For ages, trees, alone or huddled together as forests, have stood firm in the literary world, but mostly as peripheral scenery or accessories of narration. At other times, they have featured as havens for the persecuted, whether as the Sherwood forest of 17th-century England or the woods in Toni Morrison’s Beloved where the slaves flee for refuge. But the anthropocentric human mind has seldom seen these silent sentinels of the natural world for what they truly are. Long before the genre, climate fiction or ‘cli-fi’, came into being — the term was coined in 2013 and is used retrospectively to classify works about environmental degradation — fantasy made room for the forest ecosystem. J.R.R. Tolkien — he died this month in 1973 — not only welcomed the real-world flora into his fiction but also created over 20 different fictional plant species, ranging from full-grown trees to shrubs, herbs and weeds, besides many other wondrous forest creatures. Whether it is the magical White Tree of Gondor or the pair of enormous, luminiferous trees of Valinor, Tolkien imparts to each sylvan species its unique traits.

To care for the forests of this world, Tolkien created tree-herders: the Ents, one of the most ancient creatures that roam Middle-earth. Treebeard, their leader, seems “clad in stuff like green and grey bark, or... that was its hide”, with “a sweeping grey beard, bushy, almost twiggy at the roots, thin and mossy at the ends”. With time, these shepherds begin to look like the plants they tend. Timeless themselves, they have little understanding of the pace of other races: they come to a “hasty” decision at the end of a three-day long Entmoot — a meeting of Ents — to resolve action against Isengard, the fortress of the evil sorcerer, Saruman, who destroyed forestland entrusted to Treebeard’s care.

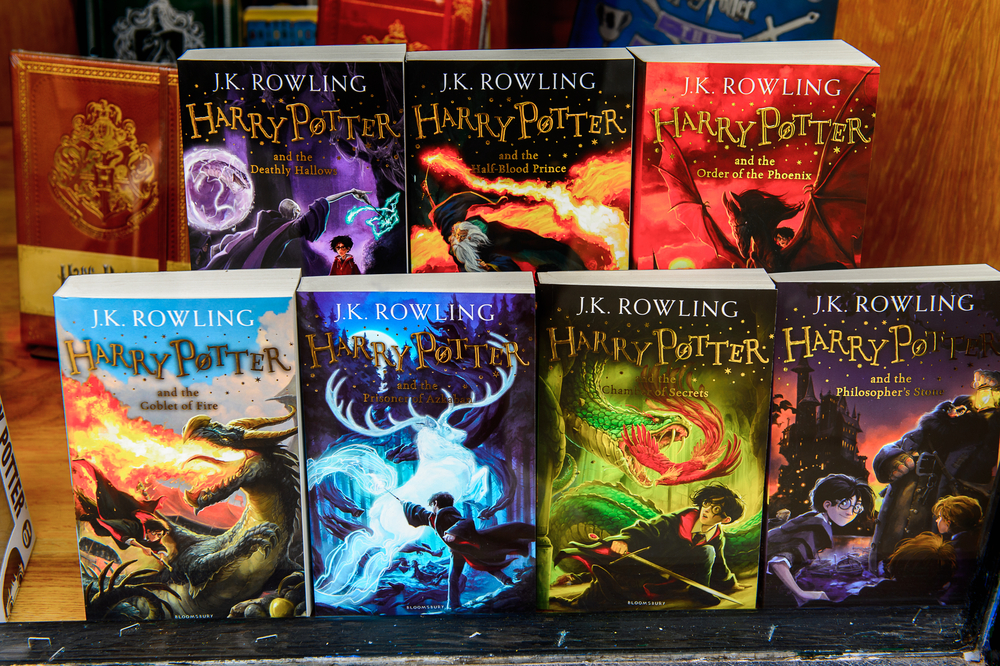

But once spurred into action, the Ents can resemble the Huorns, another tree-like species, albeit one that does not share the Ents’ amicable disposition — do Huorns not talk to most other races because they can’t or because they choose not to? Like the ghost tree in Sleepy Hollow or the frightful Forbidden Forests near Hogwarts, angry Ents are formidable: they crumple up the iron gates of Isengard like thin tin with a punch and tear up its rocks “like bread-crust”.

But the tree-lover in Tolkien refused to look at them as malevolent. He defended their case: “In all my works I take the part of trees as against all their enemies... Fangorn Forest was old and beautiful, but at the time of the story tense with hostility because it was threatened by a machine-loving enemy. Mirkwood had fallen under the domination of a Power that hated all living things but was restored to beauty and became Greenwood the Great before the end of the story.” Yet, as far as reading signs is concerned, mankind is even slower than the Ents. Are not burning forests and rising sea levels more obvious omens of doom than the woods marching towards castles ruled by callous men?