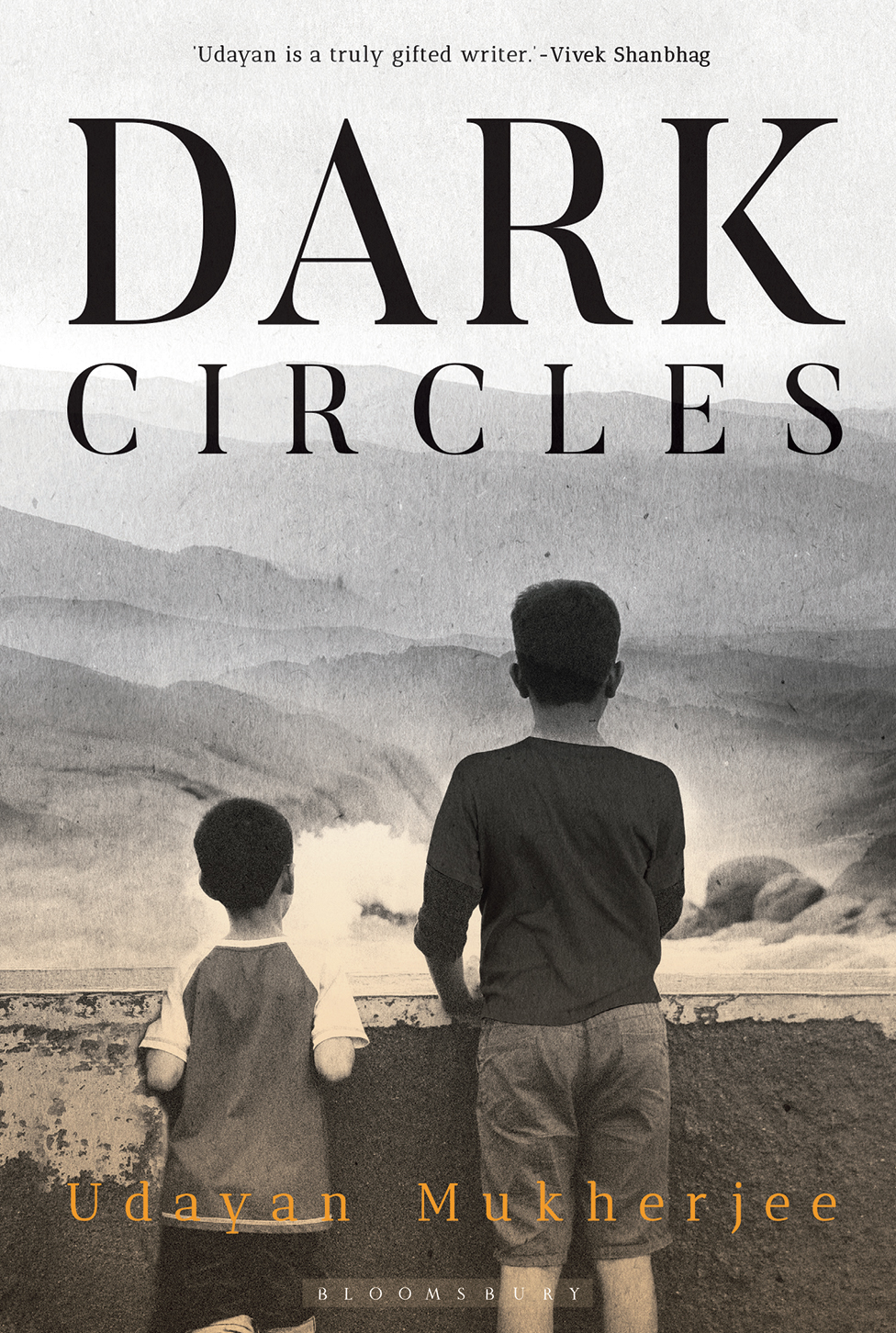

Dark Circles by Udayan Mukherjee raises questions about the very idea of “family” as we know it. The story starts with a letter from a mother to her grown-up son delivered after her death, a letter that leaves a trail of devastation in the lives of her two sons, Ronojoy and the younger Sujoy. Yet it is with this missive from the beyond that the two men must begin the process of healing their scars of childhood. Taking a severely unsentimental view of marriage, family and parenthood, Mukherjee weaves a moving tale, told with a simplicity that is engaging.

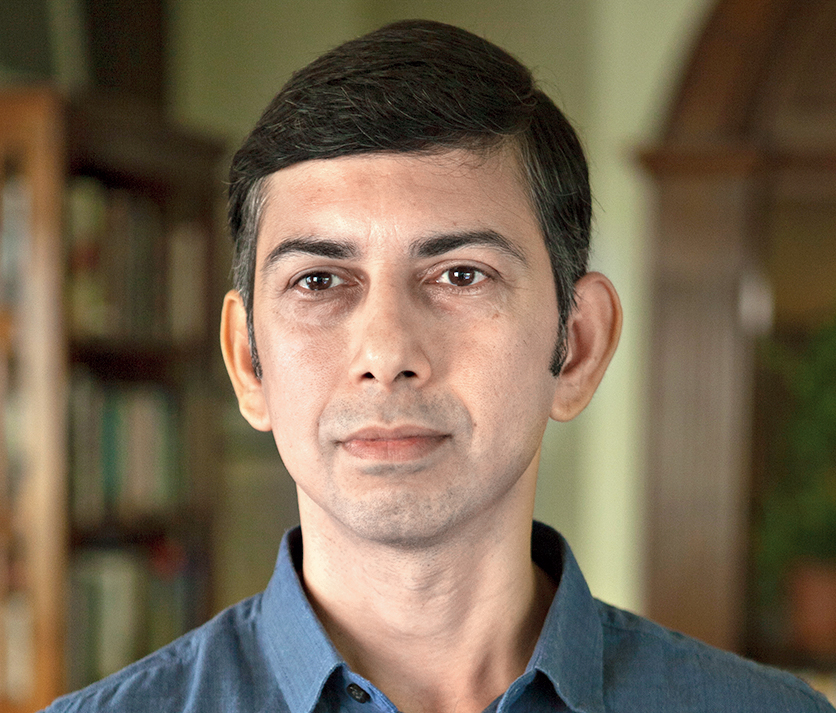

Readers might recognise Mukherjee from his days as a CNBC television anchor. After two decades in financial journalism, he quit the newsroom and headed to the hills of Uttarakhand, setting up a couple of luxury resorts. A former Calcutta boy — and the brother of acclaimed novelist Neel Mukherjee — he makes his foray into fiction with Dark Circles (published by Bloomsbury India, Rs 499). A t2 chat...

Congratulations on your debut novel. Did you always know you would write one, or did your decision of walking away from the television newsroom open up new avenues of expression?

For many years, I dreamt of writing a novel. But it wasn’t easy to get started on one. Initially, the pressures of a frenetic television job crowded out the mind space required to write seriously and later, I didn’t feel I was ready. The idea was never to write something and get published because it could be done. I love reading literary fiction and the novel can never be a frivolous pursuit, in my eyes. But then, slowly, the pieces fell into place. I quit my day job, moved away from the pace of Mumbai, met interesting people, roamed around in unfamiliar terrain and, crucially, found myself spending a lot of time alone. I took a few baby steps at writing, then a few more and before I knew it, I was hooked. I lay no claims to having produced a good book but it was a consuming and immersive experience for me.

Who do you imagine is the reader of this book?

I wanted the book to be accessible. While conceding that I am relatively new to this game, I disagree with conventional norms of what qualifies as ‘literary’ versus ‘commercial’ fiction. Nor do I agree that a novel needs be dense or mildly inaccessible to demonstrate its literary merit. To me, that is intellectual snobbery.

Rather, I feel that a novel should lend itself to various levels of interpretation. Incredible layers of complexity can be conveyed through a seemingly simple narrative. That is how the world works — through a simple set of actions or words, prompted by the most complex of motivations. That is the way I saw the novel; as a perfectly plausible set of events in the life of a family, under which run very deep currents. I did not want to exclude a reader, any reader, from being able to read it as a story. The depth to which she is able to access the characters and the intended emotional scaffolding, rests on the author’s ability to convey what simmers below the surface and her own sophistication at deciphering nuance.

In this, my guiding light is Satyajit Ray. His films had incredible depth yet anyone could watch them and enjoy them. He was accessible yet complex, in that lay his greatness. I could never write a book aimed at a handful of “elite” readers, to the exclusion of all others. Someone could point out that it may be because I lack the refinement for it, and I am prepared to accept that.

A family torn apart by a terrible secret sits at the centre of Dark Circles. How did the germ of the idea come to you?

Families often nurse grave secrets. This is how it has always been. If our grandparents and parents could speak openly about what they experienced or witnessed happening in families known to them, it would shock us. The truth was discreetly swept under the carpet, so that the illusion of acceptable morality was not shattered and people could carry on with their lives. While Dark Circles is not borrowed from an actual event in someone’s life, no part of the story has not happened in the real lives of families. I am convinced about that and believe it will not strain the credulity of readers. My intention was to present readers with a morally grey narrative and push them to ask where they stood on questions of propriety, morality and judgement. I wanted them to feel uncomfortable, as that is how I felt while I wrote the book.

Family is usually thought of as “a happy place”, associated with warmth, love and security. You’ve turned that idea on its head with this book…

I don’t subscribe to the illusion of the happy Indian family. It can be a place of security and warmth, but more often than not, I believe it is a dark place. A bed of manipulation, deception, repression and suffocation. The chains that bind us to family sometimes lie in the past and sometimes in the present. We are all so conditioned to believe in the myth of the family that we embrace denial to be able to deal with it. But sooner or later, we fail and then the ugliness pours out. The catalysts of this failure vary, from money to control or even lust. Most of us understand this and I wanted to probe the dominant emotional currents of the novel within the construct of a family setting.

Mental health is a recurrent theme. It is heartening to see Ronojoy seek help and implore his younger brother Sujoy to get help too…

Depression and mental health are a very important part of this novel. It is all pervasive in the society we inhabit, yet very few people are willing to talk about it. Yes, there is a greater awareness about it today but it is only in cases of advanced dementia or schizophrenia or bipolar disorder that people seek medical intervention.

There are millions of people who suffer from some degree of mental illness which, while not fatal, is enough to destroy their lives, careers, relationships and emotional balance. There are too many unanswered questions — what triggers depression? Can it be inherited? Is medication the cure? The subject intrigues me and while the novel is not meant to engage with it at a clinical level, it certainly does so at a psychological plane.

Agency picture

You spend most of your time up in Uttarakhand now, gazing at the Himalayas. In this book, the characters often return to the house in Mukteshwar, where you yourself have a home. Was that a conscious decision or did your own love for the mountains seep in?

I love the Himalayas, always have. In the novel, across generations, the mountains are a refuge, from all that can and does go wrong. When people are hurt, they seek shelter and comfort. Sometimes, they turn to family but when it is the family that is the cause of hurt, they turn inward. Finally, difficulties have to be resolved inside one’s head though one can be successful or not, at it. This is the reason the Himalayas play such an important role in the book; not just to provide the topographical relief of a picturesque setting but to probe this interiority. The novel is not factually autobiographical, but in how the protagonists feel about the mountains, there is a great resonance with the author.

What kind of a reader are you? Tell us about your literary influences…

I love literary fiction and crime fiction. I am not wedded to any particular style of writing though I hugely admire the sheer beauty of the prose of many Irish novelists such as William Trevor, Calum McCann and Colm Toibin. Among American novelists, I love James Salter, Marilynne Robinson, Philip Roth, Richard Yates. Graham Greene is an old favourite, as are John le Carre and P.D. James. Javier Marias is incredible. But then, it is also about individual books, not novelists.

John Williams’s Stoner is outstanding as are Per Petterson’s Out Stealing Horses and Reunion by Fred Uhlman. I think Mohammed Hanif is the brightest star from Pakistan. These authors can often say in a sentence what I would take a hundred pages to express, and fail even then. My heart brims over when I read them and my head is bowed in admiration. That is one thing about being an aspiring writer — the moment you delude yourself into thinking you have written something wonderful, all you have to do is turn over a few pages from a truly great novel.

Having been a part of the manic TV newsroom, will we see you mine those experiences in a future novel?

Not really. That world bores me. But it’s an interesting question as almost everyone I know thought that my novel was either about the financial markets or the world of television. Perhaps because it is the world I know. Even publishers wanted me to write non-fiction, presumably about the business world, or at least a corporate thriller. But that is exactly what I would never write about, not least because it is the expected thing to do and thus terribly predictable.

After 20 years of doing something, you enter a comfort zone and to do something even half good or original, you have to step out of that and challenge yourself. Else, all you are doing is some kind of rent seeking for having put in all those years. So, no stock market books, no books on the Indian economy or the corporate sector, ever for me. All that would achieve is book sales and a bit more money, and that is not the reason why I write. I have paid my dues at the altar of the money goddess, now I must tend to my soul or whatever’s left of it. It may be ambitious but they say that a man’s reach must exceed his grasp, don’t they?