THE COOKING OF BOOKS: A LITERARY MEMOIR

By Ramachandra Guha

Juggernaut, Rs 699

Imagine a hostel corridor in the early years of the 1970s. A lanky boy in his late teens is quietly waiting for his turn to be initiated into a cult of semi-academic rituals. Another lanky young man, probably bearded and slightly older than the other boy, emerges out of the shadows and beckons him. They enter a room and the older male starts playing records of Western classical music; the younger man has to name the compositions. If the junior gets some of them right, the senior will treat him to tea or some other stronger liquid. If he fails, his intellectual dreams may forever be shattered.

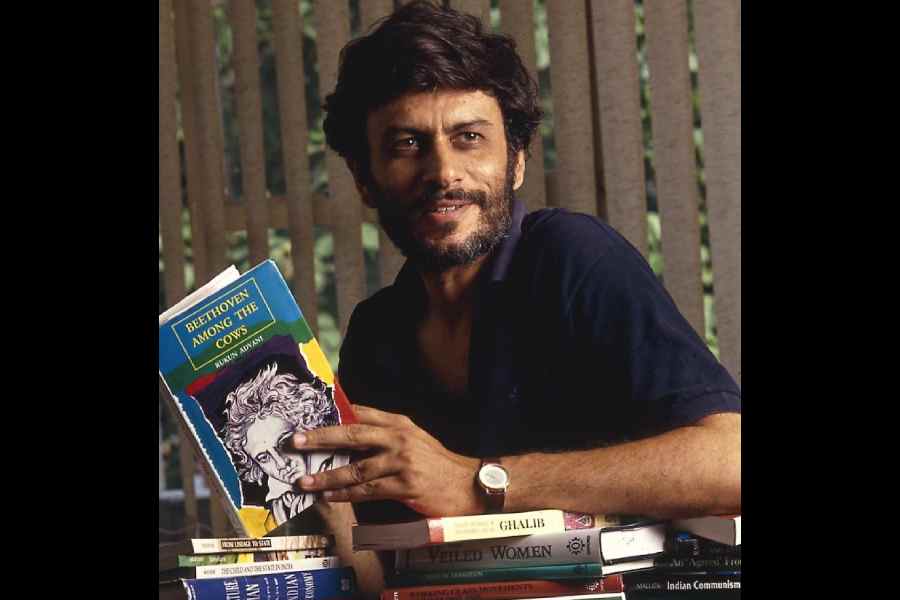

I know that you are already frowning. Isn’t this some sort of ragging, albeit with an air of controlled sophistication and extra-curricular charisma? Maybe. The bigger question, though, is if one can distinguish it from the horrors that draw blood from one’s birth identity, social capital and class location in some of the best institutions in the country. It is indeed very difficult to draw a line. The act of initiation that the passage above describes can only lead to a happy ending of camaraderie over chai if the one being initiated has already had some exposure to the world of elite intellectualism. Ramachandra Guha’s latest book — probably his shortest and definitely his most intimate — opens with this act of initiation. The initiated would later become the famous novelist, Amitav Ghosh. The initiator has chosen to remain in the shadows most of his life — Guha’s protagonist and friend, Rukun Advani.

Living in the shadows does not mean that he is an obscure figure. Advani was an editor (and later the head of academic publishing) with the Oxford University Press, India. He handled the publication of the prestigious Subaltern Studies series and became instrumental in shaping Guha’s own career as a historian of India after Independence. Advani, Ghosh and Guha went to the same college — St. Stephen’s College in Delhi — in the Seventies, although for Guha Advani remained a distant presence in their college days. Guha used to be a sportsperson at the time, harbouring the ambition of playing Test cricket for India. The book offers a fascinating account of how a boy from Dehradun who seldom attended his lectures in college became one of the most celebrated public intellectuals of the country. His voluminous works on environmental and postcolonial histories and popular writings on cricket opened up new avenues of research and inspired generations of students to take up themes, which rarely got attention from mainstream academia.

Guha acknowledges his debt to Advani for this transition in a caring prose that draws upon the nostalgia for a simpler, more tolerant, yet creatively exciting time. By extensively quoting from his correspondence with Advani, he prepares a narrative that works as a character study as well as a series of personal reflections about the world that they both inhabited — a world of freethinking and excellent copy-editing. There are implicit hints that this world was also fraught with imbalances of power, although Guha does not seem too interested in exploring the structural inequalities that were essential in giving this realm the charm.

Ironically, Guha’s own story is the biggest reminder of these inequalities. Even after coming from the same posh school attended by the likes of Amitav Ghosh, he was denied entry to the network of intellectual Brahmins. He had to fight for his own niche and the academic world did not embrace him with open arms as it should have. Advani was one of the few people who recognised his potential and continued to offer him book contracts and editorial guidance.

It is, however, another matter that this system works if — and only if — benevolent people like Advani are at the helm of the ship. It is no news that the publishing world in India is still a ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial’ (to borrow from a theoretical framework from Guha’s youth) space where a chance encounter with a college senior at a party might present one with opportunities that would never be available to those who did not go to that college. This reviewer, who did go to one such college, thoroughly enjoyed the book. But he does not know whether an ‘outsider’ will share his views.