Syed Tahir Rufai Tahir writes in the Sufi tradition, which transcends the material world, seeks union in spirituality Sourced by The Telegraph

Basant Rath is in no mood to be talking poetry now, ‘I am too messed up in my head. Delhi is so heartbreaking’ Sourced by The Telegraph

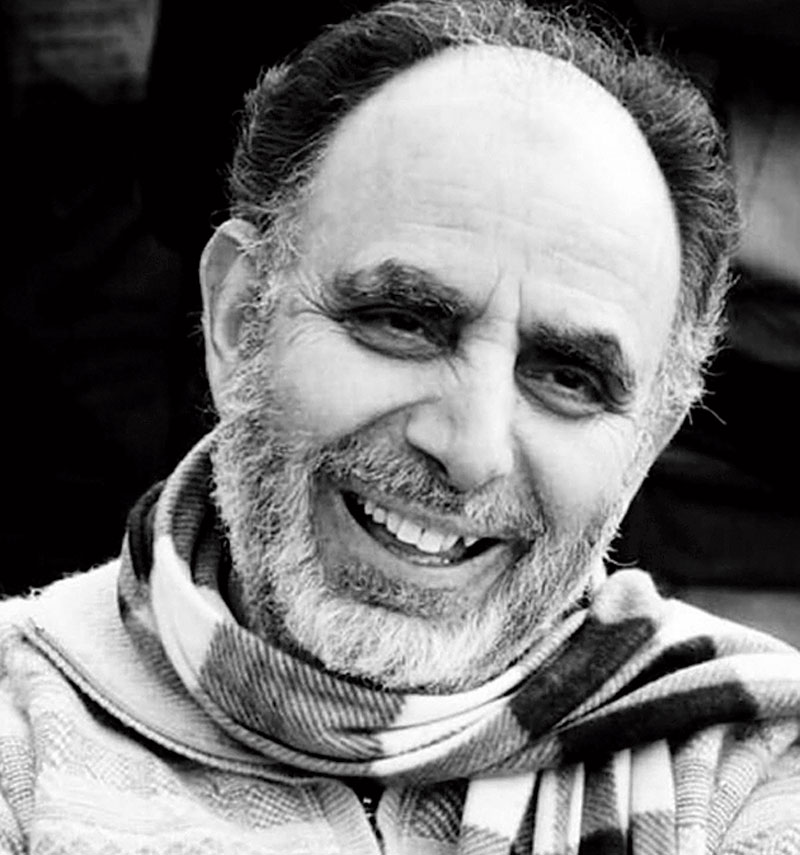

Ayaz Rasool Nazki says, ‘Sufism runs through our blood... It is the foundation on which our thought is built’ Sourced by The Telegraph

I’ve been in a cage for so long

I’ve fallen in love with it

This feeling growing strong

I forgot my beloved

I have to meet him

In those forgotten gardens

Where there is a forever

For eternity I sleep

Where he looks over me

And upon my cage

Which turns into dust

In a few beliefs

The composer of these lines is the 21-year-old Kashmiri poet, Syed Tahir Rufai. This is the very first poem in the anthology of poems, In The Name Of Mashouq, published this year by Ananda Lal. Mashouq means beloved. In Tahir’s poems the beloved is God.

Apart from Tahir’s poetry, Lal’s Writers Workshop has published works of two other poets from Kashmir — the trilingual poet, Ayaz Rasool Nazki’s Songs of Light, and police-poet Basant Rath’s Own me, Srinagar. If Nazki is the senior voice from Kashmir amongst the three, Rath is technically the “outsider” with a sympathetic voice, while Tahir’s is the fresh Sufi voice.

Lal says, “In each of their cases, because they were writing on Kashmir, no one may have wanted to publish them.” Tahir agrees it was hard to find a publisher, but he puts it down to the general disenchantment with the printed word rather than his Kashmir origins. “People are forgetting about books,” he says. But he concedes that this is not the first time Writers Workshop has published works of Kashmiri poets. He adds, “Well-known poets from the Valley including Agha Shahid Ali and Nazki have been published by them.”

In a recent interview, Nazki had said: “For writers writing in Kashmir and elsewhere, Kashmir has become intellectually a major handicap.” He elaborates on it to The Telegraph, “When a house is on fire, the entire attention is focused on the house on fire, no one can afford to look elsewhere — at the lawn in front, at the flowers, at the trees surrounding the house, the birds in those trees, the beautiful stream flowing. It’s the same with us. This fire has been limiting our horizon as creative people. I would love to creatively engage with beauty, life, aspirations and dreams, and the future.”

The fire has generated a genre of literature in Kashmir that calls itself resistance literature. Resistance literature, according to Nazki, is the artist’s way of dealing with a difficult situation, of making sense of it. Repression of human beings is always met with a response and that response can take any form. People engage in raw protest: they congregate, raise slogans, some pelt stones, some resort to more deadly forms of defiance. “As a poet, I can at best pelt my tormentor with words, with poems,” he adds.

And what is the life of such poetry? Nazki believes that that depends on the level of internalisation. And then again, art has to accompany craft. He says, “Literature lives long, much longer than the tormentor and the tormented. Such poetry and such art provide not only a historical memory, but also a landmark for inspiration for future generations. Many compositions that we have seen emerge over the years from Kashmir will live long.”

Talking about the Sufi tradition in Kashmir, Nazki says, “It runs through our blood, it pervades the air we inhale. It is the substance, the foundation on which our thought is built. Not only literature and poetry, its essence runs through the arts and crafts we are famous for. It is the basic matrix in all our motifs, in all the patterns that we weave and carve. Poetry of any genre in any language in Kashmir — many of our poets are multilingual after all — has the basic current of a mystical thought process flowing through it. Knowingly or unknowingly we use the mystical experience that has travelled to us from our forefathers.”

Nazki writes about the syncretic character of the poetry too. Muslim poets singing in praise of the Prophet and Hindu poets writing Krishna lilas. Haji Mohammad Abdullah Tibetbaqal, the maestro of Sufiana music, singing a eulogy to Shiva and Mohan Lal Aima, the iconic music composer, singing a hymn to the Prophet.

And what does something like the abrogation of Article 370 and the subsequent lockdown do to Kashmir’s poetic tradition? Nazki says it’s too early to speculate. “The situation is still of complete disbelief. ‘How could they’ is the dominant question. It will take some time for this to sink in and find a place to settle in.”

As of now, after all these decades of unrest and conflict, the question is of loss of identity, an address, an abode. These are now the issues that a poet has to grapple with. “Denying someone political or economic rights is one thing but wishing away a people, consigning them to nothingness is a different game altogether. I personally see it as being thrown into a void,” says the scholar-poet.

Agha Shahid Ali, who has become a role model for many young Kashmiri poets, saw Kashmir as a country without a post office. “But now, Kashmir,” says Nazki, “is in a wilderness without the Internet.”

The Internet just got restored, but that doesn’t make Kashmir any less a wilderness.

Tahir has been writing since he was 10 years old. He says, “I grew up in a family where everyone is into literature, dhikr (short prayers).” But he insists he does not read any poet for fear of being influenced. “I started reading Rumi’s Masnavi although my father had repeatedly told me not to. I read the first poem. It was about a flute which was carved out and separated from a tree and now singing sadly in remembrance of its beloved. It was too much for me to take. I closed the book and haven’t opened it since. When you find something so beautiful, you don’t care for the physical world anymore.”

Basant Rath has made news for his idiosyncratic ways of policing in the Valley and his sympathetic approach to the people there. As inspector-general of police (traffic) – Srinagar, he streamlined the chaotic traffic system in less than a year. He did not hesitate to arrest sons of politicians and bureaucrats caught violating traffic rules, thus endearing himself to the locals. After a public spat with the mayor, Junaid Mattoo, in 2018, he was transferred and is currently attached to the office of Commandant General, Home Guards. He moves around Srinagar in public transport without security; distributes books among the Valley’s young to help them prepare for competitive exams and during the early days of the clampdown and Internet ban, he offered his phone to people to connect them with their loved ones.

The sociology student from JNU has come a long way from Odisha, his home state, and quite literally too. Today, he considers Mandi in Poonch district his second home. The titles of Rath’s poems — Letter from Leh, Lonely Line of Control, Ode to Faiz Ahmed Faiz — speak for themselves. The one called Unmarked Grave reads: “No marble. No flowers./No traffic. No crowd./No fatal date engraved./Everything nameless/by force of habit./On this side of the Pir Panjal/we deny the dignity of death/to the one who dies in absentia./By force of habit.”

Rath, however, is in no mood to be talking poetry now. He apologises saying, “I am too messed up in my head. Delhi is so heartbreaking.”

Ayaz Rasool Nazki is possessed of a sensibility that is at once postmodern and traditional. The biologist engages with questions of identity, memory and aspirations. His style is minimalist. Sample this poem titled K is Poetry. It goes: I am not writing/any poem today/I am in the/Valley of Kashmir.

Says Lal, “Nazki writes about Kashmir and Kashmiris based on an entire life’s experience and (knowledge of) the local culture. His style is lyrical and often melancholic. Rath writes on what he sees around him as a police officer: people’s despair and the deprivation of the present moment; tragic and violent incidents that take place almost routinely. His poems are relatively more down-to-earth and realistic, but equally sensitive and sympathetic.”

Tahir has not long ago graduated in psychology from Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia and returned to Srinagar. What about the style of his compositions? Continues Lal, “He writes in the ancient Sufi tradition of short, pithy, suggestive verse, which transcends the material world and seeks union in spirituality. Why would a young college student want such an outlet? Obviously because things are not ideal in his world.”

Kashmir has a rich culture of poetry and Sufism. Says Tahir, “Sufi saints have come here. Many were born here and that has influenced the Kashmiri culture to a great extent. The most followed Sufi order here is Qadiri.” But he has a problem with his generation and its understanding of Sufism. He says, “My generation thinks Sufism is just about Mawlana Rumi, his poetry and dancing in white robes, but that is not all. That’s a speck. Major Sufi orders are Qadiri, Naqshbandi, Chisti, Suharwardi and Rufai, and very few of my generation know of these. Even Mawlana Rumi is believed to be from the Naqshbandi order.”