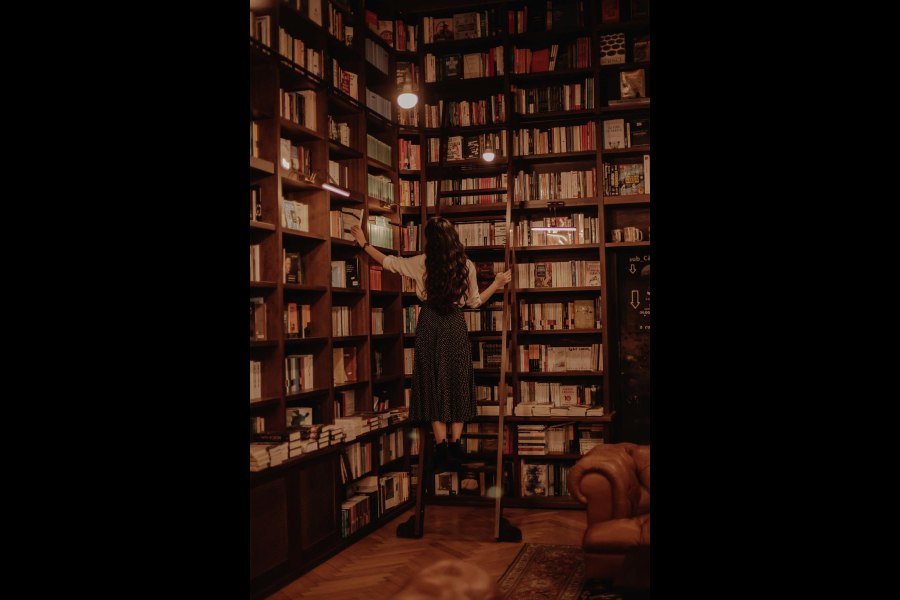

Book: WHAT YOU ARE LOOKING FOR IS IN THE LIBRARY

Author: Michiko Aoyama

Published by: Doubleday

Price: Rs 699

Humans are programmed to find an anchor in life; something that leads the way when life’s compass strays, keeping them grounded at the same time. For the five people in Michiko Aoyama’s book — translated from Japanese by Alison Watts — the anchor lies at the heart of the Hatori Community House in Tokyo — at the library, or, more importantly, with its middle-aged librarian, Sayuri Komachi.

Tomoka (21) undermines herself and is tired of her insipid life. Ryo (35) works a tedious job; nostalgic of the dream he had in high school, he repeats the pacifying hum of “one day”. Natsumi (40) finds herself replaced after 13 years of hard work and diligence at a job she loved even as she learns to re-adjust her life as a new mother. Hiroya (30) is skilful but unemployed and, hence, demoralised. Masao, for whom “retiring from work is the same as retiring from society,” is left without direction or purpose at 65 after having worked for 42 years.

All of them find their way to the community centre and to its wise librarian who sees in people what they cannot see for themselves. To all, she asks, “...[w]hat are you looking for?” And in each answer, she hears what is unsaid. In addition to a reading list with a surprising title at the end — books on gardening or astrology or evolution or even children’s books or poetry collections — she offers perspective and sends them off with her wisdom and a handmade “bonus gift”, as if changing lives is routine work for her. It is no surprise that the characters, by virtue of unexpected, insightful discoveries, soon start putting their lives together.

Typical of a book with multiple characters, their lives intersect in subtle ways. But what is worth noting is that instead of occurring parallelly, the characters’ lives progress in a linear fashion. Their paths cross but they do not overlap or overstep in one another’s journeys. In a fast-paced world driven by thrill, Aoyama’s book helps us slow down, reflect, and appreciate the silent ways in which life works, bringing us right where we are supposed to be despite the “endless merry-go-round” it is. At the same time, it celebrates the social and cultural values of shared spaces like community centres and libraries.

As a reader, I value Aoyama’s philosophy: whatever the question may be in life, the answer is always inside a book. While it is true that life can be restored inside the sanguine walls of a library — as the book intends — Sayuri Komachi's library has its shortfalls that must also be addressed. As one of the characters, Natsumi, learns from a book recommended by the librarian, "the heart has two eyes" — the logical, critical “Sun Eye”, and the emotional “Moon Eye”; we, too, must see the story through both of them. Men who do the bare minimum at home and labels such as NEET, a formal acronym in Japan, may seem strange to the rest of the world that is trying to move away from such old-line ways. Although probably (hopefully) not done deliberately, descriptions of the librarian’s physical appearance — comparing the “humungous, fearsome woman” to a “polar bear curled up in a cave for winter” or “Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man” — are problematic. Moreover, the characters’ familiarity, as drawing and comforting as it can be, wears off with each passing story, leaving behind a trite and overused credo.

Nonetheless, Aoyama’s book will mean different things to different readers depending on where they are in life and what they are looking for. As the wise librarian says, “Readers make their own personal connections to words, irrespective of the writer’s intentions, and each reader gains something unique.”