As I walk down the long corridor that leads to the office of Sarmistha De, assistant archivist at the Directorate of State Archives, in north Calcutta, I notice piles of hardbound files. The pages peeping out from them are yellowed and, as is obvious to the eye, brittle with time. “It is from such files that we have dug up the history of the colonisation of the Northeast,” says De.

“A history that found no mention in our school texts,” Simonti Sen, director of the State Archives had told the gathered audience on the day of the launch of the book titled North East (1830-1873): Select Documents Part I.

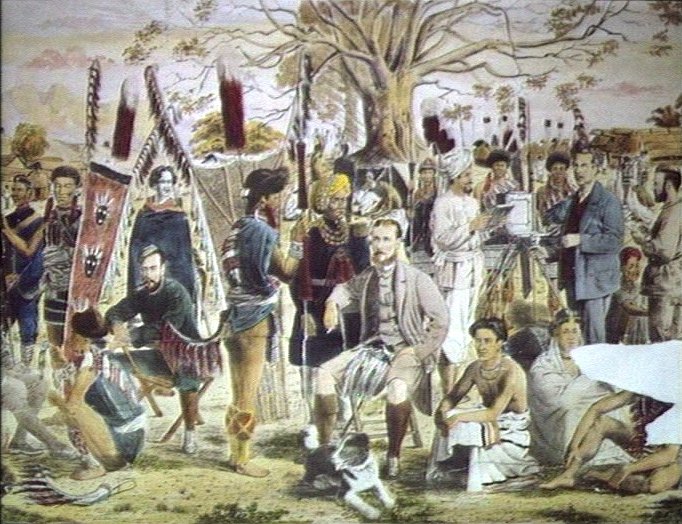

De and her colleague, Bidisha Chakraborty, have worked on the book. And the dry title notwithstanding, it is teeming with tales of the East India Company’s foray into the Northeast in the mid-nineteenth century. How its officials went about it, the way they negotiated with the ways of the tribes, how they studied them and manipulated them. All of it pieced together from government department registers, government correspondence, inter-departmental memos.

The Company was lured by the natural resources of the geography— coal, tea, oil. Says De, “At first, there was only Assam and Manipur. The documents trace the history of formation of Nagaland and show how the Company penetrated the mountainous terrain for revenue collection.”

But first, they got rid of the Burmese presence in the region. They waged the Anglo-Burmese wars and gained control over Assam and Manipur. Next, they deposed the king of Assam. Points out De, “Beginning 1826, they started controlling everything — the relationship between the royal families, the relationship of the king with the local population, the movement of the kings, even relationships within royal families.”

Chakraborty shows me a letter from the queen of Manipur to the Company complaining that her husband had not fulfilled his marriage contract and stating her own poor financial condition. In another letter from 1836, King Purandhar Singh seeks permission from the Company to mint coins in his own name on the occasion of some royal ritual. He repeatedly assures them that there is no other intention behind his request.

Not only did the Company regulate the activities of the king, it also became the chief determinant of the politics of the region. “By the treaty of 1833, the British government acceded to the king of Manipur the region lying between Jiri and the western bank of Barak rivers. The condition was that Chanderpur held by the Raja should be handed over to Cachar,” says De. The book comes with old maps showing this region and that region.

Neither De nor Chakraborty are willing to take credit for the idea of producing the book. It seems, Raghavendra Singh, currently the secretary of the Union ministry for culture, first floated the concept. At the time Singh was director of National Archives of India and he wanted to hold an exhibition on the Northeast. But when that didn’t happen, all that research took the shape of the book.

Back to the book’s innards. Annotations on the sides of an 1872 map of the Garo region read thus: The deep olive green and yellow lines N. & S. denote the boundary as now laid down between the Khasias and the Garos.

The maps mirror how closely and intensively the British engaged with the region, if only to control it, exploit its people. One of the first things they did was try and gain control over the region by collecting revenues from the tribes. And where they could not gain control by negotiating, they used coercive measures. There are documents to show how the British levied fines on the Garo villages for any act of insubordination. One such reads: “From the year 1817 to 1832, no less than 37 Garrow (sic) villages were fined to the extent of 8,000 rupees.”

Often these actions led to skirmishes. There is a memorandum dated October 1862 from a brigadier-general St. G.D. Showers to the secretary to the Government of Bengal for the information of the lieutenant governor. It goes: “I have the honor to report that on the 30th a Guard of ten men of the 44th Native Infantry escorting the Dak from Dingling were attacked by the rebels... A few days ago two armed Rebels were seized in the jungle overlooking Jowai; they said they had been sent to examine and report on the strength of the Guard there...”

Not that the Company was any less nosy. There is a receipt from 1871, sent from one H. LePoer Wynne, undersecretary to the Government of India, foreign department, to one Rivers Thompson, officiating secretary to the Government of Bengal, Judicial Department. It acknowledges and discusses how a sum of Rs 25,000 was given to a Mr Edgar — to procure intelligence and offer presents to Lushais — appears “unnecessarily large for the purpose”.

But the Nagas were no pushovers. De says that there are documents upon documents that show that the British could not gain control over the war-like Nagas. Nothing worked — neither befriending Nagas with subsidies nor the policy of negotiation with the chief of the clans.

Chakraborty shows me a handwritten document from 1840. The header reads: Fort William, the 14th July, 1840. And thereafter, follows list upon list of Naga tribes inhabiting specific geographies — identified here as those living between the Booree Dehing and Desang rivers or between the Desang and Deko rivers and so on and so forth. The names of the different Naga tribes run thus: Dauduniya, Soobang, Nuogaya, Namsungeya, Poolaong, Burdwariya... “It is commendable how the British had penned every detail, their devious intentions notwithstanding,” says De.

The colonial officials emphatically recorded the absence of any definite ideas of religion among the Nagas. In official records, the entry of American Baptist Mission in this region was justified as a way of making them “more civilised and religious”.

Chakraborty tells me that the next book will be about the development work done by the British in the region. How they worked towards the urbanisation of Guwahati, how they opened up educational institutions, organised health camps and appointed Garos as vaccinators.

The school texts may be unyielding yet, they may not open their pages to all or part of these old new revelations, but this research will definitely go towards filling some of the blanks in some of our minds.