Book: On the Scent: Unlocking the Mysteries of Smell – and How Its Loss Can Change Your World

Author: Paola Totaro and Robert Wainwright

Published by: Elliott & Thompson

Price: Rs 999

“... [A]t the very instant when the mouthful of tea mixed with cake crumbs touched my palate, I quivered, attentive to the extraordinary thing that was happening inside me.”

The above-quoted lines, taken from a seminal passage in literature describing the ‘Proustian moment’, enlighten readers about the magical nature of sensory stimulation. What the French novelist, Marcel Proust, did was unpack the inextricable link among memory, emotion and external stimuli like smell and taste in his literary endeavour. But to imagine a world where one of these senses is defunct or lost would, indeed, be appalling; it would significantly alter the perception of not only our surroundings but also the sense of self. Incidentally, SARS-CoV-2 did just that. It jolted us to the reality of losing one of our vital faculties, compelling the re-evaluation of our understanding of the olfactory sensation. Paola Totaro, a London-based journalist, was among the millions affected by the first onslaught of Covid-19 in March 2020, leading to her being diagnosed with loss of smell. In On the Scent, Totaro, along with her

writer husband, Robert Wainwright, uses her unnerving experience as the rohstoff to embark upon an investigation into its causes and implications, thereby shedding light on olfactory science in the process.

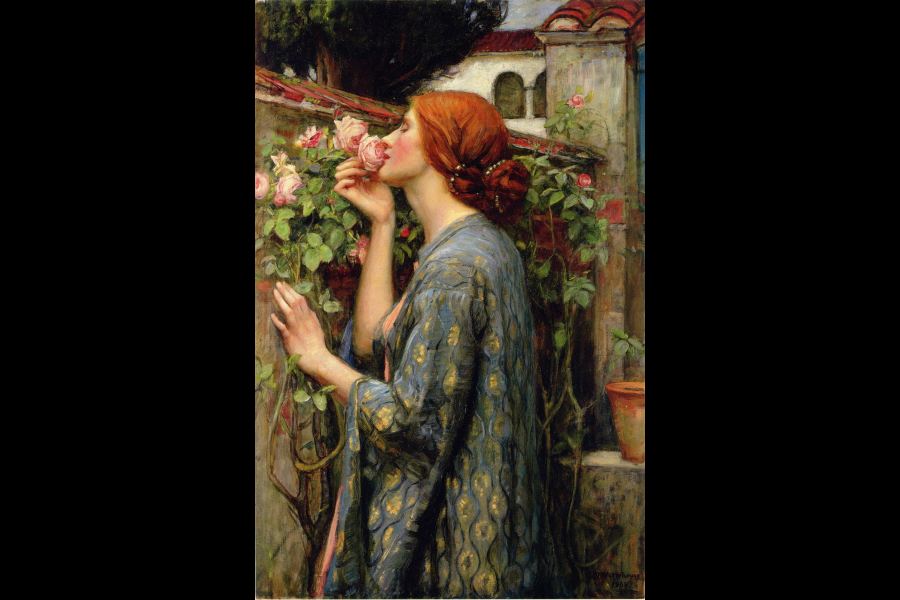

At a broader level, On the Scent is a profound appreciation of the “Cinderella” of the senses. The authors delve deep into the diverse dimensions associated with the faculty — its “poor cousin” status among the senses, its function as a health sentinel, the modalities of anosmia (total loss), hyposmia (partial loss) and phantosmia (smell hallucination), its significance in evolutionary biology and perfumery and so on. Such is its indispensability to the objective perception of reality that when Totaro lost her sense of smell (she recalls the exact date and time), it felt like a “light turning off”. Thus, red wine tasted like “salty water”, steak “slab of flabby leather” and dark chocolate “unscented soap”. Thereafter, her quest to regain her lost sensory ability, including a weighty focus on scent-training that will resonate with Covid survivors experiencing anosmic tendencies, propels the narrative forward.

Totaro approaches her syndrome with a sense of bereavement. When she finally gets her sense of scent back, it is, interestingly, through the memories of her late grandmother. The profiling of anosmics, such as William Wordsworth, introduces an interesting element. The narrative also shifts — abruptly — to the first-person narration of Wainwright in “My Designated Nose”, offering the perspective of the caregiver.

While inquiries into the olfactory vocabulary were illuminating, the authors’ reliance on scientific jargon may render the book esoteric. Nevertheless, On the Scent is a valuable addition to the knowledge about smell and the self.