“The Quixote,” as Jorge Luis Borges read in the literary notes of a certain Pierre Menard, once and another true author of the œuvré nonpareil, “was first and foremost a pleasant book...” Quichotte is not. Pertinacious in its mockery of the “Age of Anything-Can-Happen”, Quichotte misses out on the simple and essential pleasure triggered by the good old Quixote — the pleasure of reading as true adventure while reality morphs into strangeness in a mad, unreal world.

Contained inside a brilliant red cover by Jon Gray, Quichotte narrates the story of a Mr. Ismail Smile (Quichotte), a 70-year-old retired sales executive of Indian origin, who, “on account of his love for mindless television”, suffers a “peculiar form of brain damage”, and embarks on a contrived, quixotic quest in la-di-da Trump-land. Unlike the ingenious country gentleman from La Mancha, Quichotte lacks a library, having lived his life in tawdry motel rooms across the breadth of the United States of America. Earlier, he had been an itinerant commercial traveller for his cousin’s pharmaceutical company, selling a strange drug across continents, across the eastern wastes of Iran, Tierra del Fuego, Serengeti plains, and the Kolahoi glacier in Kashmir. For reasons unexplained, he lacks a residential address, develops a sudden fear of flying, and commences on a road trip across America in a Chevy Cruze car to declare his love to an Indian talk-show host.

At one level, Quichotte’s quest narrative alternates with another narrative following the life of his “beloved”, Miss Salma R — a strange mix of Madhubala, Priyanka Chopra, and a Salma Hayek from Breach Candy appearing on American reality television, conceived as if in a happy narcotic haze. Like Quichotte, she lacks a proper personality: she exists to fulfil an authorial desire to run sardonic commentaries on the reality insulation of television viewers, older binge-watchers, as well as the newer “generation of Netflix-and-chill”. Childhood trauma drives Salma to addiction, one that necessitates an encounter with Quichotte.

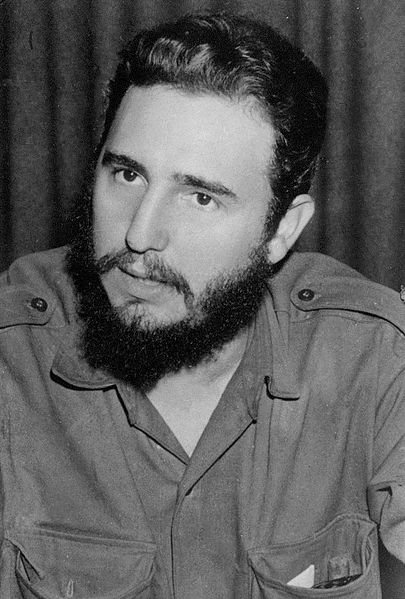

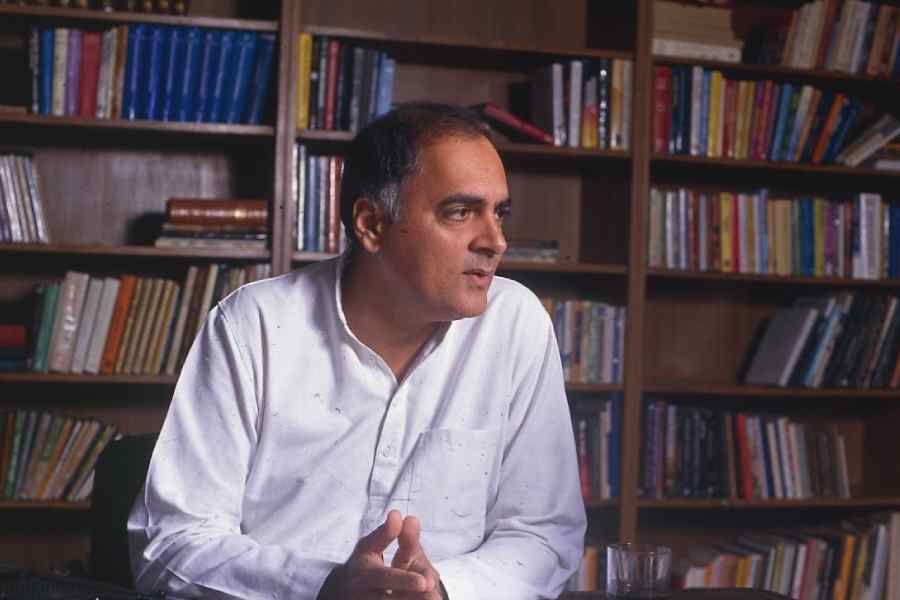

At another level, there is the story of the author of Quichotte — a deranged writer of unsuccessful spy-fiction going under the pen name of Sam DuChamp — Salman Rushdie insists that we call him Brother. Unlike the historian Cide Hamete Benengeli (who, as Miguel de Cervantes reminds us, was the old cheerful soul who really wrote the Quixote in Arabic), Brother is despicably in love with his paranoia and self-pity, and sees the world as receding into entropy. Quichotte, Salma, and Brother make long, individual mental journeys into a shared lost world of Bombay, reminiscing about Binaca Geetmala, the “unmistakable yodellings” of Lata and Asha, long-balconied apartments, abusive grandfathers, sharp cactus plants.

At yet another level, still, there is the omniscient author who half-heartedly narrates the misadventures of Quichotte and Brother. It is here that Sir Rushdie takes over the narrative: intrusive to the point of grumpiness, he offers sombre warnings to Before Google people that something has gone seriously wrong in the space-time continuum after the advent of the internet, predicating entropy and the heat death of the universe. High on sarcasm, he tries Gandalf-ing in a motley cast of characters: white supremacists in invisible dog collars, a Kansas shooter, a philosophizing cricket, the labrador Schrödinger, a Japanese-American secret service agent called Kagemusha, a hacker legion led by a Marcel DuChamp. They appear and disappear, an assortment of personality types less lively than the staggering zombies in a Jim Jarmusch movie. To make matters worse, six chapters on, the monochromatic Sancho — a 15-year-old youngster from black-and-white television — materializes out of a wish Quichotte makes to a meteor shower. As the narratives meander into the realms of the fractured and the prismatic, Quichotte, unpardonably, denies Sancho his quirks or a mind of his own.

The premise with which the fictional unreal commenced, too, begins to falter from an early point on: Quichotte’s idea of the classics (true to his being) is the 1965 Dating Game show on ABC-TV; but soon enough, he commences on making snide literary throwbacks to Cervantes, Dostoevsky, Bradbury, Alan Moore and Aristophanes. The favourite piece of music this homeless salesman falls back to in times of introspection is not a television jingle, but a “vinyl LP” recording of Jules Massenet’s opera, Don Quichotte. Who, really, is listening?

After the climactic end of Quichotte, which invokes Arthur C. Clarke’s apocalyptic The Nine Billion Names of God with super-computing dismantling the cosmic fabric of the universe, and Quichotte and Salma escaping to an alternate dimension, Brother sees his reflection speaking to him from an aeroplane window: “The world no longer has any purpose except that you finish your book. When you have done that, the stars will begin to go out.”

One can hazard a guess that Quichotte left its true author in this unfinished, overweening state. “Fame is a form,” wrote Pierre Menard before abandoning his impossible project of re-creating Don Quixote in 1939, “perhaps the worst form — of incomprehension.”

Quichotte by Salman Rushdie, Hamish Hamilton, Rs 699