Book: The Living Mountain: A Fable For Our Times

Author: Amitav Ghosh

Publisher: Fourth Estate

Price: Rs. 399

Unless you have been living under a rock during these last few years (or have gazed long at your screen to the extent that the abyss has started gazing back at you), you’re likely to know that Amitav Ghosh’s latest work of fiction concerns the Anthropocene. The work was declared as ‘important’ even before the Northern machines pounding giant coniferous trees into woodpulp moulded the natural-shade paper that was folded between the covers of this pocket-sized, sleek, overpriced book. It concerns a climate “fable” spanning around thirty-five pages, and is sold under the name of an author who has earlier enthralled the climate-change-denying world with true “parables” in The Nutmeg’s Curse and initiated important dialogue about the “unthinkable” in The Great Derangement. However, as the publishers are wont to know, a short story sells better as ‘climate fiction’.

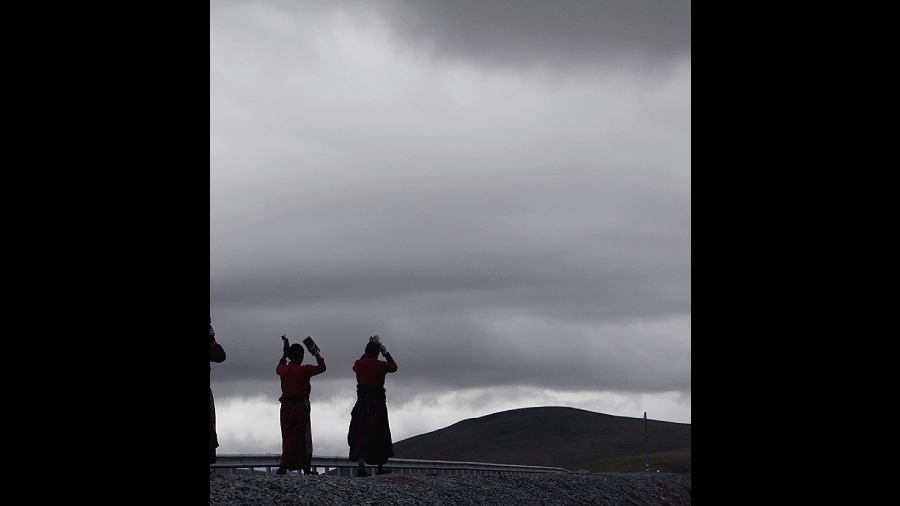

Ghosh’s Anthropocene “fable” — if we chose to ignore the meta-fictional device of this book being shared on an online reading group by a rather sad girl whom her confused therapist advised to write the story down — is “about some poor people on a remote island who suffer a terrible fate”. The narrator is another girl, a member of the ancient Valley People living next to the Great Mountain, Mahaparbat. Uncorrupted by civilisation and technology (albeit by virtue of a great portcullis that prevents outsiders from reaching Mahaparbat), these island people live their happy lives collecting nuts from the Magic Tree, singing and dancing; societal order is maintained by somber Elderpeople, and prescient Adepts who read the voice of the Mahaparbat through their feet as they dance. Soon enough, their happy paradisal world disintegrates with the appearance of strangers “from a land very far away” — a tribe of people who call themselves the Anthropoi.

Triggered by an unexplained, obsessive-compulsive urge to climb the Mahaparbat, the Anthropoi colonise the Valley People, and while passing rechristen them as Varvaroi. The Varvaroi refashion their societies and worldviews according to the manners of the Anthropoi, overcome their ancestral taboo preventing exploration of the mountain, and join the mad climb. Like an angry god waking from its slumber, the Mahaparbat rumbles and shakes; and as the Varvaroi overtake the Anthropoi and almost reach the summit, the shared world begins to crumble. The Anthropoi start blaming the Varvaroi for being overzealous with the climb; and they together realise that they have lost all contact with ancestral knowledge. The “terrible fate” of these people is left undisclosed as the story ends with a warning: a former Adept, now an old woman, reprimands the climbers for waking up to the realisation that the “poor, dear” mountain is alive. The woman cries, “How dare you speak of the Mountain as though you were its masters, and it were your plaything, your child? Have you understood nothing of what it has been trying to teach you? Nothing at all?” The narrative ends at this moment of incomprehension, while also suggesting a return to the uncorrupted wisdom of the ancients.

There are reasons to be sceptical about this imagined return though. From the start, we humans have been highly destructive as a species: long before the advent of European colonialism, during the millenia that followed the retreat of ice-sheets and the emergence of Pleistocene grasslands, our appearance as scavengers and hunter-gatherers across different continents has corresponded to the annihilation of almost all other major fauna — pinnacling in the years after Columbus with rapid advances in technology, commercial greed, fossil-fuel burning, and religio-political lunacy. Ancient societies cannot be totally absolved of altering the climatic course of the planet; according to the ‘Long Anthropocene’ hypothesis offered by the paleo-climatologist, William Ruddiman, we are inhabitants of a world where carbon dioxide levels began to rise some eight thousand years ago and dangerous spikes in methane levels began some three thousand years later, all due to the rise of subsistence-based agriculture and the accompanying deforestation (think Khandab-dahan in the Mahabharata), which started a chain of obliteration affecting a million other life-forms. At least, the debates aren’t over.

Moreover, unlike the stories and myths of indigenous peoples, which try to include the perspectives of animals, birds, fish and the trees (or, for that matter, later fables in the mould of Aesop that anthropomorphise them), the search for ancient wisdom in this modern “fable” operates under an indemnifying, exclusive foregrounding of hope and despair about the human condition: it shows no awareness of any birds and beasts co-inhabiting the Mountain; Adepts or Anthropoi, its characters are incapable of thinking beyond their species’ need for self-mythologisation.

In case you seriously want to undergo journeys into imaginative climatic futures involving compassionate wisdom of the ancients, skip this book. Try J.G.Ballard’s The Drowned World or Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home; you might find them long, politically-incorrect, but a lot more introspective.