Book: Travellers In The Third Reich: The Rise Of Fascism Through The Eyes Of Everyday People

Author: Julia Boyd

Published by: Eloitt & Thompson

Price: ₹ 999

Hindsight, Hilary Mantel had once remarked, “is the historian’s necessary vice.” Hindsight is also, to further Mantel’s argument, a virtue cloaked as vice, the proverbial field glass that clears up for us, and not just for historians, the fog over tumultuous historical events. Moreover, hindsight’s power transcends that of a viewfinder. By providing an analytical framework to critically examine history, especially its fault lines, it grants us the ability to forestall history’s repetition as tragedy.

But what of the people — the ruler and the ruled — who are denied this tool necessary for judgment? How, for instance, did people in Germany — residents and visitors — view the cataclysmic events unfolding around them in the period between the two Great Wars? Were they able to anticipate the disaster that the führer and his henchmen were herding the nation towards? Does their ignorance make them complicit in the unparalleled crimes that the Nazis perpetrated on humanity?

These are compelling, but also complex, questions. Julia Boyd, who has spent years in post-War, Cold War Germany, attempts to answer them by assembling a wide range of perspectives by gleaning through hitherto unpublished archival material, such as letters and diaries, of those who visited Germany from the twilight years of the Weimar Republic till the end of the Second World War. The eclectic nature of the respondents — royals, celebrities, Quakers, writers, academics, Boy Scouts, sportsmen and sportswomen, journalists, diplomats, Afro-Americans, students and so on — lends to Travellers in the Third Reich its narrative richness and depth.

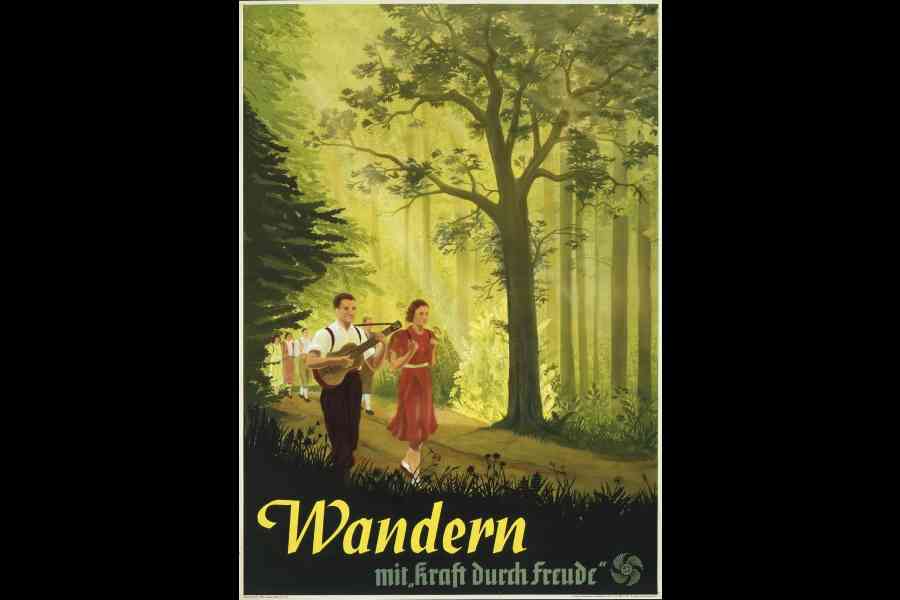

Hitler, expectedly, casts his long shadow on these pages: his interviews with a wide range of people, reveal his pathologies and, often, his undeniable pull on the interviewer. But what is even more interesting than these tête-à-têtes with Hitler are the polarised views that his reign generated. Apologists of the Nazi regime — there were many and they straddled different nations, ethnicities and social classes — viewed the times and lives through the lens of delusion, affinity or self-advancement. Philip Conwell-Evans, a British academic, observed the barbarism of the burning of books with deplorable equanimity; Sir Arnold Wilson, a parliamentarian, basked in the “energy” unleashed by National Socialism; in 1939, Thomas Cook published a brochure for people to experience ‘New Germany’. Cynicism and resistance were equally robust and heterogeneous in terms of demographics. Not everyone fell into the trance that was Nazi propaganda: the African-American academic, W.E.B. Du Bois, who was in Germany during the Berlin Olympics, ridiculed those visitors who returned convinced that Hitler’s Germany was a “thriving”, “efficient” and “friendly” nation. Surprisingly, this clash in perspective was evident even after Hitler had lit the flames of war. Thus, Sven Hedin, the feted explorer, didn’t mind lunching with Göring on “[b]utter, real Gruyere cheese, caviar, lobster…” among other delicacies at a time when a more realistic picture of a war-ravaged nation was being written about by anti-Nazi American journalists.

Boyd must also be credited for remaining objective — fair — in the face of history’s quirks. She does not exclude voices and their chroniclers that echo the deep disenchantment with the humiliation heaped on Germany by the international fraternity after the conclusion of the First World War. The ogre called Hitler fattened itself on this collective anger.

Despite its exhaustive material, what makes this book engaging is Boyd’s ability to test our moralistic presumptions about history’s acts, actors, and audience. Consider the dilemma faced by those who loved Germany for the magnetic pull of its landscapes and culture and continued their visitations: “The war had created despair among Germanophiles not only because of the human tragedy but because it had cut them off from such a significant part of their own lives. It was not that they were insensitive to Nazi horrors but they clung to the hope that Hitler would quickly fade and their Germany — the real Germany — would re-emerge…” Can the modern reader afford to dismiss this wish as a testimony of agnosticism or, worse, indifference? The confusion attendant to the rise of National Socialism is, in the same vein, laid bare by Boyd. In the early 1930s, even a sophisticated political consciousness, Boyd shows, found it difficult to comprehend whether, for instance, socialist principles couched in idealism were endemic to dictatorship. Or whether the mushrooming labour camps were an edifice of experimentation or extermination.

There can be no ambiguity about the evilness of Nazism and its principal agent. But the men and women who observed — analysed — that spectre, its patrons, its critics, were also integral to the historical conditions that coloured their judgment. An objective appraisal — praise or condemnation — of Boyd’s ‘Everyday’ witnesses of Nazism would not be possible without an acknowledgement of the zeitgeist.

This brings us back to hindsight. The astounding literature on totalitarian polities — Boyd’s book is a significant addition to this body of knowledge — should make us, the progenies of that history, capable of making an informed choice about the architects of modern autocracies, closer home or afar.