Book: The Island

Author: Karen Jennings

Publisher: Pan Macmillan

Price: Rs 450

A man’s body floats up on the beach of an island; the old lighthouse-keeper is about to bury the body when he realizes that the man is still breathing. Despite the man’s weight and the onerous task of lifting him from the beach into the lighthouse, the lighthouse-keeper, Samuel, manages to take him indoors and revive him.

Karen Jenning’s highly acclaimed novel, The Island, begins with the story of Samuel, the protagonist, rescuing the refugee, who is simply called the Man, and takes the readers on a journey into Samuel’s mind, raking up issues such as colonialism, politics, solitude, humanity and care. The Man does not speak the language of the mainland so Samuel suspects that he is a refugee. Instead of informing the authorities, he chooses to hide the Man in his house. After a time, however, the Man’s presence becomes oppressive; even his smile seems to be menacing to Samuel. With every little incident, Samuel remembers his past during the political turmoil of the colonial government and, then, the dictatorship that followed after Independence. He remembers the people he had betrayed when he was in prison and how he had killed a soldier while protesting against the dictator. Throughout the novel, the reader only gets to hear Samuel’s thoughts. Jennings says in an interview that she did experiment with an omniscient narrator but that did not work out; as such, the reader is left stranded on an island listening to the old lighthouse-keeper’s disturbing thoughts while facing the incomprehensible speech of the unknown refugee, a speech that virtually translates into silence.

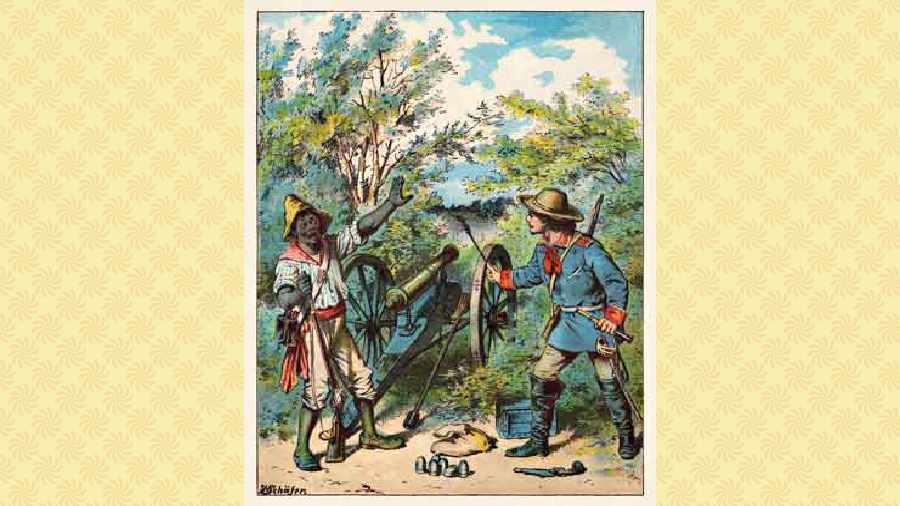

Jennings’s protagonist sits in an uneasy position: although a victim of colonialism, he resembles a Robinson-Crusoe-like figure colonizing his little island. His companion is a refugee, who is effectively silent like Crusoe’s Friday; the similarity ends there as the refugee is seen as a threat just as his actions seem incomprehensible to Samuel. The voice of the refugee cannot be heard; it is rendered silent by Samuel’s speech and placed within a framework of subalternity.

Samuel’s rescue of the dying man seems like a reparation of sorts for his betrayal of his family and friends but, at the same time, his constant suspicion of the man creates an ambiguity that is unsettling. How do victims of oppression receive and welcome others who seek refuge? Addressing issues such as political oppression and the need for asylum, the novel asks some complex questions. As a South African, white author writing from the perspective of black characters and attempting to represent a postcolonial Africa, Jennings states: “The one thing I have tried to do in my writing is to be very sensitive to who it is that I give voice to.” Nevertheless, at least for this reviewer, questions of representation arise if this novel is to be read as a representation of Africa. While the novel serves as an allegory of the complexities of colonialism, the sense of belonging, granting and seeking hospitality and refuge, it chooses to play out one scenario out of the many. Indeed, instead of representing Africa and its peoples, it could well depict the refugee crises in mainland Europe.

The island has always been a powerful metaphor for society. Jennings’s protagonist, in self-exile on an island, is himself island-like in his reclusiveness, but his memories of the mainland keep connecting him with his earlier life. Extending the metaphor, one wonders whether Samuel would have remained an island wherever he went and whether he had been an island all along. His desire for solitude is in conflict with that for companionship. Ultimately, just as they seem to have reached some common ground where they watch a documentary together on Samuel’s old VCR, Samuel hears the hens fighting outside in the chicken coop and loses his temper with the Man. The Man does not belong and Samuel brings him down with the blow of a heavy stone on his head. Soon the Man’s corpse joins those that have floated in from the sea and buried by the old lighthouse-keeper.

Jennings paints a disturbing picture of humanity by unpacking the complexities of what is taken for granted. The borders between care and violence, refuge and oppression, and solitude and companionship are turned fuzzy. The lonely reader, often discomfited by the monologue of Samuel’s thoughts, wishes that the Man had a voice that could be heard in the novel but, time and again, is reminded that this is how colonialism and oppression have functioned. Unlikeable as he is, Samuel seems close to the reader — at times, uncomfortably so. After a long struggle to establish herself as an author, Jennings has finally made it to the Booker Longlist for 2021 through a novel that asks fundamental questions about humanity and unsettles the categories of oppressor and oppressed, making readers rethink such issues as subalternity, coloniality, hospitality and the ethics of care.