Book: Urdu Crime Fiction: 1890-1950 — An Informal History

Author: C. M. Naim

Published by: Orient Blackswan

Price: Rs 875

How old is crime fiction and what is crime fiction? The answer to both questions can be somewhat subjective. From the author’s Preface — “A ‘mystery,’ for me, is a tale of detection, a narrative in which a crime occurs, surrounded by mystery, which is then resolved, always near the end, by the book’s hero, usually a private detective or a police officer. A ‘thriller,’ on the other hand, is a narrative which may begin with some mysterious or gruesome incident but soon loses much of that air of mystery, becoming instead a tussle of wits and strength between the criminal and the hero.”

The difference is, of course, not watertight. Modern crime fiction in English (and other European languages too), crime fiction defined as ‘mystery’, dates back to the 19th century. Exposure to Western literature and education and the advent of the printing press meant that Indian languages would also discover crime fiction, initially as translations or transcreations, and, subsequently, as originals. Bengal has a treasure trove of authors and detectives, starting with Panchkari Dey and Priyanath Mukhopadhyay. A few years ago (in 2004), Francesca Orsini wrote an essay on detective novels in 19th-century North India. (It was published in a collection of essays on India’s literary history.) A simple point made in the essay was that different Indian languages discovered and reinvented crime fiction at different paces. Bengal’s obsession with detective fiction is more than most, and it continues. At best, it may have metamorphosed from the written word to films and television. In the Epilogue, C.M. Naim writes, “As my work progressed, one surprising fact slowly crystallized: the total absence of female crime fiction writers in Urdu.”

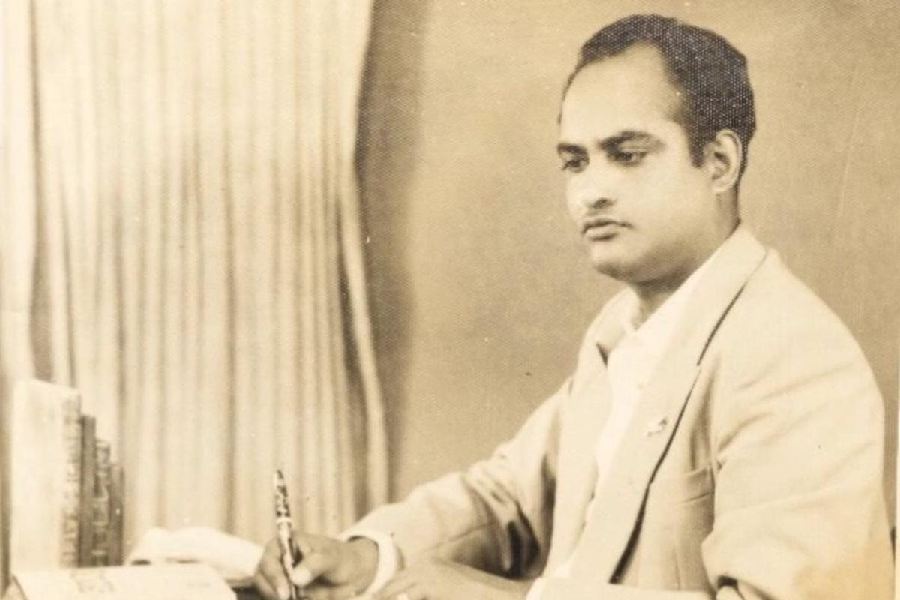

There is no denying a gender bias. But in Bengali, there are Leela Majumdar, Prabhabati Devi and Suchitra Bhattacharya, not to speak of women detectives. It is fair to say Urdu crime fiction was slower off the post, not only compared to Bengali but also Hindi. Therefore, unless you are an aficionado, you don’t hear much about it. Naim’s book is almost certainly a first and involves a considerable amount of detection too. The year, 1890, is roughly when crime fiction arrived in Urdu. (The 1950 marker is more complicated.) The survey of literature, with detailed listings in the appendices, reads like a PhD dissertation. One shouldn’t form the impression all crime fiction is fancy. There is the cottage industry type too. (In school, I also remember gorging on Swapan Kumar and his detective, Dipak Chatterjee.) Not having read Urdu crime fiction (except the gist in this book), I wonder — (a) is the cut-off date of 1950 appropriate? Ibne Safi’s phenomenal writing career seems to have occurred later. Since Urdu took to crime fiction later, its tapering off also probably happened later, after 1950. (b) What about Urdu crime fiction written and published in Pakistan? (Ibne Safi migrated there in 1955.)

This engrossing book (with twelve chapters) is, therefore, probably a partial picture of Urdu crime fiction, both in time and space. But very well written.