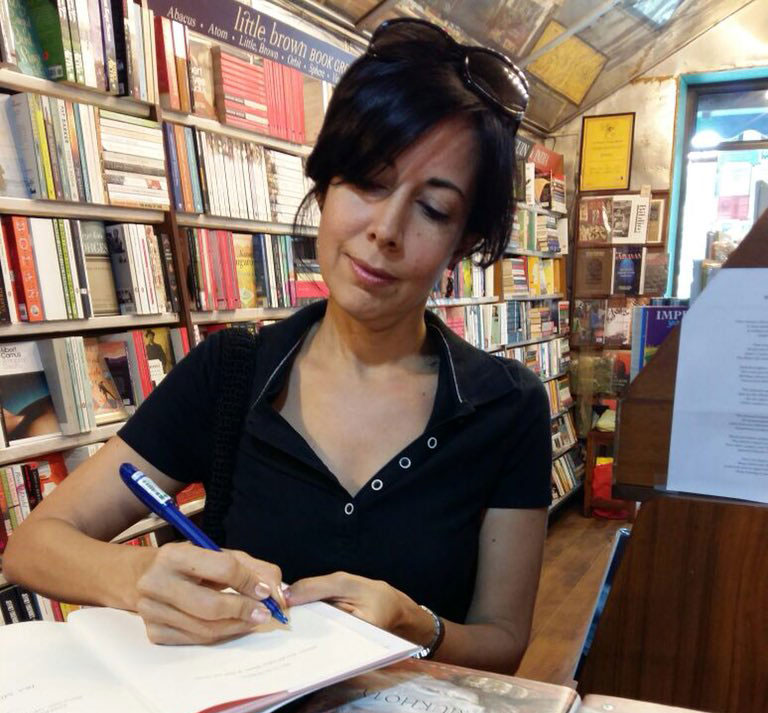

Sit with author Ira Mukhoty for a few minutes, and you’re sure to get transported to another century, a different era. t2oS caught up with Ira for an exclusive chat during the Jaipur Literature Festival.

What is your book Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire essentially about?

It highlights that through 200 years, what these harems or zenanas became was a very different institution than what we believe. What we are taught is a very colonial interpretation; the British wrote with a certain view. Whenever they heard the word polygamy or purdah or veil, they thought that those women are degraded, that they have no rights, freedom, inputs, education or money.

I wanted to show that when the early Mughal women came, for example Babur’s aunts and sisters and mothers, they were with him on horseback and they travelled all over the countryside; there wasn’t a certain closed space. They were riding next to the king, giving him their advice because he was young. His mother and his grandmother were key to Babur and similarly all the Padshahs were extremely close to the Timurid women, the matriarchs. And slowly, with Akbar it became more settled and then the Rajput local indigenous women integrated in this Mughal harem and they brought in their influence. So the clothes became tighter, like the cholis and the ghagras, the food changed…. Maybe the other Hindu Brahmins around him also influenced him but don’t you think he would be very influenced by his wife, a Rajput?

I wanted to bring out the women’s influence and not just the men’s side of Mughal history.

How difficult was it to write the book in today’s India?

When I started writing this about three years ago, I suppose it was naive of me. I didn’t realise the extent of the political sentiment. I think you will see that through their 200 years of living here, today everything that we have around us, whether it’s the food we eat, especially in North India, the clothes and perfumes we use, the language we use, even our nostalgia like Mughal-e-Azam… what is that? That is Mughal!

What sort of research went into writing such nuances?

It’s important to look beyond the sources that have been used so far. Abu’l-Fazl’s biography talks about Akbar in a certain way because he wanted to bring him out as a divine king whose manner was very orderly; this is what he wanted to show. There’s this biography of Gulbadan Begum, Babur’s youngest daughter. In Akbar’s reign, Akbar asked her to write a biography about his father and grandfather — Humayun and Babur. It’s a unique documentation by a woman in the 16th century and yet it was forgotten and lost. And then in the late 19th century, an English collector happened to find it in a bazaar somewhere, bought it, had it translated in England and realised it is Gulbadan Begum’s first-hand account from the zenana. It’s extraordinary, right?

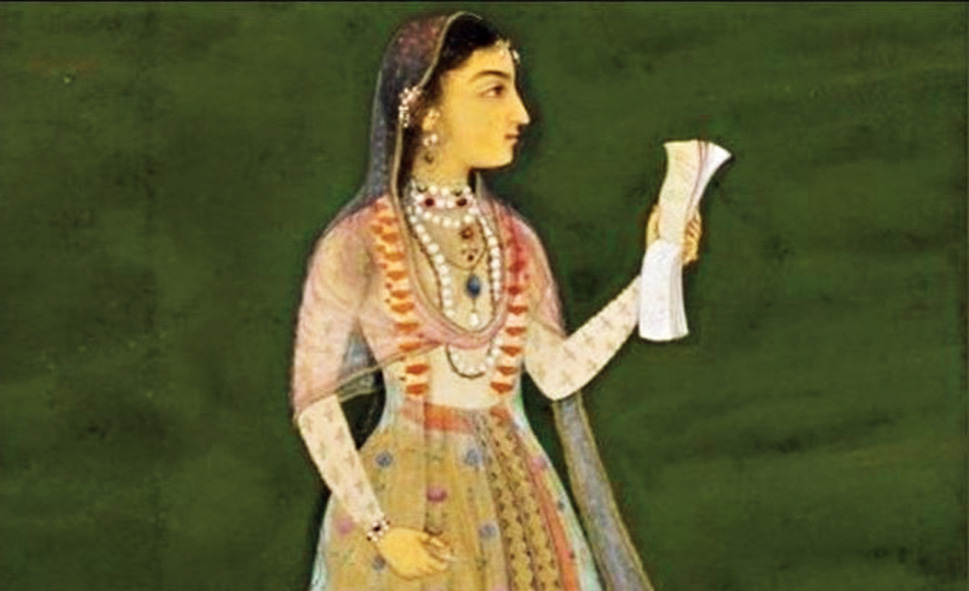

Shah Jahan’s daughter Jahanara Begum had written two books — one of which is her own Sufi journey, how she evolved as a Sufi princess. They always wrote in Persian because that was the official court language.

What inspired you to write your first book Heroines: Powerful Indian Women of Myth and History?

I have two daughters and when they were young I was looking for books to read out to them. They were reading a lot of work that came from England or America, so I was thinking let’s find some local examples as well, people they can have as role models. And all the women I found portrayed in popular history or popular narratives, were sort of these homogenised bland women.

Over the years, even Draupadi had lost her dark colour and she was played by this fair woman. So I was like, ‘What is happening? Let’s go back to the sources and see these women in all their diversity, in all their humanity and their vulnerability.’

So according to you, what does heroism mean for women?

It is mostly if you become like a goddess or if you die in a battle like Rani Lakshmi Bai, even now… like the posters of Manikarnika only showed her as this warrior. We forget that for one-and-a-half years she was communicating with the British, she was doing diplomacy, she was using a translator, she was using an Australian advocate to fight her case against the British. Begum Hazrat Mahal, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s wife, did the same thing in Lucknow… she carried on the rebellion in 1857. She has been forgotten completely because she lived, she went to Nepal and kept trying to fight for her rights there and then died in obscurity. So there are very narrow definitions of heroism in women.

Which character in this book do you relate to the most?

I actually love Gulbadan Begum very much, the woman who wrote this biography. She lived to be a very old woman… she was Babur’s daughter, she saw Humayun’s reign and she died late during Akbar’s reign. She saw three Padshahs and what was remarkable about her was the fact that she was fiercely independent. She went for an all-women Haj in 1575 when she was quite elderly and she was the leader of that party! She took seven years to come back to court and imagine in those seven years, what fun and adventures she must have had.

What attracts you to history to write all your books about it?

I find history is poorly served in India. If you consider someone

like a Rani of Jhansi, her exact equivalent would be somebody like Joan of Arc. Joan of Arc has some 10,000 books written about her, in French and in English. In India, there are a handful of books on Rani Lakshmi Bai.

How difficult is it to write about history that needs to always be factually correct?

People are rewriting history in all sorts of ways as you know, which is why it’s all the more important to have scholars like Ruby Lal, people like myself, who are driven by the desire to have this very solidly researched. I spent 50 per cent of my time in research and 50 per cent in writing. It was as important for me to do that research and to find the facts that are absolutely correct, but you have to interpret them and put them together in a way that engages people. For Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire, I researched for one-and-a-half to two years and then writing it took another year.

What kind of books did you read as a child?

I think I read the regular books that were available at that time, the Enid Blyton and all. Then I grew up and much later thought that we have this sense of nostalgia in us, the English speaking readers, for things like cucumber sandwiches, tomato sandwiches, daffodils in the breeze... I thought this is not our lived experience, then why am I nostalgic for something I’ve never lived? I wanted my kids to have an alternative to that, which is grounded in Indian reality — with mangoes, peacocks, the harsh sun — a different reality.

You studied natural science and now you write about history. How did this shift happen?

I started as a scientist and it has been a crazy journey! I try and use it as an example for people, that women’s destiny... you think you’ll go a certain direction and then things happen — be it for family, parents, children. When you’re given that chance, it’s very important to seize it. I had this opportunity and I was ready for it with full speed (laughs).

So, what’s next?

A biography on Akbar... It should come out by next year but I’m not telling anyone the name of the book because I’m superstitious (laughs).