The turtle lives ’twixt plated decks/ Which practically conceal its sex,” says Ogden Nash. “I think it clever of the turtle/ In such a fix to be so fertile.” This comic pithiness is also revealing: the rhyme of the last word points to Nash’s American origin. He was born this month 117 years ago in New York, carrying the legacy of a Revolutionary War general forefather after whom Nashville, Tennessee was named. But this weight did not dim Ogden’s whimsy. ‘Fertil’, pronounced ‘fertle’, is enough to produce hilarity, but coinage-wise, or distortion-wise, Nash often goes much further: “Parsley/ Is gharsley.”

Although Nash was known as the most popular writer of humorous verse in America, he bore for a long time the burden of all brilliantly funny writers. That of not being taken seriously as an artist, as an innovator of unexpected rhyme schemes and a discoverer of the insane possibilities of known words. That lacuna in critical appreciation has been redeemed; that it existed points to the belief that ‘high’ art alone is poetry. This often blinds us to the acutely functioning imagination that pushes the bounds of language and vision in comic poetry — a quality lauded as the mark of the artist in poetry that refuses to laugh.

Another burden the humorous poet carries is the label of children’s poet. True, non-human creatures frequently invite his askew gaze, but the turtle poem, for instance, is hardly for children. Closer perhaps, but far from educational, would be: “Farewell, farewell, you old rhinoceros,/ I’ll stare at something less prepoceros.” The hippopotamus invites philosophy: “Behold the hippopotamus!/ We laugh at how he looks to us,/ And yet in moments dank and grim,/ I wonder how we look to him./ Peace, peace, thou hippopotamus!/ We really look all right to us,/ As you no doubt delight the eye/ Of other hippopotami.”

Dank and grim moments were communicated in Nash’s poetry through seeming frivolity and casual satire. “In chaos sublunary,/ What remains constant but buffoonery?” he asks. The “minor idiocies of humanity” sharpened his wit: “Most bankers dwell in marble halls,/ Which they get to dwell in because they encourage deposits and discourage withdralls.” And lawyers? “Hard times for them contain no terrors;/ Their income springs from human errors.”

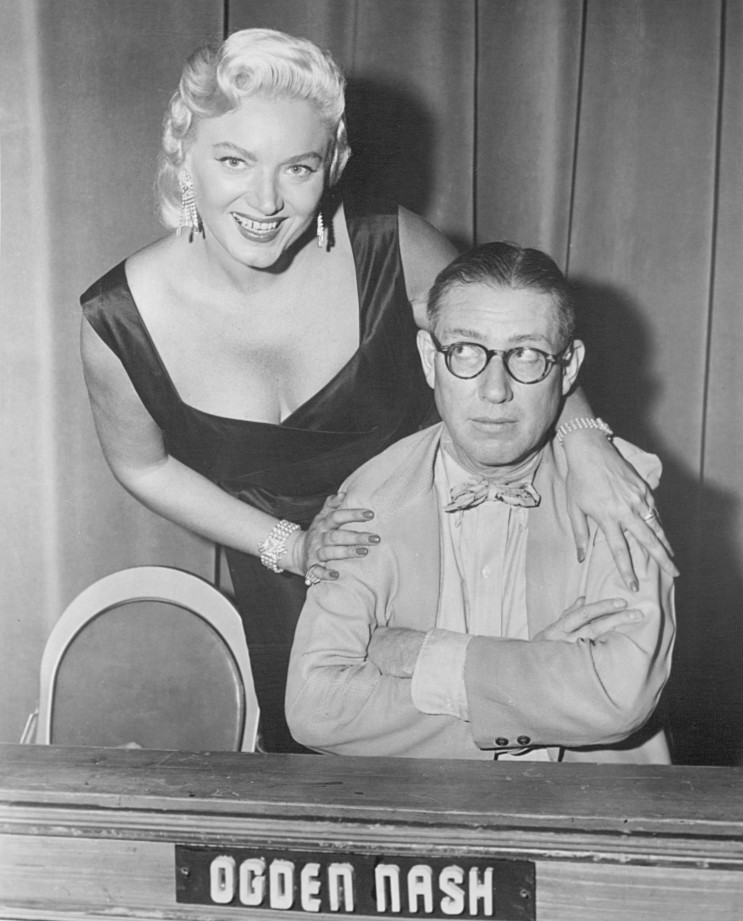

It seems only natural that the man who wrote, “If called by a panther,/ Don’t anther”, and stated that if candy is dandy, liquor is quicker, would be remembered far more for his gift of laughter than his success as a screenwriter and lyricist of a hit musical, or for his shows on radio and television. His immortality lies elsewhere: “Tell me, O Octopus, I begs,/ Is those things arms, or is they legs?/ I marvel at thee, Octopus,/ If I were thou, I’d call me Us.”