Book: We, The people of the states of Bharat: The making and remaking of india’s internal boundaries

Author: Sanjeev Chopra

Publisher: Harvard

Price: $27.95

That India’s present map does not exhibit the original British dominions and numerous princely states implies that great swathes of territory have been realigned in keeping with national and local aspirations. While much has been written on the territorial divisions of pre-colonial and colonial India, the internal rearrangement of the nation post-Independence via assimilation of disparate dominions and accession along with State formation and fragmentation is less delved into. Sanjeev Chopra’s book explores this making and remaking of India’s internal boundaries chronologically. This decades-long process is examined through intriguing maps, historical events and anecdotes that highlight past boundary changes, the give-and-take of territories, the tussles between Central authority and regional identities and the latent desire for self-determination.

The territorial gains from the astute positioning of the Dominion of India as successor to British India and its subsequent morphing into a new Republic are detailed, especially the negotiations with the Nizam of Hyderabad and Maharaja Hari Singh of Kashmir. While Hyderabad and Kashmir represented parallel cases of contested integration, the case of India’s northernmost region has continued to fester due to internal and external issues, as was brought to the fore by the recent creation of the Union territories of Ladakh and Jammu & Kashmir.

The importance of the first Hindi map of India that identified the Hindi heartland, the predominant demographic group and region in Indian politics, is noted accordingly. The backlash from southern states to the aggressive positioning of Hindi as the lingua franca created the setting for the consequent divisions along linguistic lines, with Andhra being the first to be formed out of the Telugu-speaking districts of erstwhile Madras. The creation of Telangana has provided a second state for Telugu speakers but the issues of linguistic and cultural identities continue to underpin the nation’s political rhetoric. Similarly, the workings of the States Reorganisation Commission are outlined as India continued to reorder along linguistic lines with the rise of monolingual states hastening the territorial fragmentation of large administrative units into increasingly smaller, but socio-culturally homogeneous, constituents. The ongoing demands for separate statehood are emblematic of such a desire for devolution of greater control into smaller ethnic entities. The Roy-Sinha proposal for merging West Bengal and Bihar into a supra-state to accommodate refugees from East Pakistan presents an interesting parallel to current discourses on migrants and citizenship. The issues of enclaves and the need for territorial contiguity that have defined West Bengal’s eventual form are succinctly noted. Sikkim’s integration and the Northeast’s divisions, the creation of Odisha, and the assimilation of Goa and Pondicherry eventually formed the current Indian Union.

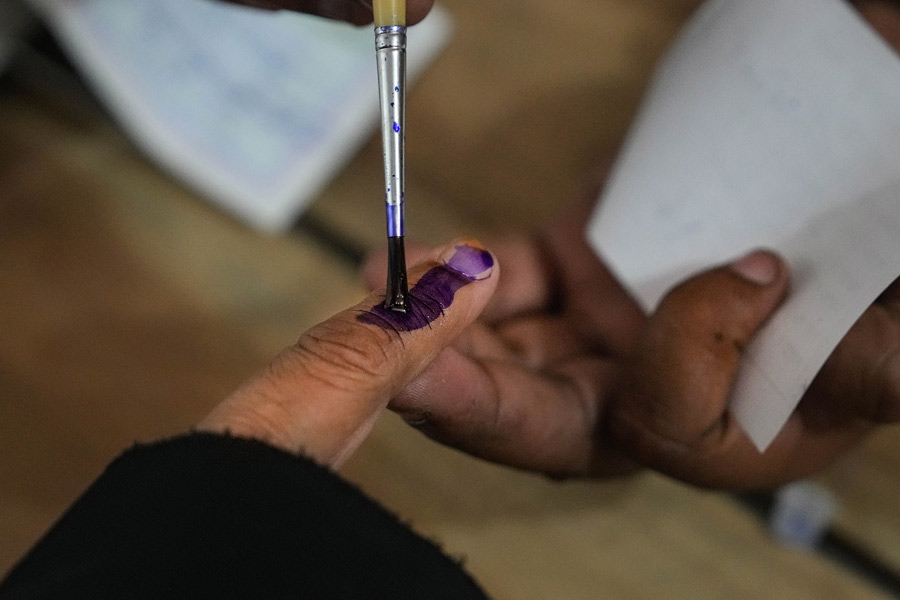

Chopra details each region’s account lucidly. He alludes to the inherent North-South dynamics in India’s electoral geography and how the country’s political cartography has altered over time, with implications for gerrymandering and targeted demographic exercises for political gain. This is thus not just a map-based look at India’s past divisions but a valuable insight into how the nation has rearranged itself and may continue to redefine its territory and democracy.