post-1950, unlike in China, India’s much treasured tradition of independent journalism is providing future historians with an alternative source of history.

There is one striking feature that the authors – Cynthia Brokaw and Allison Busch – do not touch upon. This is that unlike in Europe where history is the tale of progress in the welfare of the people both in India and China there is a deliberate attempt to portray a Golden Age somewhere in the distant past. How this could have been has never been obvious.