In his poem “The Sun Rising”, John Donne uses two words to identify India: spice and mine. Donne’s 16th-century contemporaries would have made the same connection. Reorienting the discourse in the new millennium, this easy connection still stands. The word used has changed; masala, or the Indian (originating from Urdu ‘masalah’ and the Arabic ‘masalih’, now used throughout the country) word for spices has been connected to no less than William Shakespeare himself in Jonathan Gil Harris’s new book. In a sense, this is a brave connection given the lengths to which the British colonial establishment in India had gone to insulate Shakespeare from ‘native’ influences. Harris, of course, recognizes in Shakespeare a plurality and the refusal of every kind of partition, two traits that are for him ‘Shakespeare’s masala’. Masala, for him, is not just spice but the mixture of spices. Harris’s book also has multiple aspects to it as the title itself makes evident. The Indian reception of Shakespeare is to be read through the lens of the masala, something that then influences even global appreciations of the bard. Simultaneously, the masala that is India is to be viewed through Shakespeare; the myriad-minded man seems to be everywhere in Indian culture. Finally, the understanding of India, even after all these centuries, is still as a masala, exotic and orientalist in its odour.

Masala Shakespeare is an erudite book, albeit one that is supposed to cater to non-academic audiences as well. Harris takes a wide range of examples, from the Indian adaptations of The Comedy of Errors, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet to the more modern globally known adaptations of Macbeth, Othello and Hamlet by Vishal Bhardwaj and of Atul Kumar’s Twelfth Night staged following the nautanki tradition. Harris also provides an exhaustive critique of Shakespeare adaptations, mainly films, in regional Indian languages such as Bengali, Marathi, Tamil and Meitei. Although he also discusses print adaptations such as Utpal Dutta’s Macbeth or Chaitali Raater Swapno (an adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar’s Bhranti Bilas (an early adaptation of The Comedy of Errors) and some theatre productions, Harris is mostly interested in discussing film adaptations. The films that he discusses are almost always loosely connected to some element of Indian culture.

Linking Twelfth Night to Vikram Seth’s novel, A Suitable Boy (where two of the characters are shown rehearsing the play), A Midsummer Night’s Dream to Saikat Majumdar’s The Firebird, and the storm in The Tempest to Amitav Ghosh’s book on climate change, The Great Derangement, Harris also sees Shakespeare as a key figure in Indian writing in English. Similarly, Shakespeare’s ‘masala’ is ubiquitous in addressing all aspects of Indian culture, according to Harris — whether it be India’s linguistic diversity, many religions or the caste-system, all of these are addressed through Shakespeare’s plays. Of course, the subtitle of the book, How a firangi writer became Indian, is one that can describe the author as well and there are many biographical anecdotes. The author makes many direct connections to his own experience of India with the assumption that the reader is able to identify with him. Sadly, that is unlikely to be the case. Not every reader, even if he or she is Indian, will recognize the Bollywood song “Jhalla Wallah” and appreciate why Harris sees it as a key element in his understanding of masala Shakespeare. Likewise, the liberal use of Hindi and Urdu words interspersed within the predominantly English text might pose problems for the non-Hindi speaking reader. Harris, of course, is trying to stay true to his idea of masala even in his writing. He, however, privileges one or two Indian languages in his attempt to show plurality and mixing.

There have been many earlier academic analyses of Shakespeare using frameworks of plurality, hybridity and transculturation; Masala Shakespeare certainly adds to the debate. Arguably, however, by trying to link every aspect of Indian culture, the book overstates the case. For example, Harris links the tale of Hiranyakashipu and Holika (the mythological story connected to the festival of Holi) to Shakespeare’s Macbeth because he sees a common trait in Macbeth’s and Hiranyakashipu’s false assumption that they are immortal — such a comparison ignores the complex differences between the two narratives that are too many to even list. Barring a very brief but incisive discussion of Merchant and Ivory’s film Shakespeare Wallah, Harris does not address the colonial approach to Shakespeare and the Indian responses, such as the influence of Shakespeare on Bankimchandra Chatterjee’s Kapalkundala or the comparisons that both Chatterjee and Rabindranath Tagore make in their essays on Shakuntala and women in Shakespeare (Miranda, in particular). Also, Shakespeare’s masala seems to be restricted to the plays alone — the poems and the sonnets are a notable omission in Harris’s otherwise exhaustive analysis of Indian adaptations of Shakespeare.

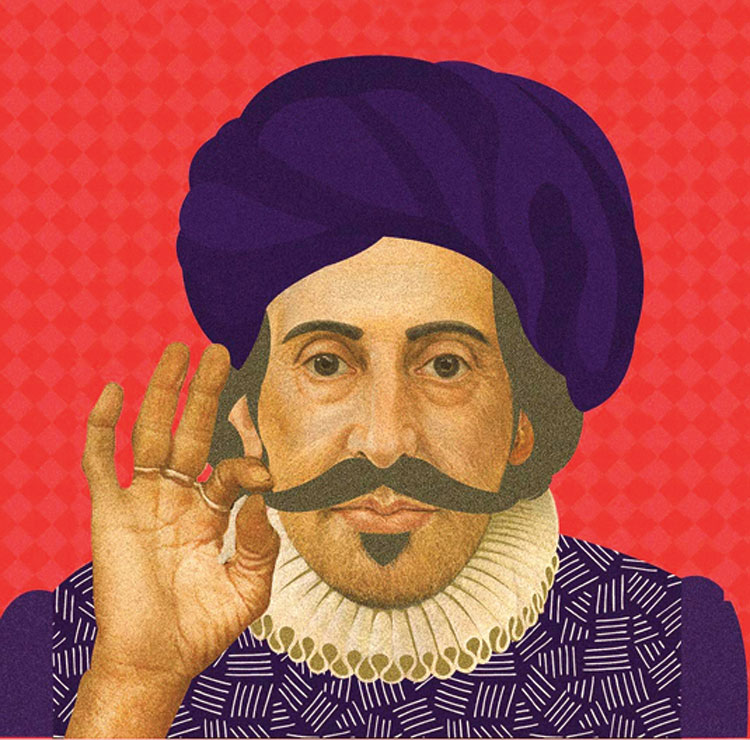

This is, nevertheless, a fresh entry point into reading Shakespeare, especially considering the rich diversity of Indian adaptations of his plays, both in Bollywood and in regional cinema. Harris’s in-depth and wide-ranging survey is both an entertaining and enlightening guide to the reception of Shakespeare in India. Partly autobiographical, with tales from the author’s childhood in New Zealand, the stories of his marginalization as a higher education student in the United Kingdom and the whole idea of a mixed and diverse upbringing are given an interesting perspective through the figure of Shakespeare and his plurality: as he says, he is “a Jewish-Kiwi-Anglo-Irish love jihadi, partnered with a Malayali from a Hindu Nair family”. Breaking free of the usual academic restrictions of Shakespeare Studies, Harris identifies masala as the framework that transcends boundaries and Shakespeare becomes the medium for thinking through diverse and multiple notions of history, politics and identity. The cover-image of the book is especially symbolic: the morphed image of the famous Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare showing the bard sporting a mustachio and wearing a turban is a fitting illustration of a project that shows Shakespeare as diverse and plural in his Indian setting.

Masala Shakespeare: How a Firangi Writer Became Indian; By Jonathan Gil Harris, Aleph, Rs 799