Book: BASU CHATTERJI: AND MIDDLE-OF-THE-ROAD CINEMA

Author: Anirudha Bhattacharjee

Published by: Vintage

Price: ₹699

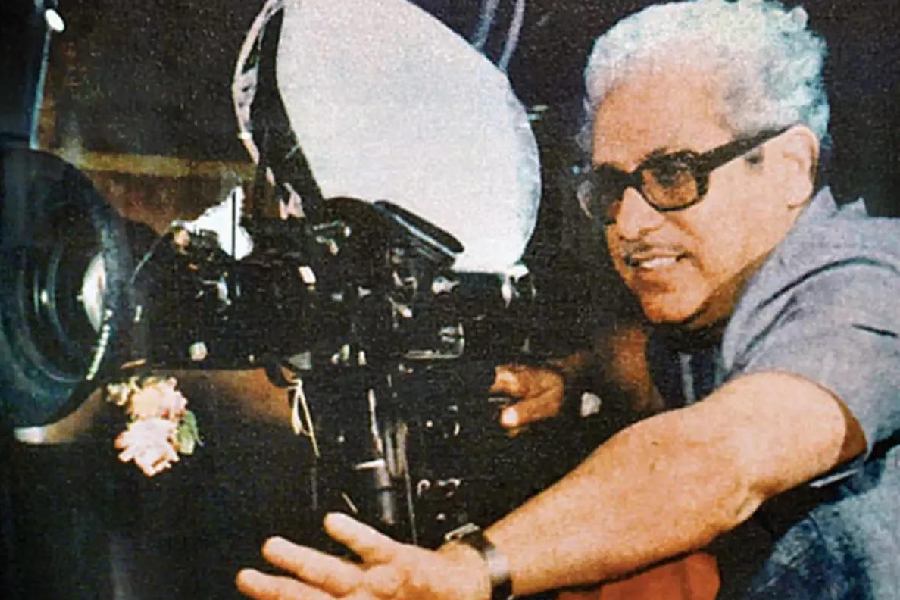

The stillness of the rural and the restlessness of the urban, the roots of a past and the branches of a new nation, the frenzy of city lights and the rhythm of the rain — these dualities shaped middle-of-the-road cinema in India for about three decades starting from the 1950s. Anirudha Bhattacharjee’s book presents its readers with what comprised “Middle-of-the-Road” films in the vast panorama of Indian cinema. Bhattacharjee narrates episodes from Basu Chatterji’s life as a film-maker in the form of a tapestry stitched through chronicles, interviews and memoirs. This chronicle, when placed within the history of an emerging modernity in India, offers a layered understanding of the simplicity that lies at the heart of Chatterji’s films.

Since the 1950s, Indian cinema had been trying to bolster the image of a capable alpha male synonymous with an Independent India. Amitabh Bachchan skyrocketed into popularity with his exemplary construction of “the angry young man”. Alongside, Indian cinema witnessed a burgeoning rise of “masala” movies that catered to Bollywood’s promise of entertainment. The anecdotes in Bhattacharjee’s book show how Chatterji relentlessly explored a new ground in his films and how his artistic pursuit was nourished by a different kind of sensitivity.

On one hand, the book piques readers’ interest by describing the uniqueness of Chatterji’s plots and, on the other, by unpacking the process of making those films through interviews and anecdotes. Most of Chatterji’s films dealt with an inner conflict in the characters — in Sara Akash, the protagonist is torn between what he wants to be and what society expects from him; in Rajnigandha, the woman is torn between two cities — Mumbai and Delhi — that also signify her ex-lover and her simple boyfriend in the present; Chitchor is a love triangle; Piya Ka Ghar tells the story of a couple who seek privacy within their cluttered everydayness of a chawl in Mumbai.

The book also points at how Chatterji’s works have been radical at multiple levels. He built his stories around independent women characters who could choose, desire and even fall in love with more than one man. Most of his stories were based on the struggles and the triumphs of a new middle-class. Chatterji’s cinematic canvas was filled with people gravitating from cities to villages and also the other way round, which was symptomatic of the mobility in the modern landscape of India.

Bhattacharjee has divided the book into three sections that span a chronological timeline. The rich political and historical context of the turbulent years after Independence and the formation of art institutes and archives during the 1960s and 1970s demanded more critical attention in the narrative. Anecdotes on casting in Chatterji’s films weigh heavier than any other aspect in the book.

Basu Chatterji: and Middle-of-the-Road Cinema has scattered references to certain innovations that Chatterji introduced to Indian cinema that have often passed unnoticed — such as his use of collage and how the camera follows the characters, his adaptation of the literariness of the stories into the visual language of films, his use of zoom, of an opening song in the title track to lay out the canvas, of a hand-held camera to shoot the rhythm of cities and rain, his nonchalant declaration of Sara Akash as “an offbeat art film”. The book successfully drives home the idea of how a hybrid modernity in India found articulation in Chatterji’s films.