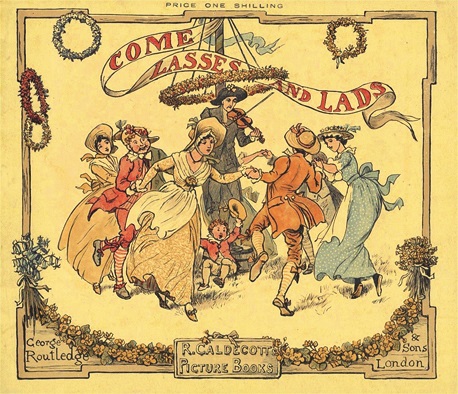

The month of May is inseparable from dancing and singing to celebrate the onset of spring. The ancient Roman celebration of Floralia as well as the Celtic festival of Beltane, which used to be held on the first day of May, including Maypole dances and the cutting of green boughs and flowers. In fact, dancing around the Maypole is one of the most enduring and epicurean rituals associated with the one day of the year when labourers across the world are granted some rest — the Labour Day tradition goes at least as far back as the Middle Ages. The scope for bawdy revelry that the phallic symbol of the Maypole provided must have been considerable.

Given the mingling between the sexes at Maypole dance, fertility symbols are ripe in literature surrounding the Maypole. In 1346, Chaucer wrote in his poem, “The Court of Love”, “Now win who may, ye lusty folk of youth,/ This garland fresh, of flowers red and white, purple and blue, and colours full uncouth...” Jonathan Swift, on the other hand, describes a Maypole thus: “Deprived of root, and branch, and rind/ Yet flowers I bear of every kind...”

The Victorians — unsurprisingly — tried to sanitize such explicit imagery, turning the ritual into the dance of rustic children. In Jack and Jill: A Village Story, Louisa May Alcott describes “a really pretty scene of children dancing round a May-pole”. Although the Maypole was stripped of its fecund possibilities, the dance itself remained full of sensual potential — even Alcott’s heroines “dance to [their] heart’s content” at extravagant parties teeming with eligible gentlemen. The novels of her successor, Jane Austen, too, are full of dances where men and women use the ruse of elaborate society dances to approach, retreat, tease and repel each other. In fact, in most of 19th-century fiction, the ball is the ultimate occasion for the kind of heady courtship that was frowned upon in everyday life.

But as we enter modernity, both dance and literary traditions begin to undergo an upheaval. Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes — a company that reinvigorated the art of performing dance — attracted writers like Mallarmé, Yeats and Virginia Woolf. “Have you seen those wonderful Russian dancers?” enquires Mrs Elliot in Woolf’s novel, The Voyage Out. From a means of excitement, dance was transformed into a mode of introspection and discovery.

The modernists thus saw in this transcendence a reflection of James Joyce’s “epiphanies”, and Woolf’s “moments of being”. In fact, in her works, Woolf questions the literary convention that used dance to identify moments of social integration. Instead, dance becomes a tool to illustrate a moment of self-discovery in her characters. In “A Dance at Queen’s Gate”, she writes, “Dance... stirs some barbaric instinct... you forget centuries of civilization in a second, & yield to that strange passion which sends you madly whirling round the room.”

The ambit of dance has expanded since. In Swing Time, Zadie Smith shows how dance can not just be a moment of personal revelation, but also be the means to transcend social barriers, like that of race, as well be a wordless, passionate exchange between two people. Dance, to her, is a demonstration of will — over both body and mind.