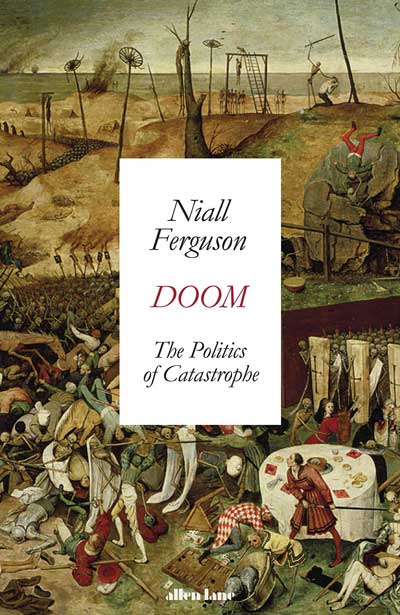

Book: Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe

Author: Niall Ferguson

Publisher: Allen Lane

Price: £25

I was expecting a tome on the politics of disasters of all manner, which Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe is, but it is clearly prompted by the infectious disease currently plaguing humanity. The word, plague, appears 188 times, as opposed to, say, flood, which appears only six times. Although Niall Ferguson covers the entire range of disasters across centuries, the ongoing pandemic has played heavily on the author’s mind.

Fairly early, Ferguson poses the central questions: why do some societies and states respond to catastrophe so much better than others? Why do some fall apart, most hold together, and a few emerge stronger? Why does politics sometimes cause catastrophe? After 395 pages of running text, the answers are far from obvious.

Doom is crammed with facts and statistics of disasters, the responses of societies and governments, and quotes fascinating studies. There is, for example, the one on the relationship between youth population growth rate and political upheaval. All countries where youth population growth rates exceeded 45 per cent over five years experienced political shocks. A youth bulge by itself is not a predictor of upheaval, but in combination with low economic growth, an autocratic State, and an expansion of higher education, it becomes so. Yet, the book is not unputdownable. Some sections, such as the one on Bugs and Networks running for over five pages, are quite a digression from the politics of catastrophe and deluge the reader with details that he/she can have elsewhere.

It is fascinating to note how extreme behaviour has, time and again, been precipitated by pandemics. In 1349, “Jewish communities... were accused of willfully spreading the plague or of inviting divine retribution by their repudiation of Christ.” Jews were brutally massacred in numerous towns; Frankfurt, Mainz, and Cologne in particular. In March last year, a prominent Muslim missionary group in Delhi was accused of wilfully spreading the SARS-CoV-2. Fortunately, the ire directed at the devotees did not result in a massacre.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson, Allen Lane, £25 Amazon

Besides the Introduction and Conclusion, the volume is divided into 11 chapters. Chapter 8, “The Fractal Geometry of Disaster”, is the most readable, the narrative riveting and the details do not come across as overkill. The initial chapters are quite a task for the reader, especially for those whose first language is not English. Ferguson does not seem to be addressing all those who can use the English language for communication but only those for whom English is part of the culture. Here, I use culture in the anthropological sense, encompassing all aspects of life, determined by membership in a society. Also at a disadvantage are those who are unaware of Greek tragedies. Readability improves as the volume progresses.

The Conclusion, titled “Future Shocks”, is revealing and thought-provoking — “Only a handful of those nations that fought World War II had lost more people per day to COVID than they had lost to the Axis powers.” The point being made is that all disasters are man-made, political disasters at some level and India is no exception but, unfortunately, Ferguson does not dwell on India much. The few references are historical, until the colonial period, except the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

All the evidence that Ferguson has marshalled makes it convincing that disasters become truly epoch-making events only if their economic, social, and political ramifications amount to more than the excess mortality they cause. The current Covid pandemic could be one such, not for the entire world, but for several countries, including India, when the prematurely dead, the lucky survivors, and the permanently wounded or traumatized are accounted for in time.

Two things that Doom drives home for me are: the shortness of human memory and that nightmare visions seldom persuade policymakers to act pre-emptively.