The narration is chronologically simple, but the writing has an eloquence spilling over into verbosity. The author affects a Kiplingesque, archaic prose, and English colloquialisms find a place beside literal translations of Indian expressions, with, say, “guttersnipe” existing alongside “good-bad words”. Is there no other way to create the atmosphere of the colonial era? The gloss provided for “jamadar” needs to be looked at. The saying about the Dutts of Lahore, “na Hindu na Musalmana”, certainly does not bear the same import as “adha Hindu adha Musalman”. In “[m]aza le le rasiya nayi jhulni ka”, jhulni is not the swing but the nose-ring, which doubles the innuendo. The nose-ring is both an object and a metaphor of much consequence in a bai’s life, making this change of meaning a noticeable oversight.

The author’s effort to portray an artist’s interaction with her music is commendable. But how does the reader differentiate between historical fiction and heavily fictionalized history? This book situates itself within that same anecdotal historicity that it draws its material from.

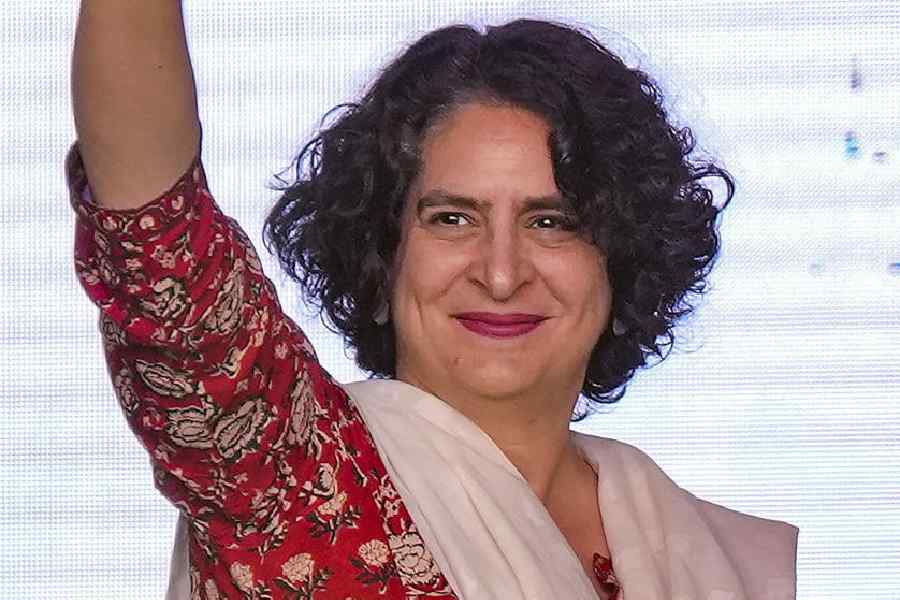

Requiem in Raga Janki By Neelum Saran Gour, Viking, Rs 599

Author Neelum Saran Gour's latest novel displays her deep acquaintance with Allahabad Image: http://www.neelumsarangour.com

Neelum Saran Gour’s Requiem in Raga Janki is a book that feels light for its size, and the same can be said of the novel. Structured like a remembrance of the titular character by an old courtesan, the novel loses its act after a few chapters and seems to consider imagination to be the same as complete creative licence.

Saran Gour seems to be deeply acquainted with Allahabad and its surroundings, and deploys her knowledge to recreate the people and the environment of the then United Provinces. Yet the historical backdrop and the buzzing social unrest get a lesser treatment. The narrative also does not bring up the rise of the new trade-based aristocracy, with a changed attitude towards entertainment, especially music and its patronage. The milieu created is more about the old aristocracy still ensconced in its illusion of superiority; an artist rising above her circumstances despite her gender, and the popular anecdotes of the world of Hindustani classical music, from Tansen to Gauhar Jaan.

Bai Janki Bai Ilahabadi (1880-1934) lived in the heyday of the gramophone era. The recording companies’ money-making endeavour, along with their feigned interest in Indian music is a fascinating phenomenon. Equally fascinating is the contrast between the caginess of the male singers who hoarded their musical knowledge, and the women who came forward to share and disseminate their equally rich repertoire. Yet the book engages neither topic in much detail. Perhaps the stylized speeches by Ustad Hassu Khan Sahib could have been used as an element to touch upon these issues.

In an interview with the Sunday Guardian, the author said, “I was drawn to the shadowy rumour that her name has sunk to.” Rescuing Janki Bai from oblivion seems to have turned her into the larger-than-life protagonist of a fictionalized biography that still manages to lapse into a generic bai’s life. But the characters around Janki — Manki, Naseeban, Akbar Ilahabadi, Haq Sahib, even Mahesh Chand in the last pages, and Raghunandan and his chhappan-chhuri act in the first few — keep it as grounded as possible, while lending a much-needed diversity to the unvaried trajectory.