Banpur might only be 110 kilometres northeast of Calcutta, in Nadia district, but it is a borderland. The railway station there stands less than a kilometre from the India-Bangladesh border. It is nearly afternoon by the time we — writer Manjira Saha and myself — reach Gate No. 32, a checkpost. Manjira, a local schoolteacher, has been researching how the barbed fence along the border means much more than a geo-political boundary, how it also defines the lives and sensibilities of the people inhabiting the borderland. She has written three books in Bengali about border lives, including Chhotoder Border last July, which is about what children living on the border make of it.

Just as our cycle van approaches the checkpost, an official of the Border Security Force (BSF) approaches us. “How far is Bangladesh,” I ask him. The strapping man in uniform points eastwards and says, “There.” He seems casual enough and yet something makes me think he senses that we are not casual tourists.

Manjira tells me how she got interested in the lives of children in borderlands. She says, “At first, when I started work at the school here, I would be shocked when my students spoke about things like smuggling across the border, trafficking of cows and human beings alike. For them, the India side is epith or this side and Bangladesh is opith or the other side. A 10-year-old would casually recount how he had thrown a pack of cigarettes or cosmetics across the fence and earned himself money enough for a soft drink or a bar of chocolate.” She explains why it took her a while to understand that most of them considered murders, custodial deaths and disappearances of a close relative or an acquaintance as part of life.

At 12 noon, Gate No. 32 swings open — it also opens once in the morning and once in the evening, each time for an hour. Those who live in the no man’s land or on the strip of land located 150 yards beyond the zero line along the India-Bangladesh border, use this window to return home. (Zero line or the Radcliffe Line is the international boundary drawn between India and Bangladesh.) Kulopara, across Gate No. 29, is one such village.

There are 339 other villages in six districts of Bengal with a population of 70,000 people, where the barbed fence came up following an international border agreement — the joint India-Bangladesh guidelines of 1975. According to it, a free zone with no inhabitants would be created 150 yards from the zero line on either side. India accepted the condition, but not Bangladesh. Unlike India, it did not create any fencing because most people on that side refused to give up their land. As a result, today thousands of people with blurred nationalities live here.

That day, we look on as Gate No. 32 swings open and lets out a steady trickle of men, women and children on either side. Regular folks carrying nylon bags, bales of jute, sacks of grain, plastic containers tied on to cycles. There are farmers and farmhands with sickles and tiffin carriers. They deposit their photo IDs with the BSF jawans before they go any further. BSF staff check each person for contraband items. The women are hustled to closed rooms by women security guards.

Manjira spots a former student in the crowd. She tells me the 16-year-old was supposed to appear for her Class X exams but dropped out the last minute. Manjira calls out to her. “Madam, we don’t stay on this side anymore,” replies Asmatara Khatun. Turns out that after her father disappeared — he was most likely killed in a scuffle while smuggling goods across the border — her mother married a farmhand from the other side.

Manjira asks Asmatara, “By opith, you mean Bangladesh? Or the buffer zone?”

She thinks and then replies, “I don’t know. Beyond the barbed wire, there are pillars with numbers on them. We presume the Roman numerals indicate India, and Bengali numerals indicate Bangladesh. It is confusing.” Asmatara is on this side today to visit her maternal uncle’s wife, who is ailing. She assures her former teacher that she has joined a madrasah and is continuing with her studies, and so saying takes our leave.

Watching her disappearing form, Manjira says, “Here you see people cross the checkpost but there are porous points people cross at nights. Not all are criminals.”

The border between India and Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan, was hastily drawn by British lawyer Sir Cyril Radcliffe in the summer of 1947. He had been commissioned to do so based on the religious demography of the region. While drawing the fence on paper, his line cut through human lives alienating farmlands from homesteads and markets from produce. For years, the border remained porous, with people crossing the line to go to weekly markets, visit relatives, arrange marriages and attend village fairs.

Aloke Sinha Roy, a 61-year-old resident of Banpur, tells things as they were. He says: “I remember watching football matches in which clubs from both sides of the border would participate.” According to him, up until the early 1960s, at the time of the annual jatra or the annual fair at the dargah of Pir Malek Gaus, thousands would gather at Matiari adjoining Banpur. “Those days, the border meant just a few stones,” he adds.

Things started to change apparently after the India-Pakistan war in 1965. India created the BSF to patrol the frontiers of the country with the primary focus on preventing unauthorised entries and exits, and checking trans-border crimes. The strict vigil disrupted the fundamentals of an agrarian community, criminalising customary transactions. Smuggling across the border since then has become a viable business. “Men, women and even children took to ‘black’, the local term for smuggling,” says Sinha Roy.

It might be simplistic to blame the tradition of smuggling across the border on vigil alone. But after Bangladesh was born in 1971, the smuggling network expanded.

Says Tarak Das, a 30-year-old rickshaw-puller, “We grew up watching raids on homes and listening to gunshots.” By then, the business of smuggling had assumed new dimensions; cows, women, weapons and even explosives were trafficked from one side to another.

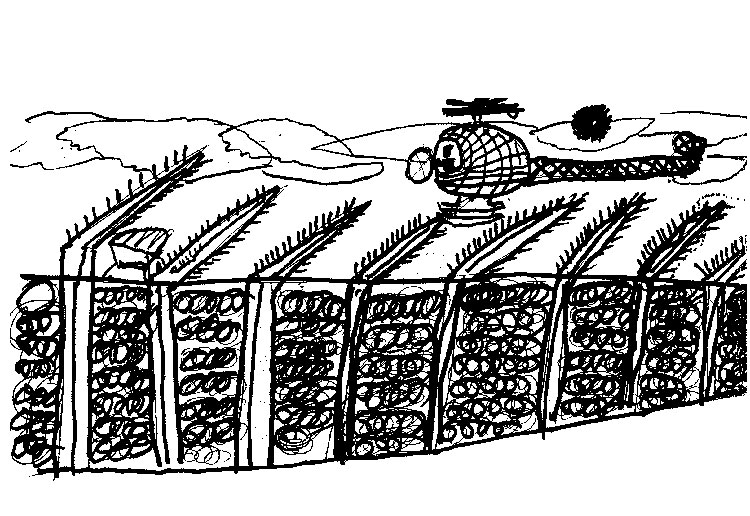

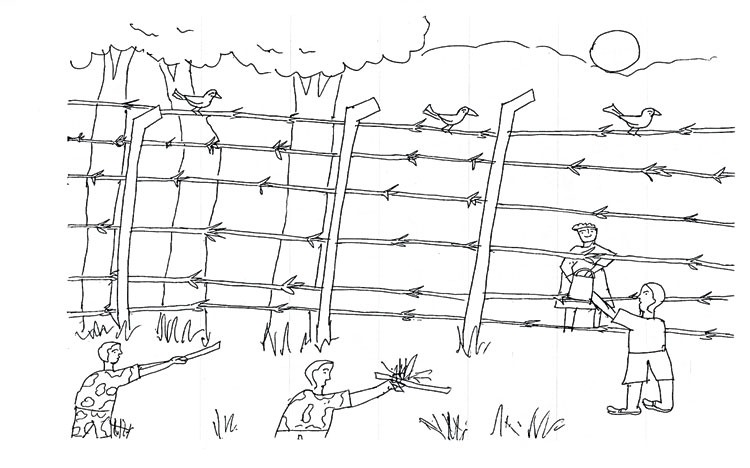

A drawing by a Class V student Source: The book, Chhotoder Border

Chhotoder Border is a collection of children’s writings on the border, as well as visual representations. There is page after page of line drawings — Manjira had organised a drawing competition for children of the village and asked them to draw the border and caption them. All the drawings have the barbed wire fencing in common — loops, straight lines, stars on straight lines. Of course, depending on the child’s locatedness with respect to the border and consequent relationship with it, perspectives vary. Some represent it as a neat line at a distance, one or two will have trees towering over it, in other drawings the fencing is all-consuming. It did not occur to most of these children to represent human beings, unless they were drawing the BSF jawans.

The writings are a tad conscious, as would be when asked to address a specific topic. There seems to be a general effort to highlight the good things about the border — some children mention the beautiful trees adjoining it, the “very good police uncles” patrolling it, some have written, “We love our border”. But what comes through also and more tellingly are the other details of life on the border.

A student of Class V writes how she has seen things being smuggled across the border. “Maal pass” is the term she uses and it appears again and again in the writings of the younger children as well as those from high school, as do the references to the BSF personnel.

Manjira says when she took up the job at the school in 2009, barbed wire fences had already come up. The fencing had been there in places since 1994. But in 1999, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) assumed power and put speed on it. As it turned out, instead of working as a deterrent, the fence became a challenge people on either side learnt to negotiate and live with.

She recalls an experience from her early days. She was taking an early morning local train to work, when she noticed a frail woman sitting by a window. Says Manjira, “She seemed pregnant. At some point I looked to my side and there, in the mellow morning light, I saw another pregnant woman. As I consciously scanned the compartment, every other woman seemed to be pregnant. I was shaken. It felt like a strange dream or something out of a movie.” When she discussed the experience with some senior students, they told her as they giggled at her naiveté, that those women were smugglers and the baby bumps contained contraband items.

I eventually meet some of the children who featured in Manjira’s research project. They talk about the smuggling and other criminal activities, which they seem to have normalised. Two girls tell me how they have spotted smugglers passing caged birds, porcupines and even a horse. One of them draws for me the special type of ladder used to smuggle cows and humans.

“Sir,” says a 13-year-old boy, “last week, security guards seized three kilos of gold biscuits packed in a vegetable basket”. Another interjects, “He doesn’t know anything. The gold weighed four-and-a-half kilos. I live just beside the checkpost and I can see everything.”