The Sabarimala Confusion: Menstruation across Cultures — A Historical Perspective By Nithin Sridhar, Vitasta, Rs 895

All hell broke loose when the Supreme Court lifted the ban on women between the ages of 10 and 50 — deemed to be the menstrual years — entering the Ayyappa temple at Sabarimala in Kerala. Supporters of the ban, within the state and elsewhere, viewed this as a direct attack on a tradition that had, for centuries, safeguarded the chastity of their Lord Ayyappa. What they did not know — and which many, perhaps, chose to wilfully ignore — was that the ban was merely a few decades old, and not some ancient wish of the almighty.

It was only when the temple was rebuilt in the wake of a fire in 1950 that its popularity among devotees skyrocketed. After this, the first formal, and inexplicable, restrictions on women entering Sabarimala were said to have surfaced — a series of notifications sent out by the administrative authorities of the temple prohibited the entry of women between 10 and 55, on the grounds that it went against “the fundamental principle underlying the pratishtha”. Subsequently, women were forbidden under the Kerala Hindu Public Places of Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Rules from setting foot in any holy place “at such time during which they are not by custom or usage allowed to enter a place of public worship”. There is little doubt what this “time” is.

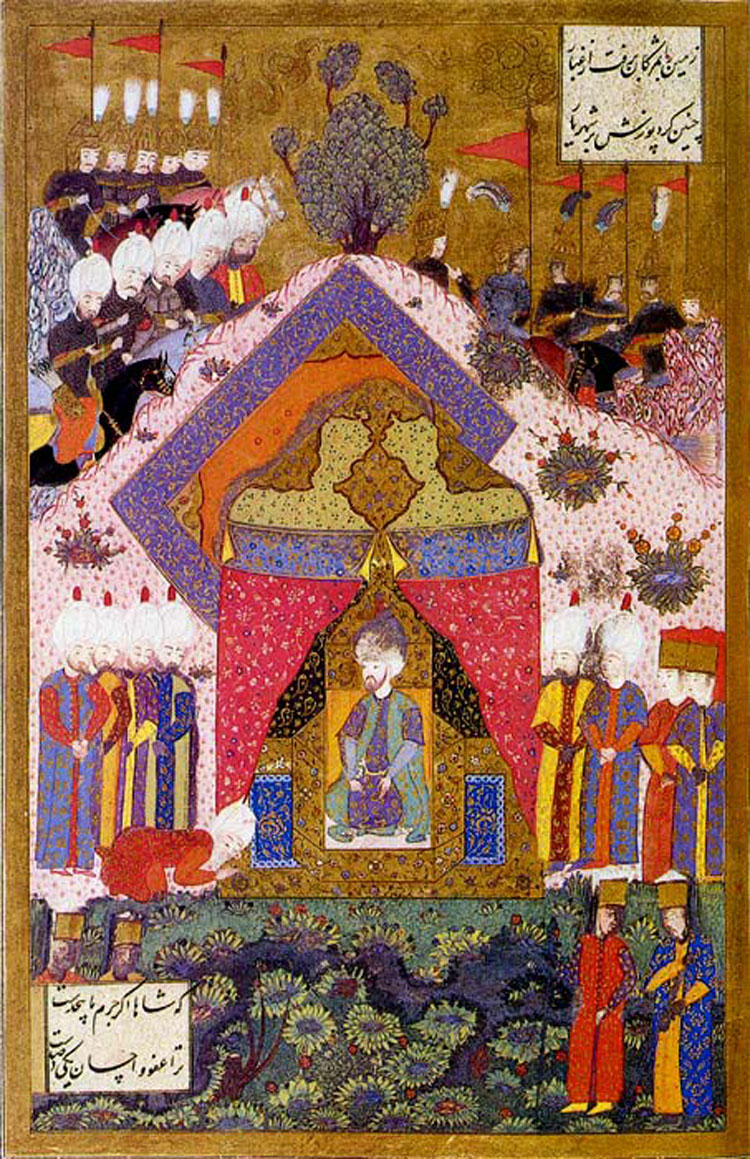

That women were allowed to worship at Sabarimala is highlighted in The Sabarimala Confusion, Nitin Sridhar’s apparent attempt at dispelling myths associated with interpretations of menstruation and worship in Hindu scriptures. It is not clear, though, what exactly the author is trying to ‘dispel’. The purported objective of the rather extensively-researched book is to discredit myths about the traditional approach to menstruation in Indic traditions, especially with regard to women’s right to worship. But it does not do that. A lot of the material, including direct quotes from holy texts and Sridhar’s own explanations, seems to reinforce rather than question regressive notions.

For example, the Angirasa Smriti asks women on their period ‘not to engage in holy/sacred activities’, while the Vashistha Dharma Sutra directs them to ‘not touch fire’ — a clear reference to not cook food — as well as to stay away from worship rituals involving fire. The author ‘explains’ these instructions thus: “For performing any ritual, an individual should be physically clean, as well as mentally pure and calm and... have Sattvik disposition.... Since menstruating women have heightened level of Rajas... they become ineligible to perform or participate in any religious activities.” It is unclear what myths are being dispelled here. If anything, these only bolster the toxic message communicated over centuries: women, especially of reproductive age, pollute the (very male) purity of places of worship. Sridhar does provide a feeble argument about the need for women to ‘rest’ during menstrual cycles being at the core of such tenets, but that message does not really seem to hold.

In a country where taboos ensure that women do not have access to menstrual hygiene and often die from infections, it is more important than ever to mould the narrative on menstruation to focus on hygiene and rights. As such, it is perhaps a good thing that the book’s dense, academic text puts it out of the reach of lay readers. The last thing that women in India need is scholarly validation of regressive societal beliefs, or attempts to use ancient shastras to ‘help’ women’s movements.