Ed Husain, the author of The House of Islam, earlier created ripples by writing The Islamist. The gulf between Islam and the West is widening. Islam is observed by nearly two billion people across the world. It is a faith rich in strong values and traditions but is perceived by the West as something to be feared rather than understood. Sensational headlines and hard-line policies spark enmity, while ignoring the sentiments, narratives and perceptions that preoccupy Muslims today. In this context, the present volume is a timely publication.

The author escorts us compassionately through the nuances of Islam, contending that the Muslim world need not be a stranger to the West, but a peaceable ally. The House of Islam enables us to enter the minds and hearts of Muslims the world over. It unveils the fairness, kindness and mercy of Muhammad; the aims of Sharia law, through a commentary on the scripture, to provide an ethical basis to life; the beauty of Islamic art and the permeation of the divine in public spaces. We are informed about the crisis within Islam when the author reveals the tension between mysticism and scripturalism. This prevalent tension challenges Samuel P. Huntington’s notion of the ‘clash of civilizations’ involving the West and Islam.

The author argues that at times the ignorance of the Muslims themselves about the essence of Islam can contribute to the emergence of extreme authoritarian forces within Muslim societies. For example, the Iranian leader, Khomeini, formalized the title, Ayatollah (meaning ‘sign of God’) for himself. Religious extremism has gripped Iran’s government since 1979. The West does not understand Iran’s messianic creed of Wilayat al-Faqih (Rule of the Cleric), a form of caretaker government while waiting for their promised messiah, known as the infallible Mahdi. In the name of preparing for this perfect Mahdi, the clerical government justifies its tyrannical rule. For a thousand years, Shia Muslims had no such concept of clerics governing in absence of their Mahdi. Khomeini invented this power trick and now Iran seeks to influence other Shia communities around the world with this dogma of Wilayat al-Faqih.

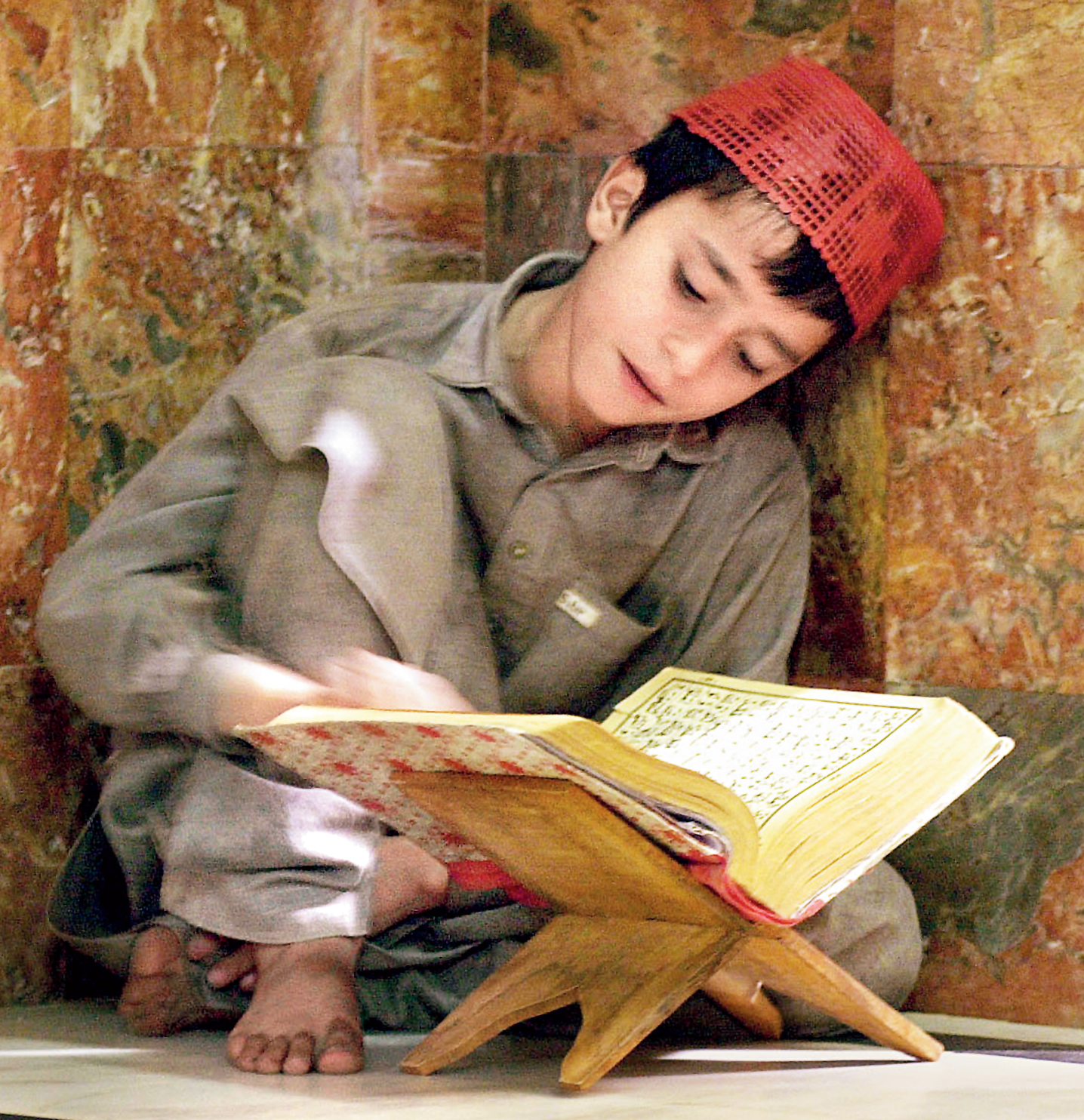

A boy in solitary study of the Koran at the Mohabat Khan Mosque in Peshawar, Pakistan near the Afghanistan border Image: Chris Hondros

Iran’s support for terrorism through Hezbollah or Hamas against Israel, or its attempt to acquire nuclear weapons, are driven by an imaginary apocalyptic war with the West and its allies. The Iranian government has gained each time the West has blundered. The terms such as Ayatollah or Wilayat al-Faqih are innovations (bida) and are not acceptable in Islam itself. But the majority of Muslims did not question their legitimacy.

The author is convincing when he says that a large section of Muslims do not try to understand the significance of certain events which took place during the Prophet’s lifetime in the context of the 20th or 21st century. For example, the Prophet created a social contract with Jews and others in Medina, known as the Constitution of Medina, to bring an end to the bloodshed between tribes, and thereby established the rule of law. This Medinan Constitution should not be exclusively viewed as a stabilizing factor. It also demonstrated how the Prophet could anticipate the significance of pluralism. This cosmopolitan spirit is being threatened by homogenizing propensities for quite some time now. The application of the one country, one religion and one language (Arabic) formula in Northern Africa and some other parts confirms this claim. Can it be said then that posterity has always tried to emulate the cosmopolitan Prophet?

The author makes an impassioned appeal to expel violent extremists from within Islam. The House of Islam is on fire — and the arsonist still lives there. It is no longer enough simply to condemn terrorism. As long as the House of Islam provides shelter for Salafi jihadis, the rest of the world will attack Islam and Muslims. Muslims need to cleanse the mosques, publishing houses, schools, websites, television channels, madrasas and ministries of Salafi-jihadi influences, otherwise Islamophobia will continue to rise, argues the author. Islamists and Salafists seek to suppress thoughts of coexistence not only with Israel but also with other Muslims, particularly Shia believers. In 2017, more than 300 Muslims, including women and children, with Sufi orientation had been massacred in Egypt. Just as Pakistan was held in deep distrust for harbouring Osama bin Laden, the role of its madrasas and for assisting North Korea with nuclear technology, today the entire Islamic world is considered suspect for harbouring terrorists. There needs to be a global declaration by all 50-plus Muslim governments and their Islamic leaders that would disown these theological brigands as disbelievers. The author justifies his suggestion by citing examples from early Islamic history when great Muslim scholars declared violent and destabilizing elements to be non-Muslims.

The book articulates such suggestions boldly. They might help us know our neighbours better. That understanding is now in crisis. It is our collective responsibility to encounter this crisis to build a better tomorrow.

The House of Islam: A global history By Ed Husain, Bloomsbury, Rs 499