THE GREAT FLAP OF 1942: HOW THE RAJ PANICKED OVER A JAPANESE NON-INVASION

By Mukund Padmanabhan

Vintage, Rs 599

Idioms and parables warn against the dangers of believing in rumours and acting hastily. One wonders if the people living in cities along the eastern seaboard of the Indian peninsula, including the officials of the raj to whom the responsibility of ‘ruling’ the natives was entrusted, stopped to think about those teachings before fleeing in mass hysteria during the Second World War. Decidedly not, readers of Mukund Padmanabhan’s The Great Flap of 1942 would say; and they would be right.

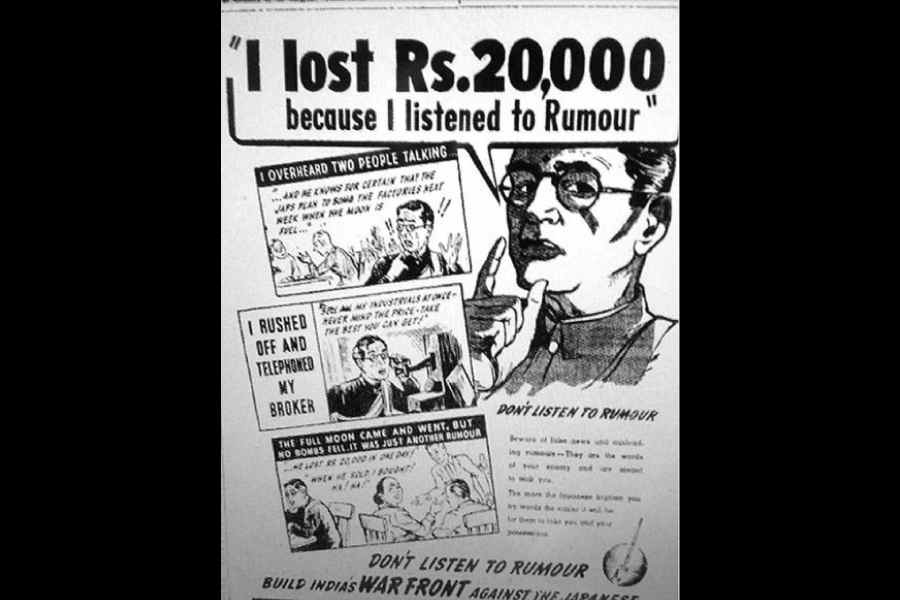

Padmanabhan’s account deconstructs, piece by piece, the chain of events which led to the large-scale evacuations — sometimes forced, sometimes voluntary — of cities like Madras and Vizagapatam (referred to as Chennai and Visakhapatnam, respectively, today) as conflict ensnared almost the entire globe in its web. Apart from a detailed, multi-chapter explanation of the creeping advances of the Japanese armed forces through British ‘territory’ — starting with the attack on Kota Bharu, which saw “the first ground battle fought between Japan and the Allied forces in World War II”, and escalating with the meek surrender of Singapore, supposed to be an impregnable British fortress — that set alarm bells ringing through the raj’s corridors of power, there is also considerable discussion on how the Indian freedom struggle reacted on finding their colonial rulers weakened. Even for readers who are aware of Subhash Chandra Bose and his decision to align with the Japanese to further anti-colonial interests, the divisions within the Congress on how best to take advantage of a Britain on the back foot, supplemented by numerous citations from newspapers like the Statesman, The Hindu and Amrita Bazar Patrika, make for absorbing reading. Eventually, even the shoddy, bungled evacuations were rendered unnecessary. Apart from an aerial assault of Vizagapatam and Cocanada (Kakinada) by a fleet led by the formidable Jisaburo Ozawa in April 1942, peninsular India remained out of reach of the Japanese.

In addition to being a treasure trove of illuminating sketches — revelations of racial discrimination against Indians even in the evacuation of civilians from Southeast Asia and furious proclamations by British officers about how “Indian politics was an assembly line for the production of fifth columnists” — what makes The Great Flap stand out is the author’s scholarly meticulousness in documenting the sources. Every claim is scrupulously corroborated, every fact verified. Let us hope more such accounts of lesser-known events are written instead of saffron reimaginings of history.