Empress of The East: How a Slave Girl Became Queen of the Ottoman Empire By Leslie Pierce, Icon, £20

It would be underestimating Empress of the East to consider it merely a biography of Roxelana (circa 1502-1558), the slave girl from Ruthenia — then ruled by Poland and now a part of Ukraine — who became Hurrem Sultan, queen of the superpower of that age, the Ottoman empire. She managed to have five more children with Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (1494- 1566) after having borne him a son, making him almost monogamous; she even married the sultan in 1534, rising to the status of queen from that of a concubine. This was unprecedented! She died aware of the fact — reassuring to her — that one of her sons would be the next sultan, thanks to her political manoeuvring. The book not only gives us a detailed account of the world and the times she lived in, but almost transports us there.

There have been female monarchs and premiers of state, who have all been written about extensively and rightly so. A good biographical dictionary of such women is Claudia Gold’s Women Who Ruled: History’s 50 Most Remarkable Women (2015). Along with them there have also been women who reigned as de facto rulers, even if not de jure, but they have not received the attention they deserved. A corrective to it, and a much-needed one, can be seen in the advent of a few recent publications, such as Ira Mukhoty’s Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire (2018) and Ruby Lal’s Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan (2018). Nur Jahan (1577-1645) was born nineteen years after Roxelana’s death, and came to enjoy as much power in the Mughal empire as Roxelana did in the Ottoman. Lately, women who have broken the glass ceiling and ruled in different domains of life, such as business, media, and sport, and not just politics, have also grabbed attention. An example is Rebecca Stanborough’s 25 Women Who Ruled (2018).

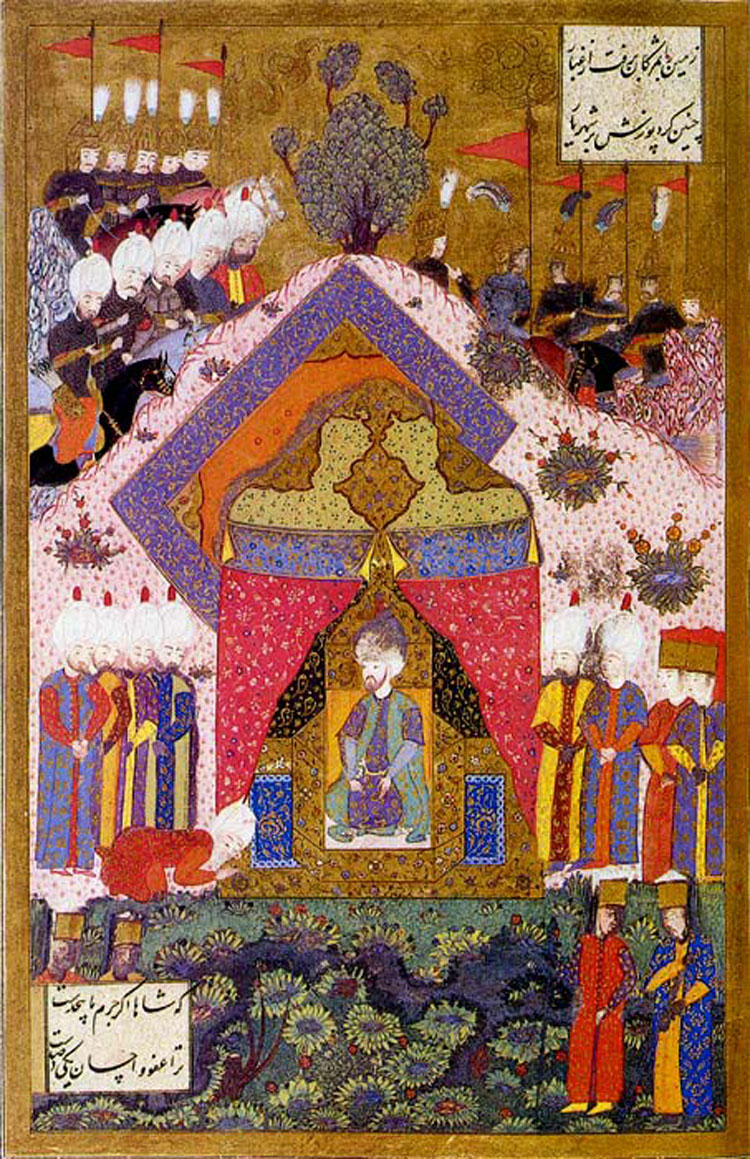

Although the present book, which has a huge canvas, falls in the league of those mentioned above, it stands out. This is because through the story of just one individual, although most extraordinary, it touches upon a range of subjects and issues, namely, slavery, concubinage, eunuchs, religious conversion, fratricide, status of religious minorities in the Ottoman empire, women’s chastity through seclusion, social norms around sex, and many more. It gives us a peep into the world of the Ottomans, whose ethnic origin lay in the same geographical region as that of all dynasties that ruled India during the Sultanate period (1206-1526) — except the Lodis (1451-1526) and the Suris (1540-1555). The region was north of the River Oxus (Amu Darya), known as Turkistan then, and occupied today by the Commonwealth of Independent States, a loose federation of Muslim majority states that seceded from the Soviet Union. The Mughals (1526-1857 with the interlude of 1540-1555), too, traced their origin from the same region. The Shahi Imam of the Jama Masjid of Delhi suffixes Bokhari to his name even today, indicating his roots in Bokhara in the region mentioned above. The erstwhile princely state of Hyderabad came to have strong matrimonial ties with the Ottomans and concern for the continuity of the Ottoman rule (1280-1924) even triggered a whole campaign in India — the Khilafat Movement (1919-1922).

Peirce gives us a profile of the international nature of both the Ottoman harem and the administration. Ranks of both were filled with Christians from the Balkans, Circassia, Anatolia, and Slavic lands, who had been forcibly converted to Islam. For her in-depth study of the Ottomans, their State, society and harem, she relies on a variety of primary sources in a number of languages, ranging from the correspondence between Roxelana and Suleiman, to the accounts left by Venetian ambassadors and other European envoys, to travelogues and memoirs.

Pointing out the etymological origin of the term harem, Peirce explains how “its usage over time conveyed two general and clearly related meanings: a space that is forbidden or unlawful, and a space that has been declared sacred, inviolable, or taboo. A harem was a zone in which certain individuals or certain forms of conduct were forbidden — in other words a kind of sanctuary.” It is noteworthy that the most revered spaces in the 16th century Ottoman empire came to be known as harems — “the interior of a mosque, the Muslim sacred compound in Jerusalem, and, above all, the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina,” as Peirce tells us. According to her, the fact that the Ottomans “characterized the zone surrounding the sultan as a harem reminds us of how they understood and assessed power — that one moved inward toward it, not upward.” This inference becomes all the more significant given the fact that Muslim ruling dynasties across the world tried to imitate the Ottomans, both in harem and court. The book is immensely rewarding for those interested in the Ottoman world.