Celebrated Japanese-Canadian writer Joy Kogawa is a survivor of the internment camps that Japanese-Canadians who were perceived as “enemies” of the Canadian state during the World War II, were thrown into. She wrote the novel Obasan, to international critical acclaim, based on the Japanese community’s terrifying experiences, including her own, as citizens of Canada. This year is the 80th anniversary of this act of abject terror that the Canadian state had perpetrated against its own citizens on purely racist perceptions. It is also the 41st year of celebrations of the publication of this historic novel.

“Be willing to be torn apart.

God is where the struggle is.

Love is where the struggle is …”

— Joy Kogawa, recited to this author, at University College, University of Toronto

In Obasan (which translates to aunt in Japanese), prolific poet and novelist Joy Kogawa recalls her own story as a child who had weathered the Japanese internment during the World War II, when the Canadian government dispossessed the 22,000 Japanese of their homes and belongings, and threw them into internment camps, treating them as ‘the enemy’, although they were Canadian citizens. Interred under subhuman conditions with abject sanitation, hardly any heating in freezing temperatures and abysmal hygiene, many Japanese-Canadian were sick with tuberculosis and other diseases throughout their years in the camps. Some succumbed to the mental terror and never returned to normalcy. Those who survived after the war were scarred forever and would not or could not speak of their experiences to their children or grandchildren.

Swift on the heels of America’s entry into World War II on December 8, 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbour on the previous day, Japanese-Canadians, citizens of Canada, were removed from the West coast. The justification was “military necessity” for the corralling of over 22,000 Canadian citizens who looked “different”. After the war they were dislocated and never even partly recompensated for the atrocities committed on them by the Canadian government. Mothers were separated from their children, husbands from wives, brothers from sisters. The pain, sorrow and shame that pock-marked their lives for three years during resulted in many camp survivors (mainly men) committing suicide after their release because they found the shame associated with marginalisation impossible to bear.

In 1981,with the publication of Kogawa’s Obasan, something that had been kept secret burst upon the Canadian public about the racism which existed in the splintered bodyscape of what was known as pristine Canada. The telling of the distressing story of the narrator and main character in Obasan, Naomi Nakane, and the persecution of her family by the Canadian government, resulted in “the conscience of a whole nation being shaken up”.

This year marks 80 years since the internment of Japanese Canadians across British Columbia (BC). The $100-million initiative announced by the Canadian government a few weeks ago, is the result of engagement with the community, through the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC). “Eighty years have passed since the internment of thousands of Japanese-Canadians. Families were uprooted and incarcerated, forced to leave behind the lives they had worked so hard to build. It was a cruel, racist act, and the injustice still resonates today,” said Premier Horgan. “We are committing this new funding to honour the legacies of Japanese-Canadians, to continue the healing of intergenerational trauma, and to serve as an important reminder of this dark chapter in B.C.’s history.”

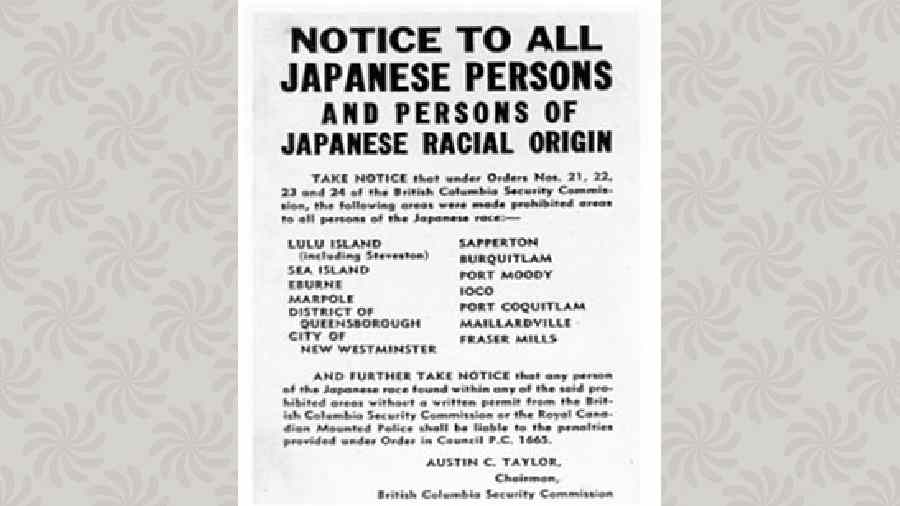

A notice issued by British Columbia banning Japanese people from certain areas in the province

In an interview with Joy Kogawa at University College, University of Toronto, some years ago, when I asked Kogawa if Obasan was a cathartic work, she said: “The action of the pen precedes the understanding that follows it. If catharsis happens, it is by chance. The work is important. This story should be known. Although it is very painful, if we deny the truth, we cannot be free. For the Japanese-Canadian redress to be felt and effective, the story of the community has to be told. In my life I have been a truthseeker to others’ detriment.”

“In the ’60s when I was writing poetry, I had written a short story, Obasan. After the war, I lived in Coaldale (like Stephen, in Obasan). Then, in the late 1970s, I had a very strange dream. In the dream I was told to go to Ottawa, and work in the archives. At the time I was coming to terms with what happened to my Mother. I find it very hard to speak of my mother,” she confessed.

Was Obasan autobiographical? “Of course”, Kogawa replied: “Obasan relates to the way my family was traumatized and how my mother’s and father’s realities broke down… It is certainly related to the history of racism, but it goes beyond that. My mother used to be such an elegant woman… Debbie [Gorham] told me that I had made these two female characters, Naomi’s idealized mother of childhood plus Obasan, because I wasn’t able to cope with the reality of what happened to my real mother. It is difficult for me to talk about her.”

Naomi, who is “motherless” since her mother is trapped in Japan just before World War II breaks out, and is not able to return home, is brought up by her older aunt Obasan, in Canada. Her mother who was in Japan at the wrong time, is a victim of the Hiroshima/ Nagasaki bombing. What makes Naomi’s estrangement unbearable is that Naomi has lost her roots in the loss of her mother and her mother tongue. Naomi is schooled in Canada and not fluent in Japanese.

In Obasan, Naomi’s grandmother Kato’s surprise, shock and a kind of perilous relief in finding her daughter, Naomi’s mother, in Nagasaki, physically mutilated by the bomb, is perhaps one of the most haunting descriptions in Obasan. At first unrecognisable, the disfiguration makes it impossible for Grandma Kato to find her daughter. It is her daughter who finds her mother:

“One evening, when she [Grandmother Kato] had given up her search for the day, she sat down beside a naked woman she has seen earlier who was aimlessly chipping wood to make a pyre on which to cremate a dead baby. The woman was utterly disfigured. Her nose and one cheek were almost gone. Great wounds and pustules covered her entire face and body. She was completely bald. She sat in a cloud of flies and maggots wriggled among her wounds. As my grandmother watched her, the woman gave her a vacant gaze, then let out a cry. It was my mother.” The silent mother is a disturbing corporeality that registers its presence as a subversive absence in Obasan. In this exploration, the body becomes the landscape of the sacred and the profane, the arena on which history is unravelled, memory is hidden and unspeakable atrocities are located.

There was an illuminating moment for me when I taught senior-year undergraduates at the University of Toronto in 2006. Two exchange students from Japan’s Waseda University expressed surprise to learn of the Japanese internment through our reading of the novel Obasan — they mentioned that this was the first time that they had heard about this event: this part of history that affected Japanese people overseas was never taught in Japanese schools or universities. There was a huge national shame that would be associated with it.

Joy Kogawa’s widely read work, an essential piece of writing that is part of World Literature and the Canadian literary canon, Obasan is a story that many Indian readers will easily chime with. India’s internment of the Indian Hakka Chinese community at camps in Deolali during our war with China in 1962 is still fresh in the minds of many Chinese who emigrated to Canada and Australia when they were made to feel like enemies to the Indian state.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches at Loreto College