Feisty young writers from the West Indies with a remarkable clarity of vision have been asserting their identity in the last few decades and forging an eclectic and burgeoning readership globally. Telling their troubled stories of acculturating in America, Britain, or Canada as immigrants, they paint busy canvases with daily events that reflect homelessness, a pastiche of languages and a continuum of disparagement they face in their new adoptive homeland in the West.

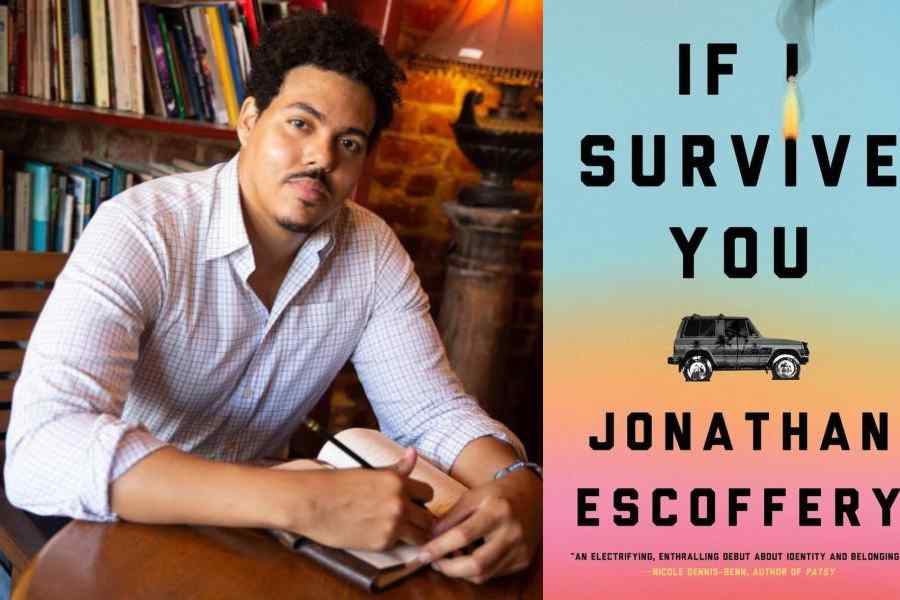

Like most writers who have inherited the legacy of colonial history, the newest kid on the block, Jonathan Escoffery, is a polyglot. He is comfortable in many tongues and speaks several languages and puts the patois, speech or language that is non-standard to effective use in the narrative.

That lends the story a certain stamp of uniqueness of place and culture. The story is as much about identity as it is about language, a primary marker of the mother tongue. Thus, the first sentence of the novel grabs the reader with the irreverence the protagonist Trelawny, a young Black immigrant in Miami, has to face as a factory fresh import from his native Kingston, Jamaica.

“It begins with What are you? hollered from the perimeter of your front yard when you are nine — younger, probably. You’ll be asked again throughout junior high and high school, then out in the world, in strip clubs, in food courts, over the phone, and at various menial jobs.”

Escoffery then writes about a question the protagonist, Trelawny, gets.

“Why’s your mother talk so funny?” your neighbor insists. Your mother calls to you from the front porch. … this signals that playtime is over, only now shame has latched itself to the ritual.”

Thus, from the very first chapter, In Flux, we are accosted by the change of reception of the Black family by the larger White American milieu. In Jamaica, Trelawny’s light-skinned, mixed-race parents feel superior to those with darker skin. Growing up in Miami, he’s mistaken as Dominican; in college in the Midwest, he becomes “unquestionably Black”. So, from the outset, the two prickly issues of colour and language take centrestage.

Where the writer hits his stride is in the way the novel unpackages the complexities in the relationship between the brothers Delano and Trelawny and the sharp discriminations the Blacks mete out to other Blacks. For instance, one of the most fascinating exchanges between the Black server /waiters and Black clients is the revelation that a Black waiter in a restaurant might treat the Black customer who comes in a group of White and Black customers with disdain: as if to say “Oh, you are one of ‘us’. You look just like us.”

So, the observation that the novelist makes through his Black protagonist is of a Black server at a restaurant handing menus to White guests before Black guests. In that way, If I Survive You is an ethnographic piece of fiction. Add to that, the protagonist finds himself homeless and looking to earn some dollars by getting odd jobs on Craig’s List — such as a White couple wanting a Black man to watch them have sex, and yet another woman wanting a Black man to give her a black eye — and Escoffery earns some extra points for unique real-life documentation of race and its humorous expressions.

Jonathan Escoffery invokes his countryman, the celebrated Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott, by training the spotlight on the complex intermingling of formal English and American English spoken by different classes of Blacks, a Jamaican patois which is a chutneyfication of different dialects and registers of the local Jamaican tongue and English. It is to Escoffery’s credit that he is comfortable in the West Indian patois as well as the other ‘Englishes’. The author establishes a refreshing presence with his own voice and own unique tongue to tell the story.

As Derek Walcott had said:

“Despite your Empire’s wrong,

I made my first communion

There with the English tongue.”

Like many other Postcolonial poets and novelists before him, Escoffery actually “performs” what Raja Rao, our own grandfather of Indian writing in English, had strongly recommended in 1936 in his foreword to Kanthapura to writers who came from colonised nations: “We cannot write like the English. We should not. We cannot write only as Indians. We have grown to look at the large world as a part of us. Our method of expression, therefore, has to be a dialect…”

Jonathan Escoffery is using his academic acumen with panache and good strategy: he is the recipient of the 2020 Plimpton Prize for Fiction, a 2020 National Endowment for the Arts and Literature Fellowship, and the 2020 ASME Award for Fiction. His fiction has appeared in The Paris Review, American Short Fiction, and Electric Literature, and has been anthologised in The Best American Magazine Writing. He received his MFA from the University of Minnesota, and he is a PhD fellow in the University of Southern California’s PhD in Creative Writing and Literature Program. In 2021, he was awarded a Wallace Stegner Fellowship in the Creating Writing Program in Stanford University.

And he has several contemporaries who are putting their creative writing training and skills to join the global reader in their living rooms, to open windows to the real challenges of acculturating in America — even when it is Blacks from the Caribbean islands acculturating with Blacks in America. In February 2022, Ayanna Lloyd Banwo, a diasporic West Indian doctoral candidate in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of East Anglia, who lives in London, quickly became the reigning flavour among the new crop. Like Banwo, this newest writer from “the islands” has some big shoes to fill.

Escoffery’s senior colleagues Trinidadian Shani Mootoo (of Out on Main Street and The Cereus Blooms at Night fame), and Jamaica Kincaid (with her iconic bildungsroman Annie John, still considered one of the most touching explorations of West Indian beliefs in the spirit world, culture and womanhood) have raised the bar for new entrants. Escoffery puts his own heart and his own words into his protagonist’s mouth, because those words that flow from personal hurt and humour must find their way into the world.

“You were born in the United States and you’ve got the paperwork to prove it. You feel pride in this fact, this inalienable status. You belt Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A” on the Fourth of July and even more emphatically after visiting your parents’ island nation for two weeks in your ninth summer. You disagree with every aspect of the island life, down to the general lack of central air-conditioning. You prefer burgers and hotdogs to jerked curried anything. Back at home your parents accuse you of speaking, and even acting like a real Yankee. But if by Yankee they mean American, you embrace it. ‘I speak English,’ you respond.”

Julie Banerjee Mehta is the author of Dance of Life, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College.