The political, colonial, imperial debate around the peoples and the map of India that are the constant surroundings and backdrop to the lives of the British individuals described in The British in India is not the subject of this masterly social history. Instead, it gives us a clear view of individual British expatriate lives and experiences in and of India for good and ill through the centuries, from not long after the death of the first Queen Elizabeth well into the lifetime of the second. It may also explain the feeling for India of those who lived and worked there that has continued to pass down the generations in Britain. As for that fractious political debate, David Gilmour accepts there is “little hope of a consensus”. He gives the last paragraph of his book to a speech by Manmohan Singh at Oxford in 2005 that began: “Today, with the balance and perspective offered by the passage of time and the benefit of hindsight, it is possible for an Indian Prime Minister to assert that India’s experience with Britain had its beneficial consequences too.”

When the Maharajah of Jaipur visited Kedleston, Lord Curzon’s Derbyshire home, at the time of the coronation of Edward VII and watched rabbits on the lawn “gambolling in the sun”, he wondered why English sahibs did not “stay at home and play the flute?” Very few of the sahibs whose lives are explored in this marvellous book expected to return to a house like Kedleston. But what were the expectations of those who chose to go to India and those who were compelled to during 300 years of British trade, conquest and empire? For the latter, most visibly the private soldier, Kipling’s Tommy Atkins, the answer is simple, he had to take what came. For the former, wealth and adventure? Occasionally, they found either or both but the rare nabob’s fortune of the 18th or early 19th century was balanced against generally small rewards for individuals and by the difficulties, dangers and loneliness they and their families often suffered. The reader cannot help but also ask, why did they go?

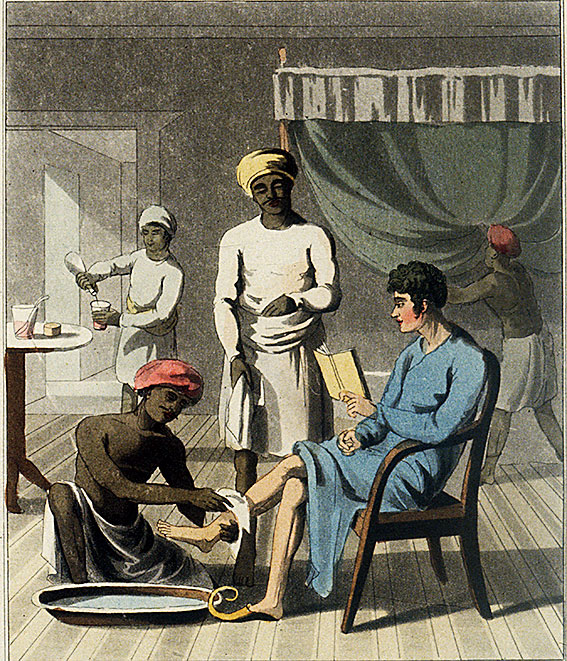

A print from 'The European in India' by Charles Doyley [Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Their motivations, reasons to leave, return or stay on; how and where they lived and worked; the pains and pleasures of family life are all chronicled in The British in India, a deeply researched and beautifully constructed jigsaw history in which the ordinary and sometimes less ordinary, George Orwell, Vivien Leigh, E.M. Forster, Kipling, make up the pieces. The fabled fortunes of empire accrued to very few. Some arrived with a dream of working “for the good of large numbers subject to his administration”, others because there was a job available, a chance for an outdoor life, or better prospects. Tommy Atkins was mostly bored to death and certainly to drink by the monotony, heat, and pointless parades of barrack life. But there were compensations in relatively decent pay and an Indian servant who might shave you while you slept before reveille.

There were often family obligations to motivate a young man to service in India, or, in due course, a tradition to follow among families who served in India generation after generation in military and civil service positions. For women as well from the late 19th century there were more opportunities and openings than talk of the so-called ‘fishing fleet’ of girls arriving from Britain during the cold weather to hunt for husbands would suggest. They came as nurses; Mrs Pack arrived in Bombay as early as 1715 to be the first matron of a British hospital in India; as doctors, teachers and the inevitable missionaries, all their numbers growing during World War I.

By then more than a century had passed since the memoirist William Hickey had survived his ‘rackety life’ in Calcutta against all odds to retire to dull provincial Beaconsfield. His Indian mistress had died in childbirth, their son shortly thereafter. Sudden death remained a constant in India throughout, especially among children, which is why those who could sent their children back to school in Britain. British life in India was always associated with loss, longing and homesickness, but for those who survived into retirement, the return ‘home’ was not easy either. Repatriates found they did not fit. India had burned into their senses, however problematic their lives there had been. Nostalgia for the damp green hills of home was replaced with a yearning for the warmth, smells and sheer scale of the country they had left behind.

The British in India: Three Centuries of Ambition and Experience By David Gilmour, Allen Lane, Rs 999