Thanks to my name, the Punjabis think I am a Tamil. But thanks to the way I talk and behave, the Tamils think I am a Punjabi. Or, as they pronounce it down south, Bunchaapee.

But how do I see myself? Having lived in Delhi since 1958 I have always been confused: am I a Tamil or a Punj?

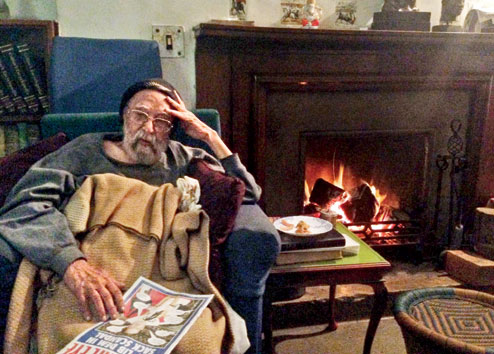

I decided to read this book in the hope that the venerable Khushwant Singh, at least, might be able to clarify my doubts. Time will tell.

In the meantime, there’s this book, telling us what exactly Punjab is and what it means to bet a Punjabi. You take the two together, and what you get is Punjabiyat.

It is, as the title of this collection of essays says, about the land which is fertile and the people who are virile. Add them and you get Punjabiyat which is febrile.

Hard work, high productivity, an aggressive preference for having a good time, a disturbing preference for aggression and a strange use of invective as punctuation in speech – these are some of the things the non-Punjabis attribute to the Punjabis.

Mr Singh says well, yes, there’s all that, of course, but above all we are a decent bunch of people who want to do the right thing and side with the righteous, if not always then often enough.

The people who live in the region, he says, are genetically a mixture of indigenous and invading tribes. Their attitudes have been forged out of being the permanent frontier. And out of all this, has grown ‘Punjabi nationalism’.

Sub-nationalism might have been a better word, but never mind, we know what Mr Singh means. More than anything else, it means a love for the land. “It is significant that the spirit of Punjabi nationalism first manifested itself in Majha, the heart of Punjab and amongst a people who were deeply rooted in the soil…its backbone was the Jat peasantry of the central plains”.

Nostalgia and history

Before partition in 1947, there were people of three major religions living cheek-by-jowl in Punjab: Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. Now the Muslims have all gone to Pakistan, leaving the Hindus and the Sikhs behind.

For many Punjabis born well before 1947, this has caused an identity confusion which is as severe as mine. Mr Singh is one of these persons. This becomes quite apparent as you read the essays. There is an implicit but subterranean harking back to a golden age of Punjabiyat. It is like married couples getting nostalgic, at least about early romance, if not sex.

Sometimes this results in Mr Singh breaking into irritating hyperbole. Here are some examples:

“Punjab and Haryana are the cradles of Indian civilisation.”

“Both Punjab and Haryana have more history than historical monuments.”

“Haryana could rightly claim to be the birthplace of the most sacred religious scripture of Hinduism.”

Well. Okay. Right you are, Sir. But now let’s move on to more accurate descriptions in which the book abounds.

These occur mostly when Mr Singh is discussing the growth of Sikhism, the development of Punjabi as a language and its literature and the post-1947 politics of the region. These essays, written in a precise and non-judgemental style, form the core of this book.

There are also a small number of mini-portraits of major Punjabis like Ranjit Singh, Baba Kharak Singh, Air Marshal P C Lal, Manzur Quadir, etc. The two surprises in this selection are Zail Singh and Nanak Singh (of Nanak Dairy).

Mr Singh doesn’t portray Zail Singh in a favourable light. He just describes him as he was – a cunning politician whose loyalty was to himself. The incidents he describes are instructive.

And of Nanak Singh, he has this to say: “Nanak Singh was of a mechanical bent of mind… he designed a conveyor belt which on the press of a button brought your chosen brand of whiskey from the shelf to the dining table.”

This too is the spirit of Punjab.

Punjab, Punjabis and Punjabiyat: Reflections on a Land and its People, by Khushwant Singh, Edited by Mala Dayal, Aleph, Rs 599

‘The Spirit of Punjab’

This is the title of one of the essays. It captures the defiance that many see as the hallmark of Punjabis and Punjabiyat. It also provides many facts that are not fully appreciated by the others.

Mr Singh says 50 lakh Sikhs had to get out of West Punjab when it became Pakistan. He says they left behind 21,448 square kilometres of land. The Muslims from East Punjab who had to go off to Pakistan left behind much less – 15,580 square kilometres. The properties left behind in Pakistan were worth Rs 500 crore. The properties left behind in India were less than Rs 100 crore.

“To this day Pakistan has not paid a single anna to compensate for the difference,” writes Mr Singh. He tells us how these refugees rehabilitated themselves without ever whining or begging for favours.

That, in essence, is the spirit of Punjab, the true Punjabiyat.